You've heard the annoyingly catchy song – but did you know these incredible facts about baby sharks?

- Written by Jaelen Nicole Myers, PhD Candidate, James Cook University

“Baby shark doo-doo doo-doo doo-doo, baby shark doo-doo doo-doo doo-doo …” If you’re the parent of a young child, you’re probably painfully familiar with this infectious song, which now has more than 13 billion views[1] on YouTube.

The Baby Shark song, released in 2016, has got hordes of us singing along, but how much do you really know about baby sharks? Do you know how a baby shark is born, or how it survives to become an apex predator?

I study coastal marine ecology. I believe baby sharks are truly fascinating, and I hope greater public knowledge about these creatures will help protect them in the wild.

So sink your teeth into this Q&A on the weird and wonderful world of baby sharks.

How are baby sharks conceived and born?

To the human eye, shark courtship practices may seem barbaric. Males typically attract the attention of a female by biting her. If successful, this is generally followed by even toothier bites to hold on during copulation[2]. Females can carry the scars of these encounters long after the mating season is over.

The act of copulation itself is comparable to that of humans. The male inserts its sexual organ, known as a “clasper”, into the female and releases sperm to fertilise the eggs[3].

However, in extremely rare cases, sharks can reproduce asexually – in other words, embryos develop without being fertilised. This occurred at a Queensland aquarium in 2016, when a zebra shark gave birth[4] to a litter of pups despite not having had the chance to mate in several years.

Sharks give birth in a variety of ways. Some species produce live pups[5], which swim away to fend for themselves as soon as they’re born. Others hatch from eggs outside the mother’s body. Remnants of these egg cases have been found washed up on beaches across the world.

How big is a litter of shark pups?

Litter size across sharks varies considerably. For example, the grey nurse shark starts with several embryos but only two are born. This is because the embryos actually eat each other while in utero! This leaves only one survivor in each of the mother’s two uteruses.

Intrauterine cannibalism[6] may seem disturbing but is nature’s way of ensuring that the strongest pups get the best chance of survival.

In contrast, other species such as the whale shark[7] use a completely different strategy to ensure some of their offspring survive: having hundreds of pups in a single litter.

Where do baby sharks live?

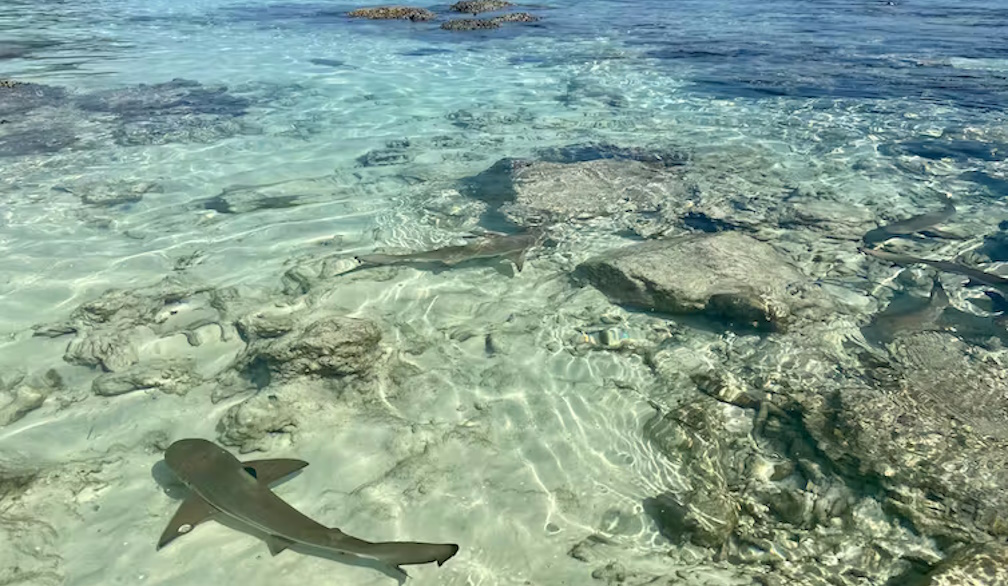

The open ocean is a dangerous place. That’s why pregnant female sharks often give birth in shallow coastal waters known as “nurseries”. There, baby sharks are better protected from harsh environmental conditions and roaming predators, including other sharks.

Sites for shark nurseries include river mouths, estuaries, mangrove forests and coral reef flats.

For example, the white shark has established nursery grounds along the east coast[8] of Australia, where babies may remain for several years before moving to deeper waters.

Although most types of sharks are confined to saltwater, the bull shark can live[9] in freshwater habitats. Bull shark pups born near river mouths and estuaries often migrate upstream[10] (sometimes vast distances inland) to escape being preyed upon.

Read more: How do fishes scratch their itches? It turns out sharks are involved[11]

When are baby sharks born?

Sharks, like most animals in the wild, generally give birth during periods that provide favourable conditions for their offspring.

In Australia, for example, scalloped hammerheads[12] and bull sharks[13] tend to breed in the wet summer months when nursery grounds are warmer and there are rich feeding opportunities.

How long do baby sharks take to grow up?

Sharks grow remarkably slowly[14] compared to other fish and remain juveniles for a long time. Although some species mature in a few years[15], most take considerably longer.

Take the Greenland shark – the world’s longest living shark. It can live to at least 250 years[16] and according to recent research[17], it’s thought to take more than a century to reach sexual maturity[18].

Read more: Surfers share their waves with sharks, but fear not[19]

What threats do baby sharks face?

While small, sharks must eat or be eaten – all the while enduring the elements and finding enough food to survive and grow.

Yet there is another challenge: humans. In fact, we are the greatest threat[20] to sharks.

Shark nurseries are heavily concentrated in coastal zones, and often overlap with human activities such as fishing, boating and coastal development. And because sharks grow so slowly[21], they are particularly to vulnerable to overfishing[22] because when populations decline, they can take a long time to bounce back.

Much more to learn

Scientists are still working to understand the life cycles of the 500-plus species of sharks[23] in our oceans. Each time I hear the song Baby Shark, it reminds me there’s a lot more work to do.

It’s crucial to keep monitoring and studying these baby wonders of the deep, to ensure shark populations survive and we maintain the delicate balance of our underwater ecosystems.

Read more: When we swim in the ocean, we enter another animal's home. Here's how to keep us all safe[24]

References

- ^ more than 13 billion views (www.youtube.com)

- ^ during copulation (www.bing.com)

- ^ fertilise the eggs (ocean.si.edu)

- ^ gave birth (www.sciencealert.com)

- ^ live pups (www.sharktrust.org)

- ^ Intrauterine cannibalism (www.australiangeographic.com.au)

- ^ whale shark (www.fisheries.noaa.gov)

- ^ east coast (www.australiangeographic.com.au)

- ^ can live (australian.museum)

- ^ migrate upstream (www.abc.net.au)

- ^ How do fishes scratch their itches? It turns out sharks are involved (theconversation.com)

- ^ scalloped hammerheads (www.dpi.nsw.gov.au)

- ^ bull sharks (www.abc.net.au)

- ^ remarkably slowly (saveourseas.com)

- ^ few years (journals.plos.org)

- ^ at least 250 years (oceanservice.noaa.gov)

- ^ recent research (www.nationalgeographic.com)

- ^ sexual maturity (oceanservice.noaa.gov)

- ^ Surfers share their waves with sharks, but fear not (theconversation.com)

- ^ greatest threat (australian.museum)

- ^ so slowly (saveourseas.com)

- ^ overfishing (www.sharktrust.org)

- ^ 500-plus species of sharks (ocean.si.edu)

- ^ When we swim in the ocean, we enter another animal's home. Here's how to keep us all safe (theconversation.com)