Actually, Mr Trump, it's stronger environmental regulation that makes economic winners

- Written by Ou Yang, Research Fellow, University of Melbourne

Donald Trump has ordered US federal agencies to bypass environmental protection laws and fast-track pipeline, highway and other infrastructure projects. Signing the executive order last month, the US president declared[1] regulatory delays would hinder “our economic recovery from the national emergency”.

Trump withdrew the US from the Paris Agreement for international climate action in 2017 for the same reason. The accord, he said[2], would undermine the US economy “and put us at a permanent disadvantage to the other countries of the world”.

Read more: The EPA has backed off enforcement under Trump – here are the numbers[3]

This idea that environmental regulation costs jobs and hurts the economy is deeply entrenched in pro-business discourse. But it is true?

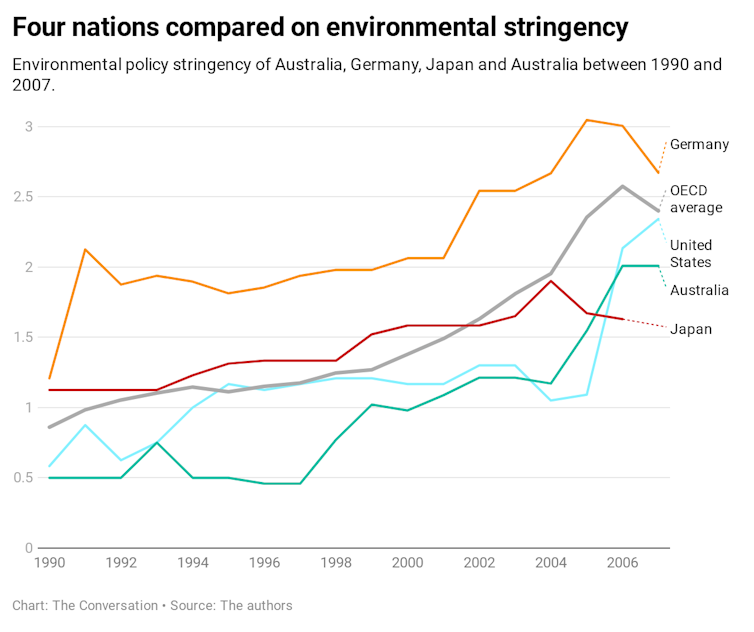

To assess the impact of greater environmental policy on economic productivity we analysed data of 22 member nations of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development[4] (OECD) between 1990 and 2007. Our results show little evidence that environmental “green tape” inhibits economic growth over the long run. The opposite, in fact.

Comparing environmental policy stringency

Past studies of the economic impact of tougher environmental policies have tended to be limited by focusing on immediate effects and looking only at individual nations. Such results are of no help to understand the long-term effects and do not allow for straightforward cross-country comparison either.

This is why we analysed cross-country data stretching over a long period. We used data up to 2007 because that is the most recent year for which the OECD provides free access to all the information we needed for our analysis.

We rated nations’ environmental policies using the OECD’s Environmental Policy Stringency Index[5], developed in 2014. The index calculates a single score based on polices to limit air and water pollution, reduce carbon emissions, promote renewable energy and so on.

Read more: Despite clear skies during the pandemic, greenhouse gas emissions are still rising[6]

All 22 nations improved their stringency scores to varying degrees between 1990 and 2007. The following shows the trajectory of a few example nations – Australia, Germany, Japan and United States against the OECD average. Germany had the second-highest average score over the 17 years. Australia had the worst.

Author provided

We then did complex calculations to measure what effect more stringent environmental policies had on economic productivity – the value of output obtained with one unit of input – both over the short run (one year) and the long run (after three years).

While results for individual nations varied – reflecting local circumstances – overall our results showed a consistent pattern.

In the short run environmental regulations did increase the cost of production. For example, a carbon tax would make coal more expensive, increasing the costs of things like steel production (which uses coal).

But in the long run tighter environmental policies were associated with greater productivity. This positive effect was greater in countries that took the lead on tougher environmental policies. Germany had the highest average economic productivity growth of the 22 nations.

Healthier environment

This positive association might be due to a cleaner environment in the long run increasing the quality of various “production inputs”, such as better health of workers.

For example, a significant 2017 study[7] showed higher exposure to lead (once added to fuel and paint) in childhood was associated with lower intelligence and job status in adulthood. Bans on lead additives in the 1970s have thus contributed to a smarter workforce – a key input for economic growth, as shown by the work of 2018 Nobel economics laureate Paul Romer[8].

Environmental regulations may also prompt industries to focus on efficiency, improving their productivity in the long run.

Author provided

We then did complex calculations to measure what effect more stringent environmental policies had on economic productivity – the value of output obtained with one unit of input – both over the short run (one year) and the long run (after three years).

While results for individual nations varied – reflecting local circumstances – overall our results showed a consistent pattern.

In the short run environmental regulations did increase the cost of production. For example, a carbon tax would make coal more expensive, increasing the costs of things like steel production (which uses coal).

But in the long run tighter environmental policies were associated with greater productivity. This positive effect was greater in countries that took the lead on tougher environmental policies. Germany had the highest average economic productivity growth of the 22 nations.

Healthier environment

This positive association might be due to a cleaner environment in the long run increasing the quality of various “production inputs”, such as better health of workers.

For example, a significant 2017 study[7] showed higher exposure to lead (once added to fuel and paint) in childhood was associated with lower intelligence and job status in adulthood. Bans on lead additives in the 1970s have thus contributed to a smarter workforce – a key input for economic growth, as shown by the work of 2018 Nobel economics laureate Paul Romer[8].

Environmental regulations may also prompt industries to focus on efficiency, improving their productivity in the long run.

US President Donald Trump signs an executive order cutting regulations on May 19 2020.

Kevin/Dietsch

Environmental winners

Our findings suggest stronger environmental protection is compatible with a stronger economy in the long run.

Indeed the evidence is mounting that not taking strong environmental action is likely to have serious economic consequences.

Research suggests, for example, that the continued destruction of natural habitats[9] is making pandemics like COVID-19 more likely, due to pathogens crossing from wild animals to humans.

Read more:

Coronavirus is a wake-up call: our war with the environment is leading to pandemics[10]

Air and water pollution contributes to chemical body burden and disease. Industrialised farming practices have contributed to the loss of about a third of the world’s arable land[11] over the past 40 years.

Then there’s climate change. The consequences of burning fossil fuel are no longer a distant concern. Countries around the world are counting the costs of increased or more catastrophic extreme weather events and other climate impacts.

The countries that show leadership on environmental protection will be the economic winners in the longer run. Those that don’t will be poorer for it in more ways than one.

US President Donald Trump signs an executive order cutting regulations on May 19 2020.

Kevin/Dietsch

Environmental winners

Our findings suggest stronger environmental protection is compatible with a stronger economy in the long run.

Indeed the evidence is mounting that not taking strong environmental action is likely to have serious economic consequences.

Research suggests, for example, that the continued destruction of natural habitats[9] is making pandemics like COVID-19 more likely, due to pathogens crossing from wild animals to humans.

Read more:

Coronavirus is a wake-up call: our war with the environment is leading to pandemics[10]

Air and water pollution contributes to chemical body burden and disease. Industrialised farming practices have contributed to the loss of about a third of the world’s arable land[11] over the past 40 years.

Then there’s climate change. The consequences of burning fossil fuel are no longer a distant concern. Countries around the world are counting the costs of increased or more catastrophic extreme weather events and other climate impacts.

The countries that show leadership on environmental protection will be the economic winners in the longer run. Those that don’t will be poorer for it in more ways than one.

References

- ^ the US president declared (www.whitehouse.gov)

- ^ he said (www.whitehouse.gov)

- ^ The EPA has backed off enforcement under Trump – here are the numbers (theconversation.com)

- ^ Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (www.oecd.org)

- ^ Environmental Policy Stringency Index (stats.oecd.org)

- ^ Despite clear skies during the pandemic, greenhouse gas emissions are still rising (theconversation.com)

- ^ significant 2017 study (today.duke.edu)

- ^ economics laureate Paul Romer (www.nobelprize.org)

- ^ destruction of natural habitats (www.scientificamerican.com)

- ^ Coronavirus is a wake-up call: our war with the environment is leading to pandemics (theconversation.com)

- ^ third of the world’s arable land (www.theguardian.com)

Authors: Ou Yang, Research Fellow, University of Melbourne