The Paralympics strive for inclusion. But some rules unfairly exclude athletes with severe disabilities

- Written by Iain Dutia, Postdoctoral research fellow, The University of Queensland

The Tokyo Paralympic Games, which start today, will feature[1] around 4,400 para athletes competing in 539 medal events across 22 sports.

Among the world’s disability sports organisations, the Paralympic movement has a unique competition framework which permits the pursuit of excellence by athletes who are affected by a wide range of impairments, from relatively mild to severe.

The games are organised and delivered by the International Paralympic Committee (IPC). Its vision is to “make for an inclusive world through sport”, and several recent initiatives demonstrate its global leadership in this area.

Shining examples of this are the IPC’s recent agreement[2] with the World Health Organization promoting diversity and equity in sport and its role in WeThe15[3], a movement devoted to ending discrimination against people with disabilities.

Read more: A brief history of the Paralympic Games: from post-WWII rehabilitation to mega sport event[4]

Equity can be hard to achieve, even for the IPC

However, the work required for governments and sports organisations to make their policies and procedures more inclusive can be complex, exacting and difficult to achieve.

The IPC itself — and the rule used to determine the viability of events on the Paralympic program — are a case in point.

This event viability rule[5] requires that, among other things, individual medal event at the Paralympics must include at least 10 athletes from at least four countries on the world ranking list.

The rule is needed because the number of events on the program can vary from one games to the next. If the number of events needs to be reduced, the rule provides a clear, transparent criterion for determining which ones should be excluded.

Read more: Paralympics haven't decreased barriers to physical activity for most people with disabilities[6]

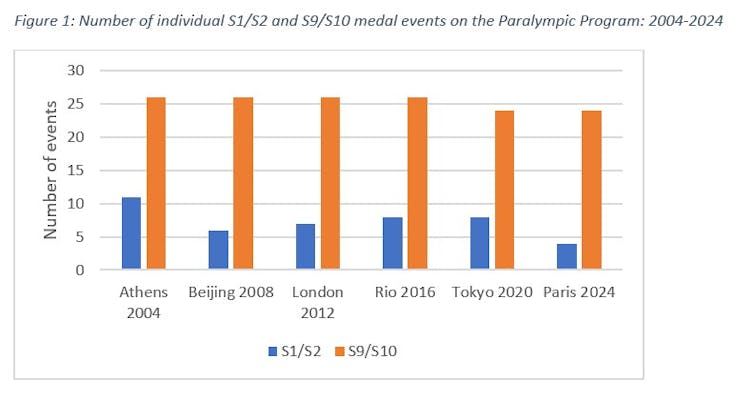

For example, the IPC recently informed national Paralympic committees there would be fewer swimming events at the Paris 2024 Games than in Tokyo. Unfortunately, all the individual events that were removed were for swimmers with the most severe impairments — those in classes S1 and S2 who are affected by conditions such as complete quadriplegia or severe cerebral palsy.

Conversely, no individual medal events were removed for athletes with the least severe disabilities – those in classes S9 and S10 who may, for instance, be missing part of (or an entire) hand.

Greece’s Dimitrios Karypidis competing in the men’s 100m backstroke S1 event in the 2016 Paralympic Games.

ANTONIO LACERDA/EPA

Greece’s Dimitrios Karypidis competing in the men’s 100m backstroke S1 event in the 2016 Paralympic Games.

ANTONIO LACERDA/EPA

How the event viability rule is inequitable

The event viability rule exemplifies the difference between equality and equity[7]. The rule applies equally to all para athletes, but it is not equitable for three main reasons.

First, athletes with more severe impairments face greater barriers to participation in sports than athletes with less severe impairments.

In swimming, for example, an S9/S10 athlete can train with a squad comprising people without disabilities and a coach who requires little specialist disability knowledge. These athletes also do not require facilities with disability access.

Most S1/S2 athletes, however, need individualised sessions with a coach who has considerable specialist disability knowledge and who works in facilities with accessible parking, change rooms and pool entry.

S1/S2 athletes also have complex disabilities and require multidisciplinary medical care in order to participate safely and effectively.

Australian wheelchair racer Fabian Blattman during the 800m T-51 final event at the 2000 Sydney Paralympics.

Wikimedia Commons

Australian wheelchair racer Fabian Blattman during the 800m T-51 final event at the 2000 Sydney Paralympics.

Wikimedia Commons

Second, athletes with severe impairments are not guaranteed the protections afforded by the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities[8] in the same way that athletes with less severe impairments are. This is because Article 30.5 only protects participation in sport by people with disabilities if the required accommodations are deemed to be reasonable.

Unfortunately, many athletes with severe impairments require accommodations — building adjustments and medical expertise — that cannot be reasonably expected of many community sports organisations. Therefore, community organisations can — and do — exclude people with severe impairments, but still meet the requirements of the convention.

Third, compared with athletes with less severe impairments, there are disincentives associated with selecting athletes with severe impairments on national teams.

For example, athletes with severe impairments often require their own personal support staff, accessible accommodation and training facilities, and individualised training and travel arrangements, which makes local and international travel more difficult and expensive.

Read more: Why the 2000 Sydney Paralympics were such a success — and forever changed the games[9]

Fewer events for those with severe impairments

It stands to reason that greater barriers to participation for these athletes reduces the likelihood they will meet the event viability criteria. This is having a significant deleterious effect on their participation in the movement’s flagship event – the Paralympic Games.

As the chart below illustrates, the number of swimming events for S1/S2 athletes has been consistently low for the last 20 years — and it is getting lower.

Author provided, Author provided

There will be no S1 female swimmers at this year’s Tokyo Games. And the Paris 2024 swimming program will have no S1 events at all for the first time since the current classification system was introduced in 1992.

In addition, fewer than 5% of the individual medal events in Paris will be for S2 athletes — all male.

This means a swimmer like Singapore’s Yip Pin Xiu[10] could miss out. Xiu won two golds in S2 swimming events at the 2016 Rio Games and a gold and silver at the 2008 Beijing Games, and is also competing in Tokyo. However, if there are no S2 women’s events in Paris, she might not be able to participate.

By contrast, athletes in the S9/S10 classes will have six times as many events as S1/S2 athletes.

The IPC recognises the unique barriers faced by people with severe impairments who wish to participate in sport. One of its strategic priorities[11] is to increase their participation in para sports across the spectrum. In this respect, the removal of events for these athletes from the Paralympic program is counterproductive.

The legitimacy of the Paralympics depends on inclusion

The IPC’s pursuit of a more inclusive world through sport is an honourable and laudable one. However, in order to be effective, it must start with a rigorous review of its own policies and procedures to make sure that, as an organisation, it is leading by example.

This means reviewing the event viability rule to make it more equitable and reinstating events for athletes with high support needs that were removed from the Paris program.

The IPC should also re-establish the Committee for Athletes with High Support Needs, which is charged with ensuring all sports rules and policies of the IPC are equitable and and inclusive.

This is crucial because, in the long run, the legitimacy of the Paralympic movement depends on not only retaining, but increasing the presence of athletes with severe impairments at the Games.

Author provided, Author provided

There will be no S1 female swimmers at this year’s Tokyo Games. And the Paris 2024 swimming program will have no S1 events at all for the first time since the current classification system was introduced in 1992.

In addition, fewer than 5% of the individual medal events in Paris will be for S2 athletes — all male.

This means a swimmer like Singapore’s Yip Pin Xiu[10] could miss out. Xiu won two golds in S2 swimming events at the 2016 Rio Games and a gold and silver at the 2008 Beijing Games, and is also competing in Tokyo. However, if there are no S2 women’s events in Paris, she might not be able to participate.

By contrast, athletes in the S9/S10 classes will have six times as many events as S1/S2 athletes.

The IPC recognises the unique barriers faced by people with severe impairments who wish to participate in sport. One of its strategic priorities[11] is to increase their participation in para sports across the spectrum. In this respect, the removal of events for these athletes from the Paralympic program is counterproductive.

The legitimacy of the Paralympics depends on inclusion

The IPC’s pursuit of a more inclusive world through sport is an honourable and laudable one. However, in order to be effective, it must start with a rigorous review of its own policies and procedures to make sure that, as an organisation, it is leading by example.

This means reviewing the event viability rule to make it more equitable and reinstating events for athletes with high support needs that were removed from the Paris program.

The IPC should also re-establish the Committee for Athletes with High Support Needs, which is charged with ensuring all sports rules and policies of the IPC are equitable and and inclusive.

This is crucial because, in the long run, the legitimacy of the Paralympic movement depends on not only retaining, but increasing the presence of athletes with severe impairments at the Games.

References

- ^ feature (www.paralympic.org)

- ^ agreement (www.who.int)

- ^ WeThe15 (www.wethe15.org)

- ^ A brief history of the Paralympic Games: from post-WWII rehabilitation to mega sport event (theconversation.com)

- ^ event viability rule (www.paralympic.org)

- ^ Paralympics haven't decreased barriers to physical activity for most people with disabilities (theconversation.com)

- ^ difference between equality and equity (inclusivesportdesign.com)

- ^ UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (www.un.org)

- ^ Why the 2000 Sydney Paralympics were such a success — and forever changed the games (theconversation.com)

- ^ Yip Pin Xiu (www.paralympic.org)

- ^ strategic priorities (www.paralympic.org)