We know how to boost productivity and lift wages – but it will take time and much tougher tax reform

- Written by John Hawkins, Senior Lecturer, Canberra School of Politics, Economics and Society, University of Canberra

The slide in Australia’s labour productivity – real gross domestic product per hour worked – has become a real concern. In the past year, labour productivity has fallen 4.6%[1].

Unless it resumes growing, either wage growth will need to slide to the Reserve Bank’s inflation target of 2-3%[2] on average over time, or the bank will need to keep pushing up rates until it does.

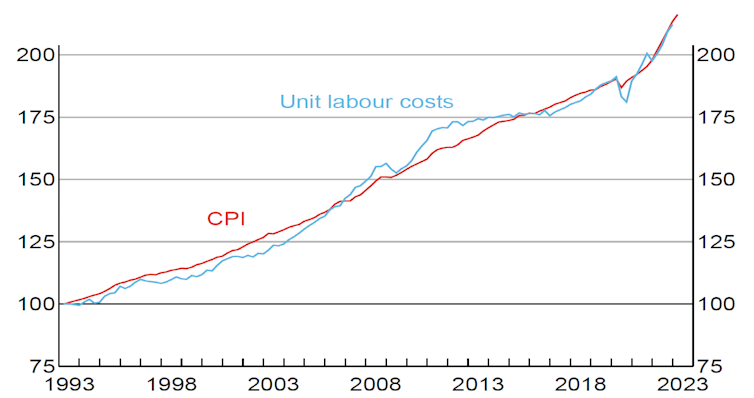

This is because, as Reserve Bank Governor Philip Lowe pointed out in a speech[3] last week, over time increases in the consumer price index move in line with increases in unit labour costs[4] (wage increases divided by increases in labour productivity).

This means that if there is no increase in labour productivity – and right now there isn’t – the consumer price index will come to reflect only wage increases, and the bank will try to bring both down to 2-3%[5], “on average, over time”.

Unit labour costs versus consumer price index

In previous decades labour productivity growth has averaged 2.4% and 2.2%, and most recently 1.1%, allowing wages growth of at least one percentage point above the Reserve Bank’s inflation target without accelerating inflation.

But, for the moment, that no longer seems possible.

Average labour productivity growth the slowest in 60 years

Why productivity growth is sliding

Sliding productivity growth is a worldwide phenomenon. An Australian Productivity Commission report earlier this year found only one[8] advanced economy (Israel) in which average annual productivity growth was higher after 2005 than in the decades before it.

One possible reason for the current decline, suggested by the governor[9], is that during the COVID pandemic, firms concentrated on surviving rather than seeking out more efficient ways to produce.

This is an optimistic suggestion, as it implies productivity growth will rebound.

Another suggestion would be that technology is luring workers into unproductive, time-consuming tasks instead of work.

Many of us spend a good deal of time each day responding to emails (including those from colleagues who insist on annoying “reply all” thank you notes).

A longer-term factor would be that service industries now dominate employment in Australia. Such industries include retail, hospitality and social assistance: areas where there is less room[10] to lift – or even measure – productivity than there was in the industries that used to dominate, such as manufacturing and agriculture.

And while the fall in unemployment to near a 50-year low is good news, it is likely that some of the long-term unemployed now getting jobs are not as productive, at least initially.

Opposition leader Peter Dutton’s proposal[11] to allow unemployed Australians to work more hours before losing benefits would have a similar effect.

Also, the link between productivity growth and wages may run the other way. Falling real wages makes labour cheaper for firms, which might deter them from investing in the equipment needed to boost labour productivity.

As real wages growth fell to long-term lows over the past decade, the share of national income businesses devoted to investment slumped.

Business investment as a share of GDP

In a landmark report[13] in March, the Productivity Commission said it wanted education quality improved and loan eligibility for tertiary students expanded.

And it wanted better-targeted skilled migration and award wages adjusted more fairly and efficiently.

It said the few remaining tariffs on imported goods should be removed and the government’s safeguards mechanism[14] made the primary means of transitioning to net zero greenhouse gas emissions.

It also wanted tax reform, “towards less distortive, more efficient approaches”.

Tax and the Stage 3 cuts in the frame

Views differ on how to reform taxes. We argue reform should be guided by the principle that we should increase taxes on things we want to discourage (such as greenhouse gas emissions and smoking) and lower them on things we want to encourage (such as work and innovation).