are they becoming more common? A seismology expert explains

- Written by Dee Ninis, Earthquake Geologist, Monash University

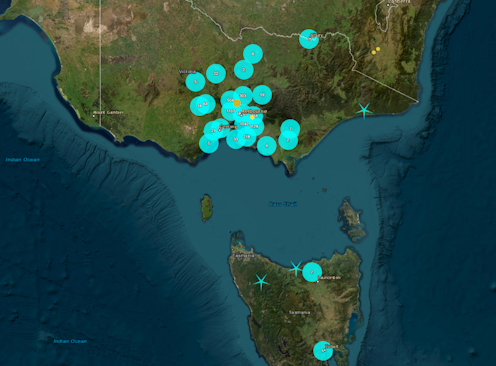

Last night at 11:41pm local time, the greater Melbourne region was shaken by a magnitude 4.0 earthquake – as calculated by the Seismology Research Centre[1] – centred near Sunbury, approximately 30km north of the CBD.

Geoscience Australia have so far received more than 25,000 reports[2] from people who felt this earthquake, some as far as Hobart, which is 620km away from the epicentre.

In the Melbourne region, the earthquake reportedly produced shaking which lasted roughly 10–20 seconds, according to witness reports on social media. It was followed two minutes later by a magnitude 2.8 aftershock, which was reported by some people in the epicentral region between Sunbury and Cragieburn.

Are earthquakes becoming more common in Melbourne?

In September 2021, a magnitude 5.8 earthquake rattled Melbourne[3], its epicentre being at Woods Point[4] to the east of the city. This earthquake was felt as far away as Brisbane and Adelaide.

Last night’s earthquake follows a magnitude 2.5 earthquake[5] near Ferntree Gully, to the east of Melbourne, two weeks ago on May 16. Another one with a magnitude of 2.0 was felt by about 1,300 people in roughly the same region on May 22[6], according to Geoscience Australia.

Although this means some Melbournians have experienced two or even three earthquakes in the last two weeks, earthquakes are not becoming more common in Melbourne. It is not unexpected for there to be 10–12 felt earthquakes a year somewhere in the greater Melbourne region – these need not occur at regular intervals.

Earthquakes in Australia occur as a result of stresses at our surrounding tectonic plate boundaries – where different plates collide, grind past one another, or are being forced apart. These stresses make their way towards the middle of the plate, too.

In southeast Australia, the forces at the Pacific-Australian plate boundary[7] to the east of us – the same plate boundary which passes through Aotearoa New Zealand – produce a buildup of strain. This is eventually released in the form of earthquake ruptures at weak zones or “faults” in the crust.

As a result of all this, earthquakes occur in the greater Melbourne region about once a month. Many of these – typically more than three quarters – are too small to be felt.

Read more: Nobody can predict earthquakes, but we can forecast them. Here's how[8]

What determines if you feel an earthquake?

Generally speaking, a larger magnitude earthquake is more likely to be felt than those of smaller magnitudes. But other factors play a part, too.

Earthquake depth affects how strong the associated ground shaking is – the shallower the earthquake, the stronger the shaking. Last night’s magnitude 4.0 near Sunbury was a relatively shallow earthquake at just 3km depth. Because shallow earthquakes produce stronger ground-shaking, they’re also more likely to cause damage. Minor damage, such as cracked plaster[9] and fallen pictures[10], were reported as a result of last night’s earthquake.

Read more: Why are shallow earthquakes more destructive? The disaster in Java is a devastating example[11]

The closer you are to the earthquake epicentre, the more likely you are to feel it. You’re also more likely to experience an earthquake if you’re stationary, rather than jogging or riding a bike or driving. Some people reportedly slept through last night’s earthquake.

The earthquakes reported as felt by those near the epicentre are mostly ones above a magnitude 2.0–2.5, although smaller events can be felt especially at shallow depths, and in populated areas. If an earthquake happens in a remote region, there are often no people to report having felt it.

Booms and aftershocks

Very small, shallow earthquakes sometimes do not produce any shaking closest to the epicentre, but instead produce a sound akin to an explosion – a short, sharp, loud “boom”. This occurs when the seismic waves reach the surface and transform into sound waves.

This is different to the rumbling sound which is more commonly heard, and is often described as a train approaching. It’s the result of the shaking of the built environment as the seismic wave passes through.

In addition to the magnitude 2.8 aftershock from last night’s earthquake, there have been additional aftershocks less than magnitude 1.0. These are still being examined by seismologists. There may still be aftershocks large enough to be felt in the coming days, weeks, and months, though the likelihood of these diminishes with time.

Occasionally, a larger earthquake may occur, in which case the magnitude 4.0 will be considered a foreshock.

Read more: The earthquake that rattled Melbourne was among Australia's biggest in half a century, but rock records reveal far mightier ones[12]

References

- ^ calculated by the Seismology Research Centre (www.src.com.au)

- ^ so far received more than 25,000 reports (earthquakes.ga.gov.au)

- ^ rattled Melbourne (theconversation.com)

- ^ at Woods Point (earthresources.vic.gov.au)

- ^ magnitude 2.5 earthquake (earthquakes.ga.gov.au)

- ^ in roughly the same region on May 22 (earthquakes.ga.gov.au)

- ^ at the Pacific-Australian plate boundary (www.eastcoastlab.org.nz)

- ^ Nobody can predict earthquakes, but we can forecast them. Here's how (theconversation.com)

- ^ cracked plaster (twitter.com)

- ^ fallen pictures (twitter.com)

- ^ Why are shallow earthquakes more destructive? The disaster in Java is a devastating example (theconversation.com)

- ^ The earthquake that rattled Melbourne was among Australia's biggest in half a century, but rock records reveal far mightier ones (theconversation.com)