a look inside the extraordinary preservation of a 310-million-year-old nervous system

- Written by John Paterson, Professor of Earth Sciences, University of New England

Charles Darwin famously discussed the “imperfections” of the geological record in his book On The Origin of Species. He correctly pointed out that unless conditions are just right, it’s unlikely for organisms to be preserved as fossils, even those with bones and shells.

He also said “no organism wholly soft can be preserved”.

Read more: Guide to the classics: Darwin's On the Origin of Species[1]

However, after more than a century of fossil hunting since his book was published, we now know the preservation of soft creatures is indeed possible — including some of the most fragile animals, such as jellyfish[2].

But what about the really delicate anatomy of animals, such as their internal organs? Can they be fossilised too?

Our study, published today in Geology[3], shows how even the intricate brains of ancient aquatic arthropods[4] (invertebrates with jointed legs) can be preserved in remarkable detail.

The discovery of a 310 million-year-old horseshoe crab[5] in the US, complete with its brain intact, adds to a recent string of fossil finds which have unearthed some of the oldest arthropods with a preserved central nervous system[6].

The horseshoe crab fossil we document in our study sheds new light on how these fragile organs — typically prone to very rapid decay — can be preserved with such fidelity.

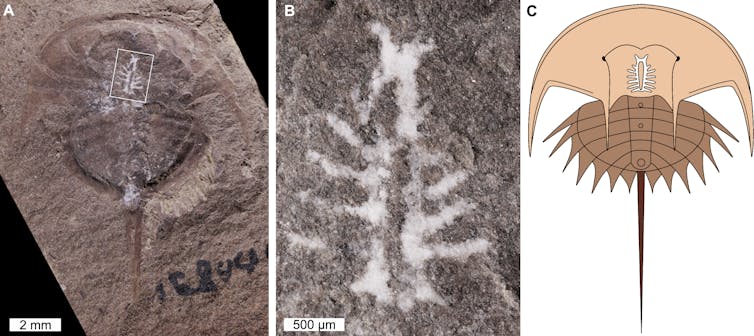

(A) Specimen of the fossil horseshoe crab Euproops danae from Mazon Creek, Illinois, USA, preserved with its brain intact. (B) Close-up of brain, as indicated by box in image (A). (C) Reconstruction of Euproops danae, including the position and anatomy of the brain.

Russell Bicknell

(A) Specimen of the fossil horseshoe crab Euproops danae from Mazon Creek, Illinois, USA, preserved with its brain intact. (B) Close-up of brain, as indicated by box in image (A). (C) Reconstruction of Euproops danae, including the position and anatomy of the brain.

Russell Bicknell

Brain freeze: how to fossilise an arthropod brain

Most of our knowledge of prehistoric arthropod brains has been sourced from two key types of fossil deposit: amber and those of Burgess Shale-type.

Amber[7] is fossilised resin that oozes through tree bark and is known to trap a variety of organisms. The entombed individuals[8] are commonly represented by arthropods such as insects — made famous in the original Jurassic Park[9] movie.

These fossils preserve an incredible amount of anatomical detail, as well as behaviours[10], mainly because very little decay takes place after the organism is rapidly trapped in the resin.

A centipede and a neighbouring ant suspended in roughly 23 million-year-old Mexican amber.

Greg Edgecombe

A centipede and a neighbouring ant suspended in roughly 23 million-year-old Mexican amber.

Greg Edgecombe

Using sophisticated imaging technology on these amber fossils, palaeontologists can study tiny arthropod brains in 3D at minuscule scales[11]. However, the oldest arthropods in amber[12] only extend back to the Triassic Period (around 230 million years ago).

Burgess Shale-type deposits[13] are much older, being Cambrian in age (typically 500 to 520 million years old). They contain an abundance of exceptionally preserved marine arthropods.

These fossils are very important as they represent what are unmistakably some of the oldest animals, and can therefore inform us on their origins and earliest evolutionary history. Their remains are primarily preserved as carbon films in mudstone.

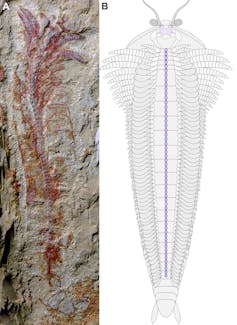

The Cambrian arthropod Chengjiangocaris kunmingensis from China. See the bead-like ventral nerve cord preserved in the fossil (A) and its central position in the reconstruction (B).

Javier Ortega-Hernández

The Cambrian arthropod Chengjiangocaris kunmingensis from China. See the bead-like ventral nerve cord preserved in the fossil (A) and its central position in the reconstruction (B).

Javier Ortega-Hernández

The fossilisation process starts with storm-induced mudflows that sweep up the delicate animals and bury them in the seafloor in low oxygen conditions. Over time, the mud turns to stone and is compressed, leaving the animals pancaked in the rocks.

Many Burgess Shale-type arthropod specimens preserve internal organs, especially the gut. But fewer show parts of the central nervous system, such as the optic nerves, ventral nerve cord or the brain.

Mind-boggling preservation

Our new fossil demonstrates arthropod brains can be preserved in an entirely different way. The specimen of the horseshoe crab, Euproops danae, comes from the world-famous Mazon Creek deposit[14] of Illinois, in the US. Fossils from this deposit are preserved within concretions made of an iron carbonate mineral called siderite.

Some of the Mazon Creek animals, such as the bizarre “Tully Monster”[15], are entirely soft-bodied. This suggests special conditions must have been in place to preserve them.

We have shown, for the first time, that the Mazon Creek animals were not only moulded by the rapid formation of siderite that entombed their entire bodies, but also that the siderite quickly encased their internal soft tissues before they could decompose.

Notably, the brain of Euproops is replicated by a white-coloured clay mineral called kaolinite. This mineral cast would have formed later within the void left by the brain, long after it had decayed. Without this conspicuous white mineral, we may have never spotted the brain.

A fossil no-brainer

One of the challenges of interpreting ancient arthropod anatomy is the lack of close modern relatives available for comparison. But luckily for us, Euproops can be compared to the four species of living horseshoe crabs.

Even to the untrained eye, a comparison of the fossil’s nervous system with that of a modern horseshoe crab (below) leaves little question that the same structures are found in both species, despite them being separated by 310 million years.

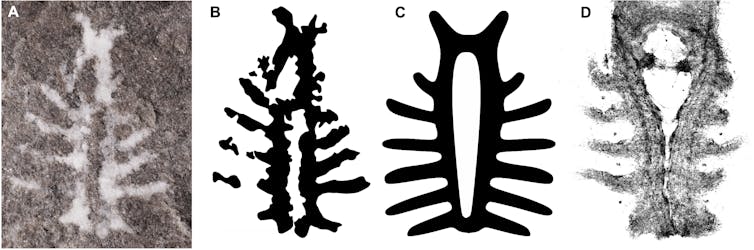

(A) The fossil and (B and C) interpretive drawings of the Euproops danae brain, and (D) the brain of a modern juvenile horseshoe crab, Limulus polyphemus.

(A-C) Russell Bicknell, (D) Steffen Harzsch

(A) The fossil and (B and C) interpretive drawings of the Euproops danae brain, and (D) the brain of a modern juvenile horseshoe crab, Limulus polyphemus.

(A-C) Russell Bicknell, (D) Steffen Harzsch

The fossil and living nervous systems match up in their arrangements of nerves to the eyes and appendages, and show the same central opening for the oesophagus to pass through.

Uncovering these exceptional specimens gives palaeontologists a rare glimpse into the deep past, enhancing our understanding of the biology and evolution of long-extinct animals. It seems Charles Darwin need not have been so pessimistic about the fossil record after all.

Read more: Our 500 million-year-old nervous system fossil shines a light on animal evolution[16]

References

- ^ Guide to the classics: Darwin's On the Origin of Species (theconversation.com)

- ^ jellyfish (www.nationalgeographic.com)

- ^ Geology (doi.org)

- ^ arthropods (australian.museum)

- ^ horseshoe crab (theconversation.com)

- ^ central nervous system (www.britannica.com)

- ^ Amber (www.britannica.com)

- ^ entombed individuals (cosmosmagazine.com)

- ^ Jurassic Park (www.youtube.com)

- ^ behaviours (eartharchives.org)

- ^ in 3D at minuscule scales (link.springer.com)

- ^ oldest arthropods in amber (www.amnh.org)

- ^ Burgess Shale-type deposits (burgess-shale.rom.on.ca)

- ^ Mazon Creek deposit (pubs.geoscienceworld.org)

- ^ “Tully Monster” (theconversation.com)

- ^ Our 500 million-year-old nervous system fossil shines a light on animal evolution (theconversation.com)