What is the metaverse? A high-tech plan to Facebookify the world

- Written by Nick Kelly, Senior Lecturer in Interaction Design, Queensland University of Technology

Facebook chief executive Mark Zuckerberg recently announced[1] the tech giant will shift from being a social media company to becoming “a metaverse company”, functioning in an “embodied internet” that blends real and virtual worlds more than ever before.

So what is “the metaverse”? It sounds like the kind of thing billionaires talk about to earn headlines, like Tesla chief Elon Musk spruiking “pizza joints[2]” on Mars. Yet given almost three billion people use Facebook each month[3], Zuckerberg’s suggestion of a change of direction is worth some attention.

Read more: Mark Zuckerberg wants to turn Facebook into a 'metaverse company' – what does that mean?[4]

The term “metaverse” isn’t new, but it has recently seen a surge in popularity[5] and speculation about what this all might mean[6] in practice.

The idea of the metaverse is useful and it’s likely to be with us for some time. It’s a concept worth understanding even if, like me, you are critical of the future its proponents suggest.

The metaverse: a name whose time has come?

Humans have developed many technologies to trick our senses, from audio speakers and televisions to interactive video games and virtual reality, and in future we may develop tools to trick our other senses such as touch and smell. We have many words for these technologies, but as yet no popular word that refers to the totality of the mash-up of old-fashioned reality (the physical world) and our fabricated extensions to reality (the virtual world).

Words like “the internet” and “cyberspace[7]” have come to be associated with places we access through screens. They don’t quite capture the steady interweaving of the internet with virtual realities (such as 3D game worlds or virtual cities) and augmented reality[8] (such as navigation overlays[9] or Pokémon GO[10]).

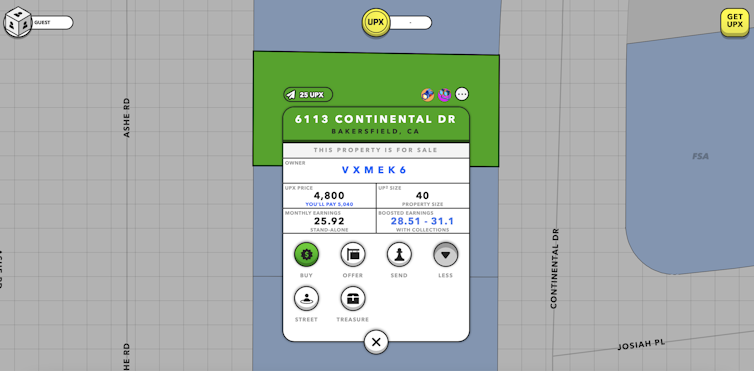

Just as important, the old names don’t capture the new social relationships, sensory experiences and economic behaviours that are emerging along with these extensions to the virtual. For example, Upland[11] mashes together a virtual reflection of our world with non-fungible tokens (NFTs) and property markets.

Upland is a kind of ‘metaverse’ property-trading game based on real-world addresses.

Upland

Upland is a kind of ‘metaverse’ property-trading game based on real-world addresses.

Upland

Facebook’s announcement speaks to its attempts to envision what social media within the metaverse might look like[12].

It also helps that “metaverse” is a poetic term. Academics have been writing about a similar idea under the name of “extended reality[13]” for years, but it’s a rather dull name.

“Metaverse”, coined by science fiction writer Neal Stephenson in his 1992 novel Snow Crash, has a lot more romantic appeal. Writers have a habit of recognising trends in need of naming: “cyberspace” comes from a 1982 book by William Gibson; “robot” is from a 1920 play by Karel Čapek.

Read more: Do we want an augmented reality or a transformed reality?[14]

Recent neologisms such as “the cloud[15]” or the “Internet of Things[16]” have stuck with us precisely because they are handy ways to refer to technologies that were becoming increasingly important. The metaverse sits in this same category.

Who benefits from the metaverse?

If you spend too long reading about big tech companies like Apple, Facebook, Google and Microsoft, you might end up feeling advances in technology (like the rise of the metaverse) are inevitable. It’s hard not to then start thinking about how these new technologies will shape our society, politics and culture, and how we might fit into that future.

This idea is called “technological determinism[17]”: the sense that advances in technology shape our social relations, power relations, and culture, with us as mere passengers. It leaves out the fact that in a democratic society we have a say in how all of this plays out.

For Facebook and other large corporations, determined to embrace the “next big thing” before their competitors, the metaverse is exciting because it presents an opportunity for new markets, new kinds of social network, new consumer electronics and new patents.

What’s not so clear is why you or I would be excited by all this.

A familiar story

In the mundane world, most of us are grappling with things like a pandemic, a climate emergency, and mass human-induced species extinction[18]. We are struggling to understand what a good life looks like with technology we’ve already adopted (mobile devices, social media and global connectivity are linked to many unwanted effects such as anxiety and stress[19]).

So why would we get excited about tech companies investing untold billions in new ways to distract us from the everyday world that gives us air to breathe, food to eat and water to drink?

Metaverse-style ideas might help us organise our societies more productively. Shared standards and protocols that bring disparate virtual worlds and augmented realities into a single, open metaverse could help people work together and cut down on duplication of effort.

In South Korea, for example, a “metaverse alliance[20]” is working to persuade companies and government to work together to develop an open national VR platform. A big part of this is finding ways to blend smartphones, 5G networks, augmented reality, virtual currencies and social networks to solve problems for society (and, more cynically, make profits).

Similar claims for sharing and collaboration were made in the early days of the internet. But over time the early promise[21] was swept aside by the dominance of large platforms and surveillance capitalism[22].

The internet has been wildly successful in connecting people all around the world to one another and functioning as a kind of modern Library of Alexandria[23] to house vast stores of knowledge. Yet it has also increased the privatisation of public spaces, invited advertising into every corner of our lives, tethered us to a handful of giant companies more powerful than many countries, and led to the virtual world consuming the physical world[24] via environmental damage.

Beyond the one-world world

The deeper problems with the metaverse are about the kind of worldview it would represent.

In one worldview, we we can think of ourselves as passengers inside a singular reality that is like a container for our lives. This view is probably familiar to most readers, and it also describes what you see on something like Facebook: a “platform” that exists independently of any of its users.

In another worldview, which sociologists suggest[25] is common in Indigenous cultures, each of us creates the reality that we live in through what we do. Practices such as work and rituals connect people, land, life and spirituality, and together create reality.

A key problem with the former view is that it leads to a “one-world world”: a reality that does not permit other realities. This is what we see already on existing platforms.

The current version of Facebook may increase your ability to connect to other people and communities. But at the same time it limits how you connect to them: features such as six preset “reactions” to posts and content chosen by invisible algorithms shape the entire experience. Similarly, a game like PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds (with more than 100 million active users) allows limitless possibilities for how a game might play out – but defines the rules by which the game can be played.

The idea of a metaverse, by shifting even more of our lives onto a universal platform, extends this problem to a deeper level. It offers us limitless possibility to overcome the constraints of the physical world; yet in doing so, only replaces them with constraints imposed by what the metaverse will allow.

References

- ^ announced (www.theverge.com)

- ^ pizza joints (www.gq.com.au)

- ^ each month (www.statista.com)

- ^ Mark Zuckerberg wants to turn Facebook into a 'metaverse company' – what does that mean? (theconversation.com)

- ^ surge in popularity (trends.google.com)

- ^ what this all might mean (www.matthewball.vc)

- ^ cyberspace (en.wikipedia.org)

- ^ augmented reality (theconversation.com)

- ^ navigation overlays (blog.google)

- ^ Pokémon GO (pokemongolive.com)

- ^ Upland (www.upland.me)

- ^ might look like (theconversation.com)

- ^ extended reality (www.wired.com)

- ^ Do we want an augmented reality or a transformed reality? (theconversation.com)

- ^ the cloud (theconversation.com)

- ^ Internet of Things (theconversation.com)

- ^ technological determinism (mitpress.mit.edu)

- ^ mass human-induced species extinction (advances.sciencemag.org)

- ^ anxiety and stress (www.bbc.com)

- ^ metaverse alliance (www.theregister.com)

- ^ early promise (www.pcmag.com)

- ^ surveillance capitalism (theconversation.com)

- ^ Library of Alexandria (www.britannica.com)

- ^ virtual world consuming the physical world (www.bbc.com)

- ^ sociologists suggest (www.tandfonline.com)

Read more https://theconversation.com/what-is-the-metaverse-a-high-tech-plan-to-facebookify-the-world-165326