how adult literacy programs can keep First Nations people out of the criminal justice system

- Written by Jack Beetson, Executive Director, The Literacy for Life Foundation; Adjunct Professor, University of New England

Despite years of discussion and countless reviews, the incarceration rate of First Nations adults continues to increase[1] in Australia. The federal government has said[2] it will address this via “justice reinvestment”. That means funding programs that keep people out of the justice system.

Justice reinvestment reduces ever-growing criminal justice system costs, which frees up more funding to invest in communities. That keeps more people out of the system. And so the positive cycle continues.

One part of the justice reinvestment picture may be boosting literacy rates. In fact, a growing body of research shows the crucial role community-controlled adult literacy campaigns can play in reducing crime and improving justice outcomes.

Read more: To lift literacy levels among Indigenous children, their parents' literacy skills must be improved first[3]

A 65% drop in serious offences after literacy training

An estimated 40-70%[4] of First Nations adults have low literacy.

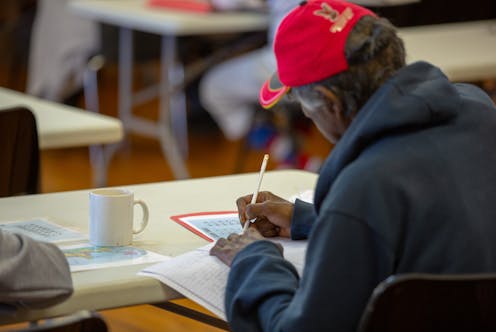

Our research has focused on boosting literacy rates among First Nations adults via free programs rolled out by the Literacy for Life Foundation[5].

These programs involve more than 100 hours of adult literacy classes and activities, led by local Aboriginal staff, over a period of six months.

Our study[6], published in the International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy[7], found that after participation in the Literacy for Life Foundation adult literacy campaign, serious offences by students dropped by almost 65%.

The research was conducted as a before-and-after study looking at six communities in New South Wales. It included 162 participants who were all students in Literacy for Life Foundation’s Aboriginal adult literacy campaign. We also drew on NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research data. Study participants consented to researchers examining their criminal offence records relating to the 12-month period prior to participation in the literacy campaign, and 12-month period after participation.

The study also drew on more than 100 interviews with students, staff, community members, service providers and criminal justice practitioners.

We found:

total offences recorded (including those categorised as serious, plus other categories) declined by 32% (from 71 to 48)

among women in the study, total offences halved (from 40 to 20).

the largest reductions related to traffic offences (down 50%, from 14 to seven), public order offences (down 56%, from nine to four) and theft offences (down from five to zero).

One community leader described the impact for one participant by saying:

By the time he’d finished, he came out the other side not only having the ability to read and write, but he also came out of the other side with a licence. So that was a life-changing experience.

Low literacy can mean more contact with the justice system

Our study is among a growing body of research[8] that highlights the correlation between low adult literacy and contacts with the police.

So what’s one got to do with the other?

Lower levels of English literacy are considered one of many factors contributing to continued inequalities[9] in health and social outcomes for Indigenous peoples. One major area of inequality is in crime and justice.

Systemic racism and discriminatory policies across multiple sectors and over generations have contributed to Indigenous Australians facing more contacts[10] with police, higher rates of incarceration and more contact with courts.

For many Indigenous people, entry into the judicial system is through minor, non-violent offences such as traffic infringements[11], in part due to insufficient literacy skills needed to pass a written driver’s licence[12] test.

Low levels of English literacy also affect[13] a person’s ability to understand their legal rights, seek legal counsel and read official documentation such as court attendance notifications. Not showing up to court proceedings can also result in additional charges being laid.

Convictions for these minor offences leave people with a criminal record, which make it hard to get a job. That can exacerbate issues with health and social wellbeing and perpetuate cycles of disadvantage.

Building basic literacy skills can help[14] keep people out of jail, and for those in prison, participation in literacy and numeracy programs while in custody can help reduce recidivism (reoffending).

The Literacy for Life Foundation has recently started work with Indigenous people serving sentences in prison and it is hoped the trends highlighted in our study can be replicated.

What’s already clear is that community-led adult literacy campaigns can help reduce serious offences among participants by well over 50%, meaning the benefits extend beyond just helping people to read and write.

Research on this can help justice reinvestment programs, turning policy aspirations into practical action.

Read more: 'Once students knew their identity, they excelled': how to talk about excellence in Indigenous education[15]

References

- ^ increase (www.sbs.com.au)

- ^ said (www.abc.net.au)

- ^ To lift literacy levels among Indigenous children, their parents' literacy skills must be improved first (theconversation.com)

- ^ 40-70% (www.news.com.au)

- ^ Literacy for Life Foundation (www.lflf.org.au)

- ^ study (www.crimejusticejournal.com)

- ^ International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy (www.crimejusticejournal.com)

- ^ research (www.aic.gov.au)

- ^ continued inequalities (www.cambridge.org)

- ^ more contacts (www.pc.gov.au)

- ^ traffic infringements (journals.sagepub.com)

- ^ pass a written driver’s licence (equityhealthj.biomedcentral.com)

- ^ also affect (apo.org.au)

- ^ can help (www.ncver.edu.au)

- ^ 'Once students knew their identity, they excelled': how to talk about excellence in Indigenous education (theconversation.com)