A Vietnam veteran anthropologist and an Arnhem Land community have worked together for over 40 years. Don Watson tells their story.

- Written by Timothy Michael Rowse, Emeritus Professor, Western Sydney University

With The Passion of Private White[1], Don Watson has written a witty and compassionate book about friendship, Indigenous self-determination and people under stress.

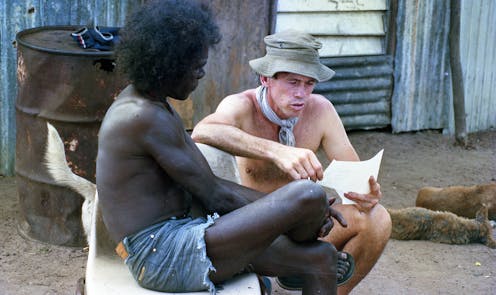

“Private White” is Neville White, an anthropologist and Vietnam veteran who has spent two months a year since 1974 in Arnhem Land, as a guest of Yolngu families residing at the Donydji community.

Watson explains:

For the last forty years, all the Indigenous people of north-east Arnhem Land (Miwatj) have been known as Yolngu – which means “person” or “people” or “human being”. They number about 3000 and all are members of one or other of several dozen intermarrying culturally connected clans.

Review: The Passion of Private White – Don Watson (Scribner)

Yolngu self-determination

Donydji[2] is an experiment in self-determination – that is, in Yolngu choosing the degree and forms of their involvement in Australian institutions. Before his first visit to Donydji, White was told that

alone among the Yolngu clans, the people living here had never left their lands. Here, and only here, would he find a clan whose traditional knowledge was intact.

Two policy changes in the mid-1970s afforded a greater margin of choice for Yolngu, including the residents of Donydji. In 1976, the Fraser government’s Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act[3] gave Yolngu title to the entire Arnhem Land Reserve, including the right to veto mining.

Until 1975, unemployment benefits were not available to remote Aboriginal people (as, in the absence of a local labour market, they were not seen as seeking employment). Without needing a change in legislation, the Department of Social Security decided to make unemployment benefits available to these previously excluded people.

This created a new and substantial income stream for remote communities such as Donydji, and many of them began to avail themselves of it in the form of the Community Development Employment Program[4]. This income relieved them of the pressure to say “yes” to economic development.

Donydji became a permanent camp in 1971. Sitting down at Donydji was driven by the desire of certain Ritharrngu and Wagilak families to safeguard Country from exploration – such as test-drilling that had violated a site in the late 1960s. Donydji is strategically located on a road and an airstrip graded to service mining exploration.

So, to preserve their traditional lands, the families at Donydji have modified their way of life. Erecting shelters and demanding basic services such as schooling and access to manufactured goods, they have become sedentary.

You can learn all this by reading White’s history of Donydji[5] – downloadable (free) from Australian National University Press. He describes some of the consequences of Yolngu becoming sedentary.

At Donydji, Yolngu live on a combination of what they can forage and what they can purchase, and they seek whatever material support governments and citizens can offer them. They are gripping their country and they are gripped by it. As well, they are gradually losing some knowledge that had been essential to nomadic foraging.

Homeland Story (Ronin Films) is a documentary about the Donydji community, and Dr Neville White’s work. At time of publication, it can be viewed on SBS on Demand.Read more: Paul Daley's Jesustown: a novel of lurid, postcolonial truth-telling[6]

An anti-Vietnam War veteran

What Watson brings to this story is his compassionate, sardonic appreciation of White (an old university friend), his Yolngu hosts and the Vietnam veterans[7] who have assembled over many dry seasons as Donydji’s volunteer construction gang. White knows these men because he served with them. So this is not only a book about Yolngu self-determination.

Labelling White “an old-school Australian”, Watson explores his own affinity with this cohort of ageing white men whose troubled bond is their service in a war he experienced only through the antiwar movement. At the same time (and from a greater distance), Watson narrates his experience of getting to know Yolngu, through his many visits to Donydji. Watson’s well-honed and affectionate sense of the absurd flavours every anecdote. But the deeper subject of this book is what binds and divides men.

Neville White grew up in working-class Geelong. His father, Leo White, was a champion boxer and trainer of Aboriginal fighters. Becoming Neville’s friend brought young (“sport-addicted”) Don closer to a milieu he had reverently imagined.

Don and Neville could agree, when they met at university in 1968, that Australia should not be committing troops to Vietnam. But by then, Neville had already served. Accepting conscription (in the third ballot, on September 10 1965) while disputing Australia’s commitment, he had spent the second half of 1967 as an infantryman.

Bonds forged with other soldiers outweighed – in their moral force – Neville’s rejection of Australia’s policy. “He would hardly be the first,” Watson comments, “to fight a war in which he did not believe.” White’s demobilisation was not of his choosing either. The bitter politics of conscription had made it prudent to limit conscripts to two years of service.

His sudden extraction from the battlefield left White feeling like he had deserted his comrades. Coming home was almost as baffling as the fighting itself. “For Neville’s experience of the battlefield the anti-Vietnam War movement had no affirmative words, or sympathy, or respect.”

That sense of failure still agitated White in a December 2021 conversation recounted by Watson. However, by then White had found a way to remake battlefield mateship – annually mobilising several of his old platoon as a volunteer construction gang at Donytji. A day’s hard work – punctuated by “chiacking” – concluded with mutual solicitations, as the men reminded one another to take the medications required to keep post-traumatic stress disorder[8] (PTSD) at bay.

Neville White is thus the hinge connecting the two “tribes” (the Yolngu residents and the visiting Vietnam vets) that annually find common purpose at Donydji.

Read more: The forgotten Australian veterans who opposed National Service and the Vietnam War[9]

At ease with anthropology

But in 1974, when White began to camp and observe at Donydji, he didn’t set out to connect the two parts of his life – soldier and anthropologist/guest – in this way. His early mode at Donydji was respectfully detached, in the name of science. The data he collected included fingerprints (a measure of genetic distribution). Some now revile anthropology as colonial zoo-keeping.