‘Reade him, therefore; and againe, and againe’. It’s the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s First Folio, a monumental project put together by his friends

- Written by David McInnis, Associate Professor of Shakespeare and Early Modern Drama, The University of Melbourne

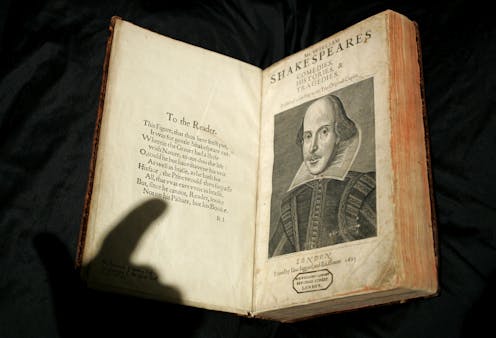

Shakespeare’s First Folio – more accurately known as Mr William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies – was published 400 years ago this November.

It is the book that gave us Martin Droeshout’s famous engraved portrait of Shakespeare, and playwright Ben Jonson’s equally famous praise describing him as “not of an age, but for all time”. It remains one of the most iconic and recognisable books in English, with copies sometimes selling for around US$10 million[1].

The folio contains 36 Shakespeare plays – 18 of which had never been published before – along with two poems by Jonson that have significantly shaped Shakespeare’s reputation.

The first published collection of Shakespeare’s plays, it was put together by his fellow actors John Heminge and Henry Condell, seven years after Shakespeare’s death. Plays published here for the first time included Macbeth, The Taming of the Shrew, Antony and Cleopatra, Coriolanus, The Tempest, Twelfth Night, Julius Caesar and As You Like It.

Despite the hefty price tag, the folio is not a rare book. Of the conjectured 750 copies printed, hundreds still survive. A popular estimate is 235 extant copies, though the Shakespeare Census project[2] more specifically lists the locations of 228 substantively complete copies and a further 155 fragments (that is, copies with fewer than half their original leaves).

Of these, a staggering 82 copies were collected by the American businessman Henry Folger and his wife Emily in the early 20th century. These are held by the library they built for this purpose as a gift to the public – the Folger Shakespeare Library – in Washington, DC.

Meisei University in Japan holds 12 copies, and around 20 copies remain in private hands. “New” copies turn up regularly, if not frequently: in 2006, 2014, and twice in 2016, for example. Oxford’s Bodleian Library discarded its copy of the First Folio sometime in the 17th century, but in 1905 it was promptly snapped up again by its original owner![3]

So if it’s not a rare book, what makes a First Folio so special? The way the book was presented provides some clues.

Read more: Guide to the classics: Shakespeare’s sonnets — an honest account of love and a surprising portal to the man himself[4]

‘What ever you do, Buy’

Heminge and Condell composed two prefatory notes that frame the book rather differently.

In the first – the dedication to two of Shakespeare’s patrons, William Herbert, Earl of Pembroke and Philip Herbert, Earl of Montgomery – Heminge and Condell refer humbly to Shakespeare’s plays as “trifles”. They urge the dedicatees to patronise the plays as they patronised their author, likening the plays to “Orphanes” in need of “Guardians”.

The pair are at pains to emphasise the lowly quality of their offering, likening the plays to the “leavened Cake” offered to the gods of many nations “that had not gummes & incense”. Seen thus, with the implication that the plays will be made precious through this offering to the earls, the folio cements Shakespeare’s reputation by virtue of endorsement by its patrons.

In their second address, Heminge and Condell invoke the commercial imperative, urging people to “read and censure” the book of plays if they will, but to “buy it first”. “What ever you do, Buy”.

They style themselves as collectors and gatherers of Shakespeare’s plays: they assembled the works and brought the plays together for the first time. And of course, as one would expect of a sales pitch, they dismiss earlier publications as “stolne, and surreptitious copies, maimed, and deformed”.

By contrast, the folio they assembled offers plays “cur’d, and perfect of their limbes, and all the rest, absolute in their numbers, as he conceived them”. (Subsequent scholarship has demonstrated how false such claims often were; the quality of the versions of the plays in the folio is far from uniform.) Here, it’s the publishing industry that seemingly secures Shakespeare’s posthumous reputation.

Common to both epistles is the notion that the reader will have experienced the plays previously – on stage or in allegedly inferior published form – and that the folio marks a turning point.

The plays presented here are to be read and understood in the context of Shakespeare’s career:

Reade him, therefore; and againe, and againe: And if then you doe not like him, surely you are in some manifest danger, not to understand him.

Such sentiments remind me of the biting comment Ben Jonson makes in Every Man Out of His Humour (1599): “Art hath an enemy called Ignorance”.

A shift in thinking

It’s worth noting that the folio imposes the classical five-act structure onto plays that were generally conceived with only scenes in mind.

Between around 1590, when the public amphitheatre venues in London really took off, and 1608, when Shakespeare’s company began performing in the indoors Blackfriars playhouse (in addition to its outdoor Globe playhouse), English commercial plays didn’t typically use a five-act structure. (With its regular Choruses, Henry V – and to a lesser extent Romeo and Juliet – is exceptional in the Shakespeare canon in this regard.)

The generation of “university wits” who dominated the 1580s theatrical scene had all been raised on classical drama and therefore emulated its style. But Shakespeare did not go to university as far as we know, and it wasn’t until his company began performing at an indoor playhouse, where candles needed to be trimmed at regular intervals during performance, that it began to deliberately include act breaks.

The folio editors, however, attempt to impose them on Shakespeare’s plays, so they look more like the classical drama that was deemed worthy of serious consideration.

Read more: We've found a Shakespeare folio but a swag of original plays are still missing[5]

By the time of his death in 1616, around half of Shakespeare’s plays had appeared in print in single-text editions, typically in quarto format. (The term “quarto” refers to a sheet of paper being folded twice to produce four “leaves” – that is, eight pages – of a book; a “folio” results from folding the sheet just once, to yield two leaves and thus four pages.)

Modern fans of Shakespeare can be surprised by which plays were published and reprinted in this way, and which plays were not: Titus Andronicus appeared in quarto three times, Richard II five times, and Pericles three times before Shakespeare died. Othello, Macbeth, and Antony and Cleopatra did not appear in print during the author’s lifetime.

Scholars have argued about what inherent quality made a play like Titus appeal to stationers as a sound publishing investment. We still don’t entirely know how such decisions were made, but the folio represents a shift in thinking: rather than speculating about an individual play’s worthiness or otherwise for print, the priority was gathering Shakespeare’s plays together.

A play like Timon of Athens that not only hadn’t appeared by itself in quarto, but wasn’t even originally planned for inclusion in the folio, could eventually find a home in the volume because it was contributing to the greater project, and the reasons for printing it were independent of any perceived commercial value it may have held on its own.

Lost forever? Perhaps not

A piece of received wisdom about the folio that most cling to is probably not true: it’s unlikely that unpublished masterpieces such as The Tempest, Twelfth Night and Julius Caesar would have been lost forever had they not been published in 1623.

The fact that copies of these plays were still available to the folio editors seven years after Shakespeare’s death and ten years after his retirement from the stage suggests that they were still accessible or even in use.

Presumably, like The Two Noble Kinsmen, a collaboration between Shakespeare and John Fletcher that came out in quarto in 1634, many or even all of these 18 plays would have eventually found their way into the world in standalone quartos or as augmentations to subsequent folios.

Fortunately we don’t have to wonder “what if”, because the folio did bring together 36 of Shakespeare’s plays in a single volume, the sum greater than the parts. Only two Shakespeare plays that didn’t appear in the First Folio (Love’s Labour’s Won[6] and the Fletcher collaboration, Cardenio[7]) are known to have been lost.

Literally a monumental project, the folio’s appeals to patronage and commerce, combined with its praise of the playwright’s wit, formed a multi-pronged approach to ensuring Shakespeare’s genius would receive the appreciation his friends thought it deserved.

400 years later, we continue to appreciate Heminge and Condell’s labours.

References

- ^ US$10 million (www.smithsonianmag.com)

- ^ Shakespeare Census project (shakespearecensus.org)

- ^ promptly snapped up again by its original owner! (treasures.bodleian.ox.ac.uk)

- ^ Guide to the classics: Shakespeare’s sonnets — an honest account of love and a surprising portal to the man himself (theconversation.com)

- ^ We've found a Shakespeare folio but a swag of original plays are still missing (theconversation.com)

- ^ Love’s Labour’s Won (lostplays.folger.edu)

- ^ Cardenio (lostplays.folger.edu)