a globally unique divider splitting Australia's footy fans

- Written by Hunter Fujak, Lecturer in Sport Management, Deakin University

A particular eccentricity of the Australian sporting landscape is that, culturally, our football codes remain strongly tied to their geographic origins.

Australian rules originates from Melbourne, with the southwestern states as heartlands. The rugby codes made their Australian sporting debut in Sydney, with northeastern states as heartlands.

This phenomenon was dubbed “the Barassi Line[1]” in 1978, describing a cultural dividing line based on football preference proposed to run from Eden, NSW, through Canberra and up to Arnhem Land. The term was first used by historian Ian Turner in his Ron Barassi Memorial Lecture that year.

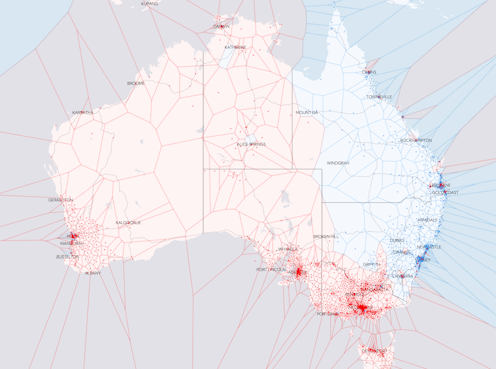

The Barassi Line has been a focus of my research[2] and has recently been plotted and visualised[3] as part of a Wikidata fellowship[4].

In a country that has largely avoided political and cultural hyper-partisanship, the Barassi Line[5] is perhaps our strongest sociogeographic dividing characteristic, and certainly novel in the global context.

Red states and blue states

Where one is raised has a remarkably strong bearing on likely football preferences.

If you walked down the streets of Melbourne, Adelaide, Hobart or Perth, every third person you walked by would be interested in Australian rules and no other football code.

If you entered a Melbourne pub filled with people interested in football (of any variety), 82% of them would AFL supporters[6].

In a similar Sydney sport pub, 73% would support a rugby code[7]. Notably, however, support for the rugby codes varies significantly across Sydney’s geographic subregions[8]. For example, rugby league interest is nearly half as prevalent in North Sydney (28%) as compared to Sutherland (52%).

If you’re Australian, you might be thinking, “Yeah – of course!” But this is not the international norm.

In the United States, for instance, where terrain can range from snow fields to desert landscapes, the variance in popularity between mainstream professional sports leagues is comparatively minimal.

While basketball’s popularity is linked to inner-city urbanisation and baseball retains a rural stronghold[9], Google search volume data[10] nonetheless reveals that 48 of America’s 51 states exhibit an identical hierarchy of sport league popularity (being gridiron, basketball, baseball and ice hockey).

Where is the Barassi Line and how has it changed?

Australian rules authorities have actively attempted to shift the Barassi Line.

As early as 1903, Australian rules administrators began investing in game development, spending more than £10,000[11] on footballs, jumpers, and school coaches to promote the code in Sydney.

In the past decade, the AFL has distributed A$220 million in additional funding[12] to its four northern expansion clubs (the Sydney Swans, GWS Giants, Brisbane Lions and Gold Coast Suns).

Yet despite ever-increasing media coverage and professionalisation, it is remarkable how intact the line remains.

Come 2019, AFL free-to-air telecasts averaged 261,000 Melbourne viewers[13], compared with 21,000 and 23,000 in Sydney and Brisbane, respectively (when not featuring a local team).

Similarly, NRL matches held an average rating in Sydney of about 197,000[14], compared with ratings typically between 5,000 and 20,000 across southern markets.

Mapping the battlefront

Given the Barassi Line represents a metaphorical battlefront, however, real progress is perhaps best measured at the frontline.

Here, the Wikidata fellowship work visualising community football clubs[15] is insightful. This mapping identifies 1,504 Australian rules and 861 rugby league clubs nationally. (Of course, as primarily a creative work, it is possible some clubs were missed in this mapping project). But the distribution of clubs is particularly illuminating, noting:

where Aussie rules was dominant, it was clearly dominant, with league making up just 15% of the two-code-preferred at most in Aussie rules states […] League on the other hand, even when the dominant code, still had a much higher percentage of Aussie rules clubs.

The conclusions outlined in this data visualisation[16] align with those in my book Code Wars[17].

Australian rules is successfully creeping the Barassi Line northward, with the border-straddling region of Murray in NSW aligned with Australian rules.

Significantly, this mapping[18] work suggests Australian rules is also advancing in the adjacent Riverina region.

These regions, while small in population, are of high strategic importance to the football codes because such regional areas produce a disproportionate amount of elite athletes.

Wagga Wagga in the NSW Riverina is known as the “City of Good Sports”. It not only produces a very high number of elite athletes per capita (“the Wagga effect”[19]), but does so across an amazing diversity of sports.

Luminaries include Mark Taylor, Michael Slater, Alex Blackwell, Wayne Carey, Paul Kelly, Peter Sterling, Nathan Sharpe, as well as the Mortimer and Daniher families.

The Barassi Line is hence not just of academic interest, but of vital importance for our football codes in terms of maintaining vibrant junior participation bases. This helps secure the nation’s best future athletes.

The Barassi Line and the broader NSW-Victoria rivalry

A noteworthy feature of the Barassi Line is how it reflects more broadly upon New South Wales and Victoria, which remain fierce cultural, political, and economic rivals more than 120 years after federation.

This was brought into particular focus by political barbing over COVID management[20], but is otherwise most regularly overt in sport[21].

Sporting barbs fuel the state rivalry because Melbourne consciously targeted becoming Australia’s sporting capital in the 1980s. This was a means of economic salvation[22] by diversifying from manufacturing. Sydney, by contrast, positioned itself as the nation’s preferred financial centre[23].

While Melbourne’s sport attendance culture is widely lauded[24], Sydney advocates have previously quipped this reflects the city’s otherwise dullness[25].

Irrespective of our individual sporting preferences, the Barassi Line is something to honour.

It not only puts Australia among the world’s most unique sports cultures. It also explains why we have so many professional football teams and leagues to support.

That Australia’s relatively small population can sustain such an abundance and diversity of football is worth celebrating.

References

- ^ the Barassi Line (en.wikipedia.org)

- ^ my research (search.informit.org)

- ^ plotted and visualised (thepeoplesrepublicofcouch.org)

- ^ Wikidata fellowship (wikimedia.org.au)

- ^ Barassi Line (thepeoplesrepublicofcouch.org)

- ^ 82% of them would AFL supporters (search.informit.org)

- ^ 73% would support a rugby code (search.informit.org)

- ^ varies significantly across Sydney’s geographic subregions (www.tandfonline.com)

- ^ retains a rural stronghold (books.google.com.au)

- ^ Google search volume data (trends.google.com)

- ^ spending more than £10,000 (www.fairplaypublishing.com.au)

- ^ A$220 million in additional funding (www.theage.com.au)

- ^ 261,000 Melbourne viewers (www.footyindustry.com)

- ^ about 197,000 (www.footyindustry.com)

- ^ Wikidata fellowship work visualising community football clubs (thepeoplesrepublicofcouch.org)

- ^ data visualisation (thepeoplesrepublicofcouch.org)

- ^ Code Wars (www.fairplaypublishing.com.au)

- ^ mapping (thepeoplesrepublicofcouch.org)

- ^ “the Wagga effect” (www.waggawaggaaustralia.com.au)

- ^ COVID management (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ sport (www.foxsports.com.au)

- ^ economic salvation (www.utpjournals.press)

- ^ preferred financial centre (www.tandfonline.com)

- ^ widely lauded (theconversation.com)

- ^ dullness (www.cabdirect.org)