COVID remains a global emergency, the World Health Organization says, but we're at a transition point. What does this mean?

- Written by Hassan Vally, Associate Professor, Epidemiology, Deakin University

As we enter the fourth year of living with COVID, we are all asking the predictable question: when will the pandemic be over?

To answer this question, it’s worth reminding ourselves that a pandemic[1] involves the worldwide spread of a disease that requires an emergency response at a global level.

This week, World Health Organization (WHO) Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus declared[2] COVID continues to be a public health emergency of international concern.

As Ghebreyesus notes, we still face significant challenges, with high rates of transmission in many countries, the risk of a game-changing new variant ever-present, and an unknown impact of long COVID.

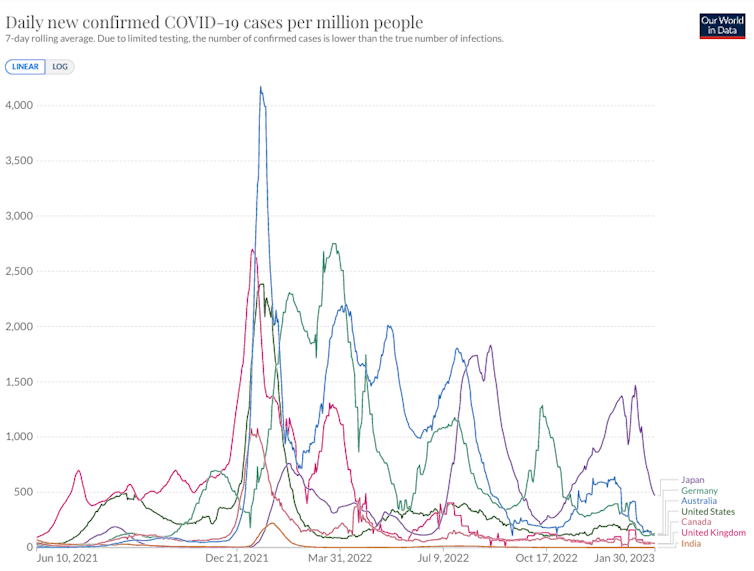

Yet COVID pandemic “fatigue” means it’s harder to reach people[5] with public health messaging, while misinformation continues to circulate. In addition, many countries have deprioritised COVID testing and surveillance, so we don’t have accurate data about the extent of transmission.

But while we’re still in the emergency phase of our COVID response, three years after the original declaration, the WHO also acknowledged we’re at a transition point. This means we’re moving towards the “disease control” phase of our response to COVID and learning to live with the virus.

What are we transitioning to?

Moving out of the emergency response phase for COVID doesn’t mean ignoring COVID or returning to exactly what our lives looked like before March 2020. Rather, we need to learn to coexist with COVID.

Living with COVID means applying appropriate prevention and control measures for COVID as we go about our lives. This is what we do for other infectious diseases, including other respiratory diseases.

Read more: We're entering a new phase of COVID, where we each have to assess and mitigate our own risk. But how?[6]

The most effective thing we can do to reduce the risk of COVID is to be up-to-date with our vaccinations and boosters. COVID vaccines don’t completely stop transmission, but they greatly reduce[7] your likelihood of becoming seriously ill.

We can also reduce the likelihood of spreading COVID by masking up in high-risk settings, socialising in well-ventilated spaces, and staying away from others when unwell.

Living with COVID also involves government continuing with public health actions to monitor disease transmission and to prevent, control and respond to infections.

What has prompted the transition?

We’ve entered the transition phase because the risk associated with COVID has shifted. Thanks to safe and effective vaccines, along with high levels of prior infection, we have increased immunity at the population level and COVID infection is less likely[8] to lead to severe disease.

This, combined with the emergence of less virulent variants[9] (for now) and the addition to our armoury of a number of effective treatment[10] options, has reduced the overall threat COVID poses to health. The position we are in now is very different to where we were at the beginning of the pandemic.

Read more: How has COVID affected Australians' health? New report shows where we've failed and done well[11]

One of the main characteristics of this transition phase of the pandemic is a shift towards a risk-based approach to COVID. The focus of public health interventions will be to target the most vulnerable to COVID in the community. This means ensuring older age groups, those with underlying health conditions and others at increased risk of severe outcomes from COVID are adequately protected.

What might get in the way?

A smooth path through this transition phase and into the next phase is reliant on continuing to maintain a high level of population immunity overall. One of the biggest challenges is how to promote the uptake of vaccines as the perceived threat of COVID fades.

The difficulty in ensuring a high uptake of boosters is a worldwide problem. Waning immunity[13], which could be topped up with additional vaccine doses, remains a significant concern and we need to find better ways to address this issue.

The main challenge for health authorities right now is to, on the one hand, acknowledge the reduction in the risk COVID poses while, on the other hand, ensuring people don’t become complacent and completely ignore COVID.

Health authorities are also propping up very fatigued and stretched health systems.

So when will it end?

The WHO’s recognition we are entering a transition phase of the pandemic means we’re one step closer to the end of the pandemic. But while pandemics begin with a bang, they don’t end that way.

Pandemics fade as individuals and populations gradually return to living their lives in a more “normal” way as their risk changes. This can be incredibly messy, with countries transitioning out of the emergency response phase of the pandemic at different times.

So the pandemic isn’t over but an end is in sight.

Read more: COVID will soon be endemic. This doesn't mean it's harmless or we give up, just that it's part of life[14]

References

- ^ pandemic (theconversation.com)

- ^ declared (www.who.int)

- ^ Our World in Data/Johns Hopkins University CSSE COVID-19 Data (ourworldindata.org)

- ^ CC BY (creativecommons.org)

- ^ harder to reach people (www.who.int)

- ^ We're entering a new phase of COVID, where we each have to assess and mitigate our own risk. But how? (theconversation.com)

- ^ greatly reduce (theconversation.com)

- ^ less likely (www.covid19data.com.au)

- ^ less virulent variants (theconversation.com)

- ^ treatment (theconversation.com)

- ^ How has COVID affected Australians' health? New report shows where we've failed and done well (theconversation.com)

- ^ Shutterstock (www.shutterstock.com)

- ^ Waning immunity (www.washingtonpost.com)

- ^ COVID will soon be endemic. This doesn't mean it's harmless or we give up, just that it's part of life (theconversation.com)