Is it actually false, or do you just disagree? Why Twitter’s user-driven experiment to tackle misinformation is complicated

- Written by Eryn Newman, Senior Lecturer, Research School of Psychology, Australian National University

Over the past year, we’ve seen how dramatically misinformation can impact the lives of people, communities and entire countries.

Read more: Public protest or selfish ratbaggery? Why free speech doesn't give you the right to endanger other people's health[1]

In a bid to better understand how misinformation spreads online, Twitter has started an experimental trial in Australia, the United States and South Korea, allowing users to flag content they deem misleading.

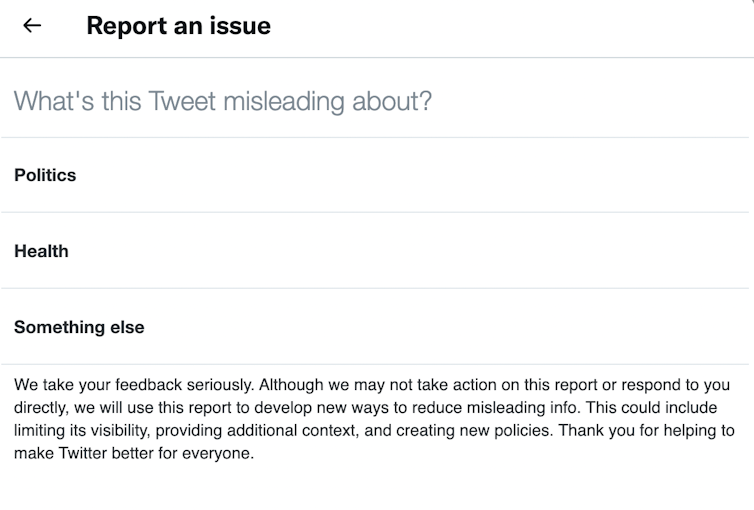

Users in these countries can now flag tweets as misinformation through the same process by which other harmful content is reported. When reporting a post there is an option to choose “it’s misleading” — which can then be further categorised as related to “politics”, “health” or “something else”.

According to[2] Twitter, the platform won’t necessarily follow up on all flagged tweets, but will use the information to learn about misinformation trends.

Past research has suggested such “crowdsourced” approaches to reducing misinformation may be promising[3] in highlighting untrustworthy sources online. That said, the usefulness of Twitter’s experiment will depend on the accuracy of users’ reports.

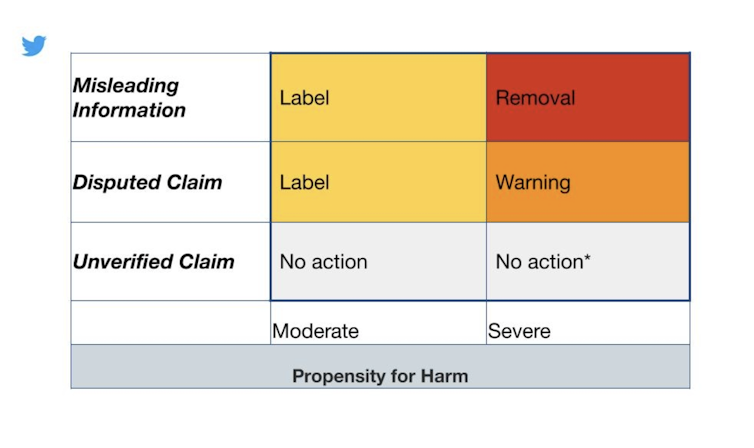

Twitter’s general policy describes a somewhat nuanced approach[4] to moderating dubious posts, distinguishing between “unverified information”, “disputed claims” and “misleading claims”. A post’s “propensity for harm” determines whether it is flagged with a label or a warning, or is removed entirely.

In a 2020 blog post, Twitter said it categorised false or misleading content into three broad categories.

Screenshot

In a 2020 blog post, Twitter said it categorised false or misleading content into three broad categories.

Screenshot

But the platform has not explicitly defined “misinformation” for users who will engage in the trial. So how will they know whether something is indeed “misinformation”? And what will stop users from flagging content they simply disagree with?

Familiar information feels right

As individuals, what we consider to be “true” and “reliable” can be driven by subtle cognitive biases. The more you hear certain information repeated, the more familiar it will feel. In turn, this feeling of familiarity tends to be taken as a sign of truth.

Even “deep thinkers” aren’t immune[5] to this cognitive bias. As such, repeated exposure to certain ideas may get in the way of our ability to detect misleading content. Even if an idea is misleading, if it’s familiar enough it may still pass the test[6].

In direct contrast, content that is unfamiliar or difficult to process — but highly valid — may be incorrectly flagged as misinformation.

The social dilemma

Another challenge is a social one. Repeated exposure to information can also convey a social consensus, wherein our own attitudes and behaviours are shaped by what others think[7].

Group identity[8] influences what information we think is factual. We think something is more “true” when it’s associated with our own group and comes from an in-group member (as opposed to an out-group member).

Research[9] has also shown we are inclined to look for evidence that supports our existing beliefs. This raises questions about the efficacy of Twitter’s user-led experiment. Will users who participate really be capturing false information, or simply reporting content that goes against their beliefs?

More strategically, there are social and political actors who deliberately try to downplay certain views of the world. Twitter’s misinformation experiment could be abused by well-resourced and motivated identity entrepreneurs[10].

Twitter has added an option to report ‘misleading’ content for users in the US, Australia and South Korea.

Screenshot

Twitter has added an option to report ‘misleading’ content for users in the US, Australia and South Korea.

Screenshot

How to take a more balanced approach

So how can users increase their chances of effectively detecting misinformation? One way is to take a consumer-minded approach. When we make purchases as consumers, we often compare products. We should do this with information, too.

“Searching laterally[11]”, or comparing different sources of information, helps us better discern[12] what is true or false. This is the kind of approach a fact-checker would take, and it’s often more effective than sticking with a single source of information.

At the supermarket we often look beyond the packaging and read a product’s ingredients to make sure we buy what’s best for us. Similarly, there are many new and interesting ways[13] to learn about disinformation tactics intended to mislead us online.

One example is Bad News[14], a free online game and media literacy tool which researchers found could “confer psychological resistance against common online misinformation strategies”.

There is also evidence that people who think of themselves as concerned citizens with civic duties[15] are more likely to weigh evidence in a balanced way. In an online setting, this kind of mindset may leave people better placed to identify and flag misinformation.

Read more: Vaccine selfies may seem trivial, but they show people doing their civic duty — and probably encourage others too[16]

Leaving the hard work to others

We know from research that thinking about accuracy[17] or the possible presence of misinformation in a space can reduce some of our cognitive biases. So actively thinking about accuracy when engaging online is a good thing. But what happens when I know someone else is onto it?

The behavioural sciences and game theory tell us people may be less inclined to make an effort themselves if they feel like they can free-ride[18] on the effort of others. Even armchair activism may be reduced if there is a view misinformation is being solved.

Worse still, this belief may lead people to trust information more easily. In Twitter’s case, the misinformation-flagging initiative may lead some users to think any content they come across is likely true.

Much to learn from these data

As countries engage in vaccine rollouts, misinformation poses a significant threat to public health. Beyond the pandemic, misinformation about climate change[19] and political issues continues to present concerns for the health of our environment and our democracies.

Despite the many factors that influence how individuals identify misleading information, there is still much to be learned from how large groups come to identify what seems misleading.

Such data, if made available in some capacity, have great potential to benefit the science of misinformation. And combined with moderation and objective fact-checking approaches, it might even help the platform mitigate the spread of misinformation.

References

- ^ Public protest or selfish ratbaggery? Why free speech doesn't give you the right to endanger other people's health (theconversation.com)

- ^ According to (www.theverge.com)

- ^ may be promising (www.pnas.org)

- ^ approach (blog.twitter.com)

- ^ aren’t immune (www.sciencedirect.com)

- ^ it may still pass the test (behavioralpolicy.org)

- ^ what others think (onlinelibrary.wiley.com)

- ^ Group identity (www.sciencedirect.com)

- ^ Research (journals.sagepub.com)

- ^ identity entrepreneurs (www.icrc.org)

- ^ Searching laterally (cor.stanford.edu)

- ^ better discern (link.springer.com)

- ^ interesting ways (misinforeview.hks.harvard.edu)

- ^ Bad News (www.getbadnews.com)

- ^ concerned citizens with civic duties (psycnet.apa.org)

- ^ Vaccine selfies may seem trivial, but they show people doing their civic duty — and probably encourage others too (theconversation.com)

- ^ thinking about accuracy (www.sciencedirect.com)

- ^ free-ride (www.britannica.com)

- ^ about climate change (theconversation.com)