How do the 'yes' and 'no' cases stack up? Constitutional law experts take a look

- Written by Gabrielle Appleby, Professor, UNSW Law School, UNSW Sydney

In the coming weeks, Australians will be asked to vote “yes” or “no”[1] to the constitutional amendment[2] to recognise Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people through establishing a body known as the Voice.

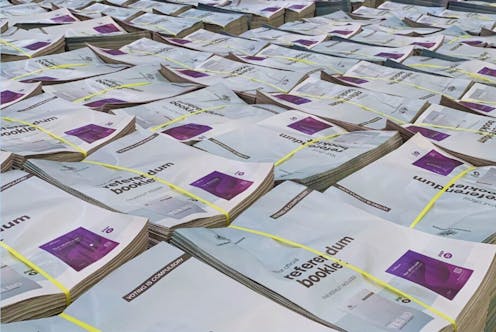

Anticipating the referendum, the Australian Electoral Commission has started to post to every voter the official “yes” and “no” cases[3]. These cases were approved by the politicians who voted in favour of, or against, the amendment in parliament. They have not been subject to an independent fact check or analysis before publication. The Australian Electoral Commission has not reviewed or endorsed them.

As members of the Gilbert + Tobin Centre of Public Law and the Indigenous Law Centre, we have spent the past few weeks carefully reviewing the substantive claims made in the official “yes” and “no” cases. We wanted to identify where the claims are based on history, facts and research, where the claims need further explanation, and where the claim is misleading or simply unsupported.

Read more: 10 questions about the Voice to Parliament - answered by the experts[4]

Our analysis reveals the claims made to support the “yes” case are accurate. They are based in the historical development of the Voice proposal by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, and the ongoing support within their communities for the reform. They are supported by significant Australian and international research that practical progress will be made in areas such as health, housing and education when governments listen to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. This in turn results in better value for money in the long term.

The “yes” claims are informed by the vast weight of opinion from legal experts who have considered the wording of the draft amendment that the Australian people will be voting on. They reflect the government’s publicly agreed commitments for the future design of the Voice.

In contrast, the claims made to support the “no” case are largely misleading. Many of the claims simply ignore the existence of contrary facts and history.

The “no” case ignores, for instance, the views of the vast majority of legal experts that the amendment is not risky, or that significant details have been provided to the Australian people about the constitutional amendment and the future design of the Voice.

It also misrepresents the current position of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people under the Constitution. It implies the Voice will bring discrimination and unequal treatment, whereas human rights experts agree the Voice proposal is consistent with the right to equality and provides recognition for the First Nations’ unique history, culture and connection to land.

The claims misrepresent the Voice as a bureaucracy and ignore the existence of significant research that demonstrates that structural changes such as the Voice will result in better practical outcomes. The “no” case misrepresents the scope and powers of the Voice, inaccurately explaining the constitutional limits on these while ignoring the practical and political limits.

Our analysis reveals that Australian voters need to be wary when reading the official pamphlet and making up their minds on the Voice. They will need to separate out the factual, supported claims from those that are misleading, unsupported or just plain wrong. Our report is designed to help voters with that process.

In our view, the “no” case has failed voters. It does not cater to the millions of Australians who want to hear fair-minded arguments in relation to the constitutional amendment before they make up their minds.

References

- ^ “yes” or “no” (www.aec.gov.au)

- ^ constitutional amendment (voice.gov.au)

- ^ official “yes” and “no” cases (www.aec.gov.au)

- ^ 10 questions about the Voice to Parliament - answered by the experts (theconversation.com)