How lab-grown hybrid lifeforms bamboozle scientific ethics

- Written by Julian Koplin, Lecturer in Bioethics, Monash University & Honorary fellow, Melbourne Law School, Monash University

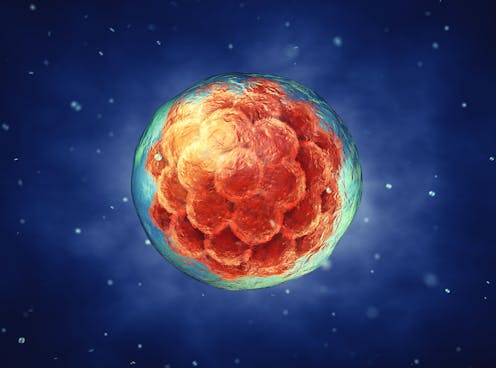

Earlier this month, scientists at the Guangzhou Institutes of Biomedicine and Health announced[1] they had successfully grown “humanised” kidneys inside pig embryos.

The scientists genetically altered the embryos to remove their ability to grow a kidney, then injected them with human stem cells. The embryos were then implanted into a sow and allowed to develop for up to 28 days.

The resulting embryos were made up mostly of pig cells (although some human cells were found throughout their bodies, including in the brain). However, the embryonic kidneys were largely human.

This breakthrough suggests it may soon be possible to generate human organs inside part-human “chimeric” animals. Such animals could be used for medical research or to grow organs for transplant, which could save many human lives.

But the research is ethically fraught. We might want to do things to these creatures we would never do to a human, like kill them for body parts. The problem is, these chimeric pigs aren’t just pigs – they are also partly human.

If a human–pig chimera were brought to term, should we treat it like a pig, like a human, or like something else altogether?

Maybe this question seems too easy. But what about the idea[2] of creating monkeys with humanised brains?

Chimeras are only one challenge among many

Other areas of stem cell science raise similarly difficult questions.

In June, scientists created “synthetic embryos[3]” – lab-grown embryo models that closely resemble normal human embryos. Despite the similarities, they fell outside the scope of legal definitions of a human embryo in the United Kingdom (where the study took place).

Like human–pig chimeras, synthetic embryos straddle two distinct categories: in this case, stem cell model and human embryo. It is not obvious how they should be treated.

In the past decade, we have also seen the development of increasingly sophisticated human cerebral organoids[4] (or “lab-grown mini-brains[5]”).

Unlike synthetic embryos, cerebral organoids don’t mimic the development of a whole person. But they do mimic the development of the part that stores our memories, thinks our thoughts, and makes conscious experience possible.

Most scientists think current “mini-brains” are not conscious[7], but the field is developing rapidly. It is not far-fetched to think a cerebral organoid will one day “wake up”.

Complicating the picture even further are entities that combine human neurons with technology – like DishBrain[8], a biological computer chip made by Cortical Labs in Melbourne.

How should we treat these in vitro brains? Like any other human tissue culture, or like a human person? Or perhaps something in between[9], like a research animal?

A new moral framework

It might be tempting to think we should settle these questions by slotting[10] these[11] entities[12] into one category or another: human or animal, embryo or model, human person or mere human tissue.

This approach would be a mistake. The confusion sparked by chimeras, embryo models, and in vitro brains shows these underlying categories no longer make sense.

Read more: As scientists move closer to making part human, part animal organisms, what are the concerns?[13]

We are creating entities that are neither one thing nor the other. We cannot solve the problem by pretending otherwise.

We would also need good reasons to classify an entity one way or another.

Should we count the proportion of human cells to determine whether a chimera counts as an animal or a human? Or should it matter where the cells are located? What matters more, brain or buttocks? And how can we work this out?

Moral status

Philosophers would say these are questions about “moral status[14]”, and they have spent decades deliberating on what kinds of creatures we have moral duties to, and how strong these duties are. Their work can help us here.

For example, utilitarian philosophers see moral status as a matter of whether a creature has any interests (in which case it has moral status), and how strong those interests are (stronger interests matter more than weaker ones).

On this view, so long as an embryo model or brain organoid lacks consciousness, it will lack moral status. But if it develops interests, we need to take these into account.

Read more: Networks of silver nanowires seem to learn and remember, much like our brains[15]

Similarly, if a chimeric animal develops new cognitive abilities, we need to reconsider our treatment of it. If a neurological chimera comes to care about its life as much as a typical human does, then we should hesitate to kill it just as much as we would hesitate to kill a human.

This is just the beginning of a bigger discussion. There are other accounts of moral status, and other ways of applying them to the entities stem cell scientists are creating.

But thinking about moral status sets us down the right path. It fixes our minds on what is ethically significant, and can begin a conversation we badly need to have.

References

- ^ announced (www.sciencedaily.com)

- ^ the idea (link.springer.com)

- ^ synthetic embryos (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ human cerebral organoids (thebiologist.rsb.org.uk)

- ^ lab-grown mini-brains (www.nature.com)

- ^ Cortical Labs (www.scienceinpublic.com.au)

- ^ conscious (www.cell.com)

- ^ DishBrain (www.monash.edu)

- ^ something in between (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- ^ slotting (www.science.org)

- ^ these (blogs.bmj.com)

- ^ entities (www.nuffieldbioethics.org)

- ^ As scientists move closer to making part human, part animal organisms, what are the concerns? (theconversation.com)

- ^ moral status (plato.stanford.edu)

- ^ Networks of silver nanowires seem to learn and remember, much like our brains (theconversation.com)