To deliver enough affordable housing and end homelessness, what must a national strategy do?

- Written by Chris Martin, Senior Research Fellow, City Futures Research Centre, UNSW Sydney

The Albanese government came to office promising action on housing. Its A$10 billion Housing Australia Future Fund[1] is now stuck in the Senate, with the Greens demanding[2] more ambitious funding and reforms. The government is also working on its promised National Housing and Homelessness Plan[3].

In research published today[4] by the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI), we make the case for a housing and homelessness strategy to be an ambitious national project. Its central mission should be to ensure everyone has adequate housing.

We outline the goals, scope and institutions the strategy needs to succeed. The housing numbers it should deliver to meet demand – including 950,000 social and affordable rental dwellings by 2041 – dwarf current government targets[5].

Our report draws on new thinking about the need for “mission-oriented” governments to tackle complex problems, as well as policy-making approaches here and overseas.

Why a strategy?

Strategies help to clarify the purpose of action for everyone. They bring together information and expertise that inform and stimulate public discussion. They help define priorities.

This is important for housing and homelessness problems because they are complex. They cross over different policy areas and levels of government. They have diverse causes and broad effects.

By the same token, solving these problems can produce diverse benefits.

The goal of “adequate housing for everyone” – the first target of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 11[6] – states the challenge clearly.

To meet that challenge, it is useful to think of governments and stakeholders being engaged in a mission[7] that requires government to lead the deliberate shaping of markets and direction of economic activity. Fixing market failures and filling unprofitable gaps in the market isn’t enough.

It’s also useful to think about the special status of governments in financial systems. The Australian government is the issuer and guarantor of money[8]. It can use this status to finance missions for the public good.

For example, for two years of the COVID-19 emergency, the Reserve Bank of Australia bought bonds[9] issued by federal, state and territory governments totalling $5 billion per week. That’s equivalent to one Housing Australia Future Fund every fortnight.

Fragmented approach causes problems

Because Australia is a federation, the federal government must work with state and territory governments to implement policies. Most intergovernmental activity has involved housing and homelessness conceived of as welfare issues.

Responsibility for housing and homelessness policy is divided. The National Housing and Homelessness Agreement[10] guides policy, but is clearly deficient[11]. Development of other policy levers, such as Commonwealth Rent Assistance[12], has languished.

The National Housing Finance and Investment Corporation (NHFIC[13]) finances and supports efforts to increase the supply of housing, particularly affordable housing. The NHFIC is becoming increasingly important as its functions expand. It’s getting a new name, Housing Australia, to match its remit.

The financial regulators, the Reserve Bank and the Australian Prudential Regulatory Authority (APRA), are arguably conducting housing policy of their own.

Housing policy responsibilities at the state and territory level are similarly fragmented.

Lessons from other national strategies

We examined Canada’s National Housing Strategy[14]. Its rights-based approach, statutory basis and accountability agencies are important innovations.

However, the Canadian strategy is narrowly focused on affordable rental housing. Key issues of tax and finance are beyond its scope. Looking to European housing policy leaders, such as Austria[15] and Finland[16], we can see the value of broader national strategies and dedicated housing agencies.

We can also learn from other national approaches to policy in Australia, such as Closing the Gap[17] and Australia’s Disability Strategy[18].

The first lesson is that making a strategy is itself a strategic exercise. Reformers need to develop the capacity to take on and influence established institutions, vested interests and entrenched ways of thinking.

A dedicated lead agency may be needed to coordinate strategy development and implementation. Accountability is crucial. By this we mean more than accounting for the spending of public money. It is also about demonstrating commitment to the reform process and the people it serves.

What should the strategy’s goals be?

The strategy should have a clear mission: everyone in Australia has adequate housing.

The strategy should be comprehensive, with a set of secondary missions:

homelessness is prevented and ended

social housing meets needs and drives wider housing system improvement

the system offers more genuine choice – including between ownership and renting

housing quality is improved

housing supply is improved

housing affordability is improved

the housing system’s contribution to wider economic performance is improved.

And what policy areas are covered?

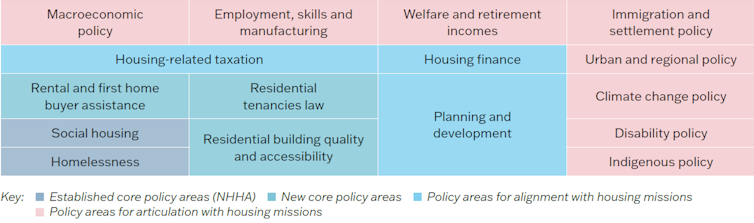

The diagram below shows the strategy’s scope and stages. It begins with the familiar core policy areas covered by the National Housing and Homelessness Agreement (bottom left). As the scope of the strategy expands (up and to the right), the intensity of housing policy leadership varies accordingly.

Social housing and homelessness are core policy areas for the strategy. To meet current and future need[20], it should aim to add 950,000 social and affordable rental housing dwellings by 2041. That’s about 50,000 new dwellings a year – a lot more than the 8,000 a year over five years[21] that the Albanese government has promised so far.

The most cost-effective way to finance this growth is a mix of NHFIC bonds and capital grants from government. State and territory governments should make plans to regularly reassess need and delivery.

Housing assistance, residential tenancies law and building quality should be new core policy areas. The National Cabinet’s recent decision[22] to develop a tenancy law reform agenda to strengthen tenants’ rights is a welcome step.

Housing-related taxation, housing finance and planning and development regimes should be aligned with Australia’s housing and homelessness missions.

Existing national strategies for First Nations and people with disability need strengthening on housing and homelessness as a matter of priority.

The strategy should be laid down in law. The legislation should enshrine the right to adequate housing, nominate Housing Australia as the lead agency, and establish regulatory and accountability agencies.

The author acknowledges his report co-authors, Associate Professor Julie Lawson, Honorary Professor Vivienne Milligan, Chris Hartley, Professor Hal Pawson and Professor Jago Dodson.

References

- ^ Housing Australia Future Fund (ministers.treasury.gov.au)

- ^ demanding (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ National Housing and Homelessness Plan (www.dss.gov.au)

- ^ research published today (www.ahuri.edu.au)

- ^ government targets (ministers.treasury.gov.au)

- ^ Sustainable Development Goal 11 (www.un.org)

- ^ mission (www.ucl.ac.uk)

- ^ issuer and guarantor of money (www.abc.net.au)

- ^ bought bonds (www.rba.gov.au)

- ^ National Housing and Homelessness Agreement (federalfinancialrelations.gov.au)

- ^ deficient (www.pc.gov.au)

- ^ Commonwealth Rent Assistance (www.dss.gov.au)

- ^ NHFIC (www.nhfic.gov.au)

- ^ Canada’s National Housing Strategy (www.placetocallhome.ca)

- ^ Austria (housingpolicytoolkit.oecd.org)

- ^ Finland (housingpolicytoolkit.oecd.org)

- ^ Closing the Gap (www.closingthegap.gov.au)

- ^ Australia’s Disability Strategy (www.disabilitygateway.gov.au)

- ^ AHURI (www.ahuri.edu.au)

- ^ current and future need (cityfutures.ada.unsw.edu.au)

- ^ 8,000 a year over five years (ministers.treasury.gov.au)

- ^ recent decision (www.pm.gov.au)