COVID-19 messages make emergency alerts just another text in the crowd on your home screen

- Written by Elizabeth Ellcessor, Associate Professor of Media Studies, University of Virginia

On a spring day in 2020, residents of El Paso, Texas, saw their phones light up with a text message: “Avoid parks/family gatherings this Easter. Stay home, stay safe. Do it for your loved ones.”

This message, sent via the federal Wireless Emergency Alert system[1], was one of many designed to deliver COVID-19-related guidance[2] directly to people’s cellphones.

COVID-19-related messages are a new use of this alert system. They indicate changing ideas about what constitutes an emergency and underscore the challenges of public messaging in a personalized media environment.

Traditionally, emergency alerts are sent to phones in a given area only in very serious circumstances: Amber Alerts[3] for abducted children, presidential alerts[4] for national emergencies, alerts about imminent threats to life or safety and alerts “conveying recommendations for saving lives and property[5].” Between 2012 and 2018, 96% of alerts were weather-related[6].

Emergency alerts are de facto declarations of emergencies, and people tend to respond accordingly.

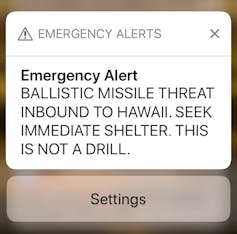

AP Photo/Caleb Jones[7]

Emergency alerts are de facto declarations of emergencies, and people tend to respond accordingly.

AP Photo/Caleb Jones[7]

As I explain in my forthcoming book, “In Case of Emergency: How Technologies Mediate Crisis and Normalize Inequality,” use of a technology designated for emergencies effectively declares an emergency, and when people believe they are in the midst of an emergency they often change their feelings and behavior. For instance, an alert that declared a “ballistic missile threat inbound” to Hawaii in January 2018 prompted some people to panic[8]. While this incident was quickly revealed to be a mistake[9] – a Hawaii Emergency Management Agency employee confused a drill for an actual emergency[10] – many people experienced an emergency: the fear, the confusion, the rush of activity.

Just another alert?

As Wireless Emergency Alert messages are being used for new kinds of emergencies, it’s more important than ever that public alert messaging is complete and straightforward. Yet there have been persistent challenges in COVID-19-related messaging, as seen in the El Paso alert. It addressed its public in terms of a religious holiday, indicating a lack of attention to diversity that could undermine some people’s trust in the system.

Furthermore, the message came without a clear indication of its sender. Nearly half[11] of early COVID-19-related alerts left out this information. This omission can lead to confusion about the trustworthiness of messages and a hesitance to take them seriously.

The possibility for confusion is amplified because emergency alerts pop up just like text messages, app alerts and similar push notifications on smartphones. Some alerts are sent alongside an audible tone, but there is little to distinguish emergency alerts from other messages on phones with sound turned off.

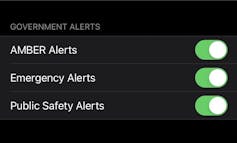

Emergency alerts can be turned off in iPhone settings, which provide little information.

Elizabeth Ellcessor, CC BY-ND[12]

Emergency alerts can be turned off in iPhone settings, which provide little information.

Elizabeth Ellcessor, CC BY-ND[12]

This makes it easy to perceive Wireless Emergency Alert messages as invasive, annoying or untrustworthy – spam or a scam – which could lead people to opt out of them. All emergency alerts, other than alerts the president sends to the nation[13], can be turned off in a phone’s settings menu.

But controlling phone alert settings is difficult, because the alert types are not explained and most people are unclear about how they might differ. Furthermore, the ease of opting out of alerts puts people at risk[14] because they might be left unaware of emergencies. Alerts are most useful when they are widely received, which means people opting out could compromise community safety.

‘This is a test. This is only a test.’

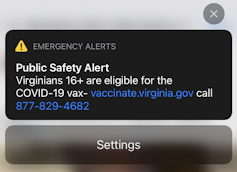

The April 2021 WEA message about COVID-19 vaccines sent in Virginia.

Elizabeth Ellcessor

The April 2021 WEA message about COVID-19 vaccines sent in Virginia.

Elizabeth Ellcessor

The growing use of Wireless Emergency Alert messages calls for better public education and awareness about mobile emergency alerts. Many people still react to such messages with uncertainty, irritation and intense emotion. For example, some people reacted to Virginia’s recent public safety message about COVID-19 vaccine availability with anger about being frightened[15] by an alert that they assumed indicated an emergency.

People of a certain age likely remember the regular testing of the Emergency Broadcast System: television screens displayed a test pattern as a message was read aloud followed by a long loud tone. Similar tests occur today on radio and television broadcasts as part of the Emergency Alert System[16].

A test of the Emergency Broadcast System that was broadcast on Los Angeles TV station KTTV Channel 11 in 1983.Such tests familiarize people with the system. Wireless Emergency Alert messages could also be tested with messages that provide information about options, message types and so on. Unfortunately, a 2018 test of the presidential alert[17] did none of these things. It caused most cellphones in the country to emit a tone and receive a text message declaring a test of the Wireless Emergency Alert system but provided no further instruction. As a technical test, it succeeded, but as public education, it left much to be desired.

Alerts about COVID-19 broadened the scope of the kinds of emergencies that can be addressed via emergency alerts, but without sustained efforts to regularly build public awareness and familiarity with the system, these changes can sow uncertainty and breed distrust.

This broadened scope shows the importance of public education about the nature of alerts, the options available in the technology, and how to interpret messages’ origins, severity and relevance. Doing so is vital for keeping people and communities safe.

[The Conversation’s most important coronavirus headlines, weekly in a science newsletter[18]]

References

- ^ Wireless Emergency Alert system (www.fcc.gov)

- ^ deliver COVID-19-related guidance (www.dhs.gov)

- ^ Amber Alerts (amberalert.ojp.gov)

- ^ presidential alerts (www.azcentral.com)

- ^ conveying recommendations for saving lives and property (www.fcc.gov)

- ^ 96% of alerts were weather-related (www.oig.dhs.gov)

- ^ AP Photo/Caleb Jones (newsroom.ap.org)

- ^ prompted some people to panic (www.youtube.com)

- ^ mistake (www.washingtonpost.com)

- ^ confused a drill for an actual emergency (www.cnn.com)

- ^ Nearly half (ascelibrary.org)

- ^ CC BY-ND (creativecommons.org)

- ^ alerts the president sends to the nation (www.theatlantic.com)

- ^ puts people at risk (products.abc-clio.com)

- ^ anger about being frightened (www.washingtonpost.com)

- ^ Emergency Alert System (www.fema.gov)

- ^ 2018 test of the presidential alert (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ The Conversation’s most important coronavirus headlines, weekly in a science newsletter (theconversation.com)