After floods will come droughts (again). Better indicators will help us respond

- Written by Neal Hughes, Adjunct Associate Professor, Centre for Regional and Rural Futures, Deakin University

Since late 2020, the La Niña[1] climate pattern has led to two years of above-average rainfall across much of Australia, and severe floods in parts of the country.

In areas spared the flooding, this rainfall has been good news for farmers, with improved conditions and high prices driving production and profits to record highs.

But the next drought is rarely too far away. For a reminder, we only need to look overseas, where the same La Niña weather system is combining with climate change to produce severe droughts in the United States[2], eastern Africa[3] and South America[4].

Unfortunately, drought can be difficult to define and measure. Determining whether a region or farm is “in drought” is a longstanding and complex problem, which remains important to our future drought response.

Drought is about more than rainfall

For a long time, Australia’s standard measure of drought has been rainfall. But while rainfall indicators are easy to produce and interpret, they can be a poor measure of a farm’s prospects.

For one thing, the impact of drought depends on the timing of rain.

Even when the year’s total rainfall is okay, if most of it arrives at the wrong time of year (such as outside the crop season) it can have the same impact as a drought.

Temperatures are also increasingly important, with record heat waves having an important effect in recent years.

The story gets more complicated still when droughts affect the prices of inputs to farms. For example, during the 2018-19 drought many dairy farms were impacted by high hay and water prices, even where they received rain.

Measuring farm impacts

In response, researchers including myself at the Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences (ABARES) have developed a new drought indicator based on predictions of farm financial outcomes[5], with some advantages over measures based on only rain.

In some cases it presents a very different picture.

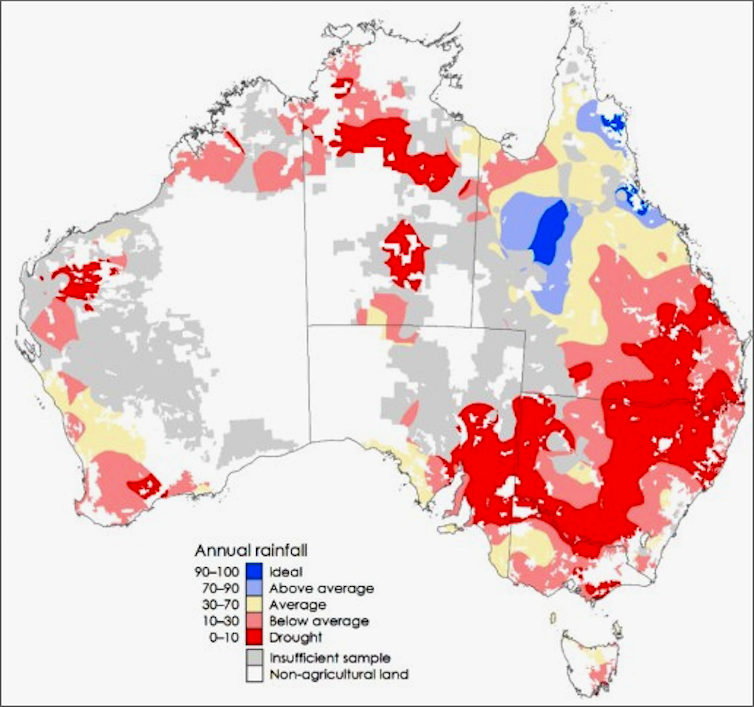

In the example below, for 2018-19, the indicator shows more severe impacts in parts of New South Wales than the rainfall model (because low rainfall was compounded by high temperatures and input prices), and less severe impacts in Western Australia (partly because of high grain prices resulting from shortages on the east coast).

Rain-based indicator:

Model-based indicator:

Drought declarations are mattering less

Since the early 2000s, drought policy has evolved away from in-drought support of farm businesses to an approach that emphasises preparedness and resilience, making explicit drought “declarations” less common.

While this change has been welcome, it also led to a reduced focus on drought impact measurement (with the exception of some state-level systems[8]).

But as recent droughts have shown, information on the extent and severity of drought impacts is still very important.

Read more: Helping farmers in drought distress doesn't help them be the best[9]

For one, it can help governments anticipate and prepare for increased demand for farm programs such as the Farm Household Allowance or the Rural Financial Counselling Service.

It can also help to better target resources for community, animal welfare or mental health drought impacts.

Better indicators can also support the development of new insurance products such as index-based weather insurance[10].

Such products are more likely to take off where indexes (and therefore payouts) can closely match real-world outcomes.

Early warnings are mattering more

While there is some evidence[11] climate change has exacerbated recent droughts in Australia, there remains much uncertainty over the longer term effects.

Regardless, the potential for more extreme weather events is generally increasing the importance of early warning systems.

ABARES is working with the CSIRO and the Bureau of Meteorology to develop a Drought Early Warning System[12] that will use this new indicator and a range of other tools to translate weather data into estimates of likely farm impacts.

Predicting these impacts remains very difficult, with challenges both in weather forecasting (particularly on monthly or longer time scales), and in translating these forecasts into agricultural outcomes.

But any improvements we can make will help us better respond to what the future has in store.

Read more: Farms are adapting well to climate change, but there's work ahead[13]

References

- ^ La Niña (www.bom.gov.au)

- ^ United States (theconversation.com)

- ^ eastern Africa (theconversation.com)

- ^ South America (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ predictions of farm financial outcomes (www.sciencedirect.com)

- ^ ABARES (www.sciencedirect.com)

- ^ ABARES (www.sciencedirect.com)

- ^ state-level systems (edis.dpi.nsw.gov.au)

- ^ Helping farmers in drought distress doesn't help them be the best (theconversation.com)

- ^ index-based weather insurance (theconversation.com)

- ^ some evidence (theconversation.com)

- ^ Drought Early Warning System (www.agriculture.gov.au)

- ^ Farms are adapting well to climate change, but there's work ahead (theconversation.com)