Australia is set for a hot, dry El Niño. Here’s what that means for our flammable continent

- Written by Kevin Tolhurst AM, Hon. Assoc. Prof., Fire Ecology and Management, The University of Melbourne

An El Niño event has arrived[1], according to the World Meteorological Organization, raising fears of record high global temperatures, extreme weather and, in Australia, a severe fire season.

The El Niño is a reminder that bushfires are part of Australian life – especially as human-caused global warming worsens. But there are a few important considerations to note.

First, not all[2] El Niño years result in bad bushfires. The presence of an El Niño is only one factor that determines the prevalence of bushfires. Other factors, such as the presence of drought, also come into play.

And second, whether or not this fire season is a bad one, Australia must find a more sustainable and effective way to manage bushfires. The El Niño threat only makes the task more urgent.

Understanding fire in Australia

An El Niño is declared[3] when the sea surface temperature in large parts of the tropical Pacific Ocean warms significantly.

The statement[4] by the World Meteorological Organization, released on Tuesday, said El Niño conditions have developed in the tropical Pacific for the first time in seven years “setting the stage for a likely surge in global temperatures and disruptive weather and climate patterns”.

The organisation says there’s a 90% probability of the El Niño event continuing during the second half of 2023. It said El Niño can trigger extreme heat and also cause severe droughts over Australia and other parts of the world.

But before we start planning ahead for the next bushfire season, it’s important to understand what drives bushfire risks – and the influence of climate change, fire management and events such as El Niño.

The evidence for human-induced climate change is irrefutable[5]. While the global climate has changed significantly in the past[6], the current changes are occurring at an unprecedented rate.

In geologic time scales, before the influence of humans, a significant shift[7] in climate has been associated[8] with an increase in fire activity in Australia. There is every reason to expect fire activity will increase with human-induced climate change as well.

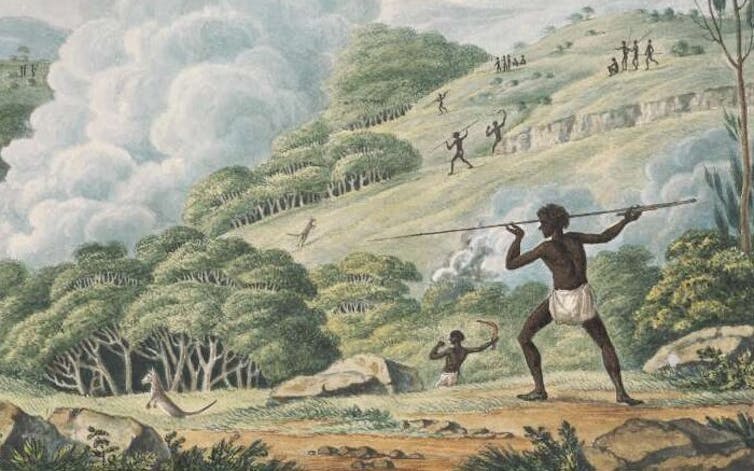

Humans have also changed the Australian fire landscape – both First Nations people and, for the past 200 years, European colonisers.

Changes brought about by Indigenous Australians were widespread, but sustainable[9]. Their methods included, for example, lighting “cool” fires in small, targeted patches early in the dry season. This reduced the chance that very large and intense fires would develop.

Read more: Our land is burning, and Western science does not have all the answers[10]

Changes brought about by European colonisers have also been widespread – such as land clearing using fire, and fire suppression to protect human life and property. But this approach has been far from sustainable[11], either financially, ecologically or socially.

Australia has just experienced a period of high rainfall across the continent due to a La Niña event combined with[12] two other climate drivers: a negative Indian Ocean Dipole and a positive Southern Annular Mode. It means the soil is moist and plants are flourishing.

Now, we’re set to enter into a drying period driven by an El Niño. The abundant plant growth leading into a dry period is likely to result in widespread bushfires across Australia.

Initially, this is likely to occur[13] in semi-arid inland areas where grasses have flourished in the wet period, but will dry out quickly. If the drying cycle persists for two or three years, then fires might become more prevalent in forests and woodlands in temperate Australia.

But an El Niño year doesn’t necessarily mean a bad bushfire season is certain.

In Australia, El Niño events are associated with hotter and drier conditions, leading to more days[14] of high fire danger. But large and severe forest fires also need a prolonged drought to dry out fuels, especially in sheltered gullies and slopes. Soils and woody vegetation are currently moist following the La Niña period.

So El Niño and its opposite phase, La Niña, are on their own are a relatively poor predictor[15] of the number and size of bushfires.

Read more: The burn legacy: why the science on hazard reduction is contested[16]

Fight smarter, and be prepared

Climate change will continue to test our fire management systems. And the return of an El Niño has fire crews on alert[17].

When it comes to fire management, Australia must be much smarter than it has been for the past 200 years. This means changing the focus to holistic fire management. Throwing huge amounts of money and resources at controlling bushfires – such as purchasing more[18] and larger firefighting aircraft[19] – is is not sustainable or sensible.

Fire is as fundamental to our environment as wind and rain. And the amount of energy released from a large bushfire will never be matched by any level of resources humans can muster.

The evidence bears this out. Take, for example, analysis[20] of fire dynamics in two areas north and south of the US-Mexico border. Between 1920 and 1972, authorities on the US side had spent hundreds of millions of dollars on firefighting aircraft and other resources trying to suppress wildfires. This resulted in fewer wildfires than in the Mexico region. But the fires that occurred were larger and more severe.

Similar patterns have occurred in Australia. For example, a study[21] of burn patterns in the Western Desert region showed that after the exodus of Traditional Owners, the number of fires reduced substantially, but the fires became far bigger.

Read more: Watching our politicians fumble through the bushfire crisis, I'm overwhelmed by déjà vu[22]

Change must happen

Damaging bushfires will return to Australia in the near future. The expected return of another El Niño should heighten efforts to create a more considered and sustainable fire management regime – particularly in southern Australia.

Experts, including me, have devised[23] plans[24] to guide the shift. They include:

- effectively managing the land with fire, including promoting Indigenous Australians’ use of fire

- engaging communities in bushfire mitigation and management

- better coordination across land, fire and emergency management agencies

- ensuring fire management is based on “best practice” approaches.

Australia, with its wealth of scientific knowledge and long history of Indigenous land management, should be well placed to manage fire sustainably – even with the pressures of climate change. Changing our approach will not be quick or simple, but it must be done.

References

- ^ arrived (public.wmo.int)

- ^ not all (www.bom.gov.au)

- ^ declared (www.climate.gov)

- ^ statement (public.wmo.int)

- ^ irrefutable (www.ipcc.ch)

- ^ in the past (theconversation.com)

- ^ shift (publications.csiro.au)

- ^ associated (www.publish.csiro.au)

- ^ sustainable (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- ^ Our land is burning, and Western science does not have all the answers (theconversation.com)

- ^ far from sustainable (www.researchgate.net)

- ^ combined with (climateextremes.org.au)

- ^ likely to occur (knowledge.aidr.org.au)

- ^ leading to more days (www.researchgate.net)

- ^ poor predictor (research.monash.edu)

- ^ The burn legacy: why the science on hazard reduction is contested (theconversation.com)

- ^ on alert (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ purchasing more (www.canberratimes.com.au)

- ^ firefighting aircraft (www.news.com.au)

- ^ analysis (www.publish.csiro.au)

- ^ study (www.researchgate.net)

- ^ Watching our politicians fumble through the bushfire crisis, I'm overwhelmed by déjà vu (theconversation.com)

- ^ devised (www.forestry.org.au)

- ^ plans (knowledge.aidr.org.au)