How the new relaxed Olympic rules make Brisbane’s 2032 bid affordable

- Written by Judith Mair, Associate Professor, The University of Queensland

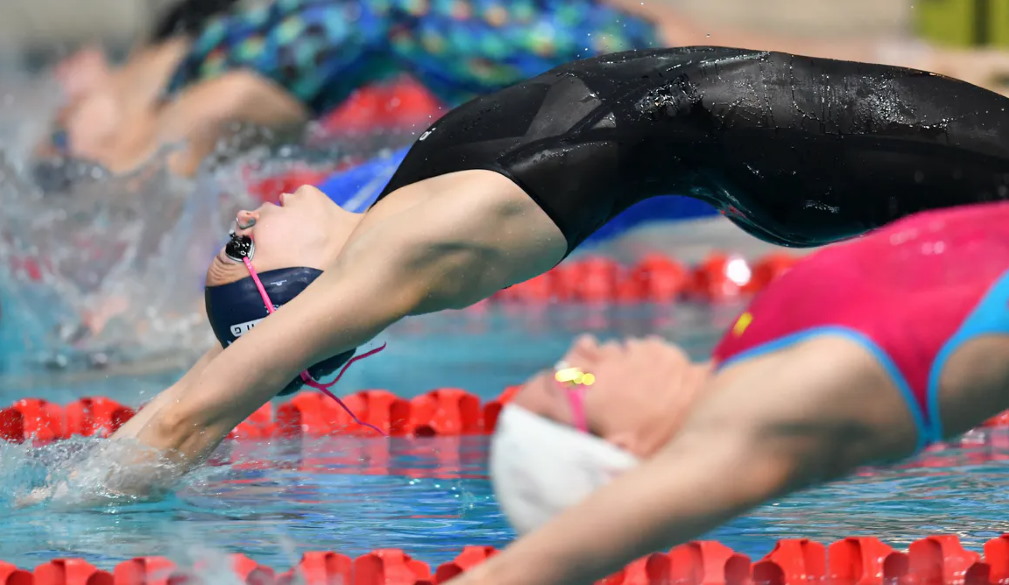

Brisbane is in pole position to win the rights to stage the Olympic and Paralympic Games in 2032, after being named as the preferred candidate city[1] last month. The excitement is building, but the hard economic realities of staging a mega-event can’t be ignored.

Previous Olympic and Paralympic Games have mixed legacies. There have been stories of venues lying abandoned[2] and host cities left with crippling debts that have taken years to pay off[3]. So will things be different for Brisbane?

The International Olympic Committee (IOC) is well aware of the risks for host cities. In 2018, it introduced the “New Norm”[4] for candidate cities bidding to host the Olympics from 2024 onwards, with 118 reforms to “re-imagine” how they deliver the event.

The key takeaway is the need to cut costs and risks for host cities by introducing more flexibility and efficiency[5]. The aim of the New Norm is to produce a more sustainable legacy for host cities. But how will it work in practice?

Reduce, re-use and recycle

An example of how the New Norm will reduce costs is the relaxation of the IOC demand that each sport/sporting federation needs its own venue. From now on, venues can be used for multiple sports. This means less new infrastructure is needed.

Read more: Breakdancing in the Olympics? The Games have a long history of taking chances, from pesapallo (yes, it's a sport) to kite flying[6]

Another example is the idea that athletes will be able to fly in, compete in their events, then fly home. In previous Games, athletes were accommodated for the full duration of the Games.

This means we will be able to construct a smaller athletes’ village with multiple occupancies over the Games period. The village will become commercial/retail premises following the Olympics.

The IOC will now allow the use of temporary venues for the Olympics. Previously, everything was purpose-built. Now we will be able to construct venues that can be dismantled after the event, or temporarily adapt existing venues. This will keep the costs of building new venues to a minimum.

The economic implications

The New Norm means the costs of staging Olympic and Paralympic Games have been substantially reduced. But there is still big cash involved.

Australian Olympic Committee (AOC) president John Coates has said[7] the operational budget for the 2032 Games will be A$4.5 billion.

Queensland Premier Annastacia Palaszczuk (left) and AOC President John Coates (right) speak about the bid to host the 2032 Olympics in Brisbane. Darren England/AAP

Queensland Premier Annastacia Palaszczuk (left) and AOC President John Coates (right) speak about the bid to host the 2032 Olympics in Brisbane. Darren England/AAP

Coates is also optimistic the Games will be delivered as near to cost-neutral as possible. He said[8]:

[O]n a budget of A$4.5 billion, the IOC is putting in $2.5 billion […] then you get approximately $1 billion from national sponsorship and $1 billion from the ticketing.

That’s enough then to pay for both the Olympics and Paralympic Games without any call on the state, or federal or local governments.

But it is not strictly accurate to say the Games will end up costing Brisbane nothing. “Operating costs” for the Olympic and Paralympic Games basically means the cost of putting on the event. Nothing more, nothing less.

To be ready for the event, both the state and federal governments will need to invest significant sums in building venues and the athletes’ village and upgrading roads and public transport. These are capital costs, which will be taxpayer money along with private investment.

The tourism sweetener

So what might be the lasting benefits of hosting the Olympics that make it a cost worth bearing?

Based on studies[9] of previous Olympics, three significant positive outcomes are worth highlighting.

Firstly, Brisbane and Queensland will be in the global limelight – we couldn’t afford to pay for that kind of publicity. This global attention is likely to result in increased tourism, trade and investment.

The UK government says there were record-breaking figures for tourism and spending in London during the 2012 Olympic Games. UK Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport/Flickr, CC BY-NC[10][11]

The UK government says there were record-breaking figures for tourism and spending in London during the 2012 Olympic Games. UK Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport/Flickr, CC BY-NC[10][11]

In London, more than 800,000 international visitors attended a 2012 Olympic event, delivering a boost of almost £600 million[12] “excluding ticket sales”.

While tourism is almost certain to increase in the short term following the event, evidence[13] for long-term increases in tourism after hosting a mega-event is mixed.

Secondly, there are many intangible benefits to the residents of host cities, including increased civic pride and social cohesion as well as community health and well-being benefits.

Thirdly, it can be argued that hosting a mega-event like this can be the catalyst to bring forward many improvements in public transport, roads and services that might otherwise have taken decades to deliver.

Not everyone stands to benefit

Although there should be an ongoing positive legacy from new roads and sporting infrastructure, there will be opportunity costs – maybe a school extension that gets delayed, or a new hospital that gets postponed.

Read more: Celebrate ’88: the World Expo reshaped Brisbane because no one wanted the party to end[14]

Also, it is very likely any positive social impacts will not be dispersed equally. Those living in rural and regional Queensland and in already disadvantaged or marginalised communities might not see how the Games help them at all.

The IOC’s New Norm has allowed Brisbane to bid to host the Olympics at a much lower cost than previous host cities have had to bear. But we need to make sure that hosting the Games maximises the potential benefits and minimises the impacts of the negatives.

It’s important that more than just Brisbane benefits from bringing the Olympics to Queensland. bpaties/Flickr, CC BY[15][16]

It’s important that more than just Brisbane benefits from bringing the Olympics to Queensland. bpaties/Flickr, CC BY[15][16]References

- ^ preferred candidate city (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ lying abandoned (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ pay off (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ “New Norm” (www.olympic.org)

- ^ flexibility and efficiency (stillmed.olympic.org)

- ^ Breakdancing in the Olympics? The Games have a long history of taking chances, from pesapallo (yes, it's a sport) to kite flying (theconversation.com)

- ^ said (www.abc.net.au)

- ^ said (www.abc.net.au)

- ^ Social impacts of mega-events: a systematic narrative review and research agenda (espace.library.uq.edu.au)

- ^ UK Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport/Flickr (www.flickr.com)

- ^ CC BY-NC (creativecommons.org)

- ^ almost £600 million (assets.publishing.service.gov.uk)

- ^ Social impacts of mega-events: a systematic narrative review and research agenda (espace.library.uq.edu.au)

- ^ Celebrate ’88: the World Expo reshaped Brisbane because no one wanted the party to end (theconversation.com)

- ^ bpaties/Flickr (www.flickr.com)

- ^ CC BY (creativecommons.org)

Authors: Judith Mair, Associate Professor, The University of Queensland