Labelling 'fake art' isn't enough. Australia needs to recognise and protect First Nations cultural and intellectual property

- Written by Nicola St John, Lecturer, Communication Design, RMIT University

The latest draft report[1] from the Productivity Commission on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander visual arts and crafts confirms what First Nations artists have known for decades: fake art harms culture.

Released last week, the report details how two in three Indigenous-style products, souvenirs or digital imagery sold in Australia are fake, with no connection to – or benefit for – Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

This is a long-standing problem. As Aboriginal Elder Gawirrin Gumana (Yolngu) explained[2] in 1996:

When that [white] man does that it is like cutting off our skin.

The Productivity Commission has proposed all inauthentic Indigenous art should be labelled as such. But we think a much bolder conversation needs to happen around protecting the cultural and intellectual property of Indigenous artists.

Australia has no national licensing or production guidelines to protect Indigenous cultural and intellectual property within commercial design and digital spaces. Our work hopes to see this change.

Read more: Indigenous cultural appropriation: what not to do[3]

‘This is storytelling’

Our research[4] focuses on supporting and representing First Nations artists within design and commercial spaces, understanding how to ensure cultural safety and appropriate payment and combat exploitation.

Many First Nations artists we spoke to told us stories of exploitative business models. They were blindly led into licensing agreements and client relations that were not culturally safe. Clients thought commissioning a design equated to “owning” the copyright to First Nations art, culture and knowledge.

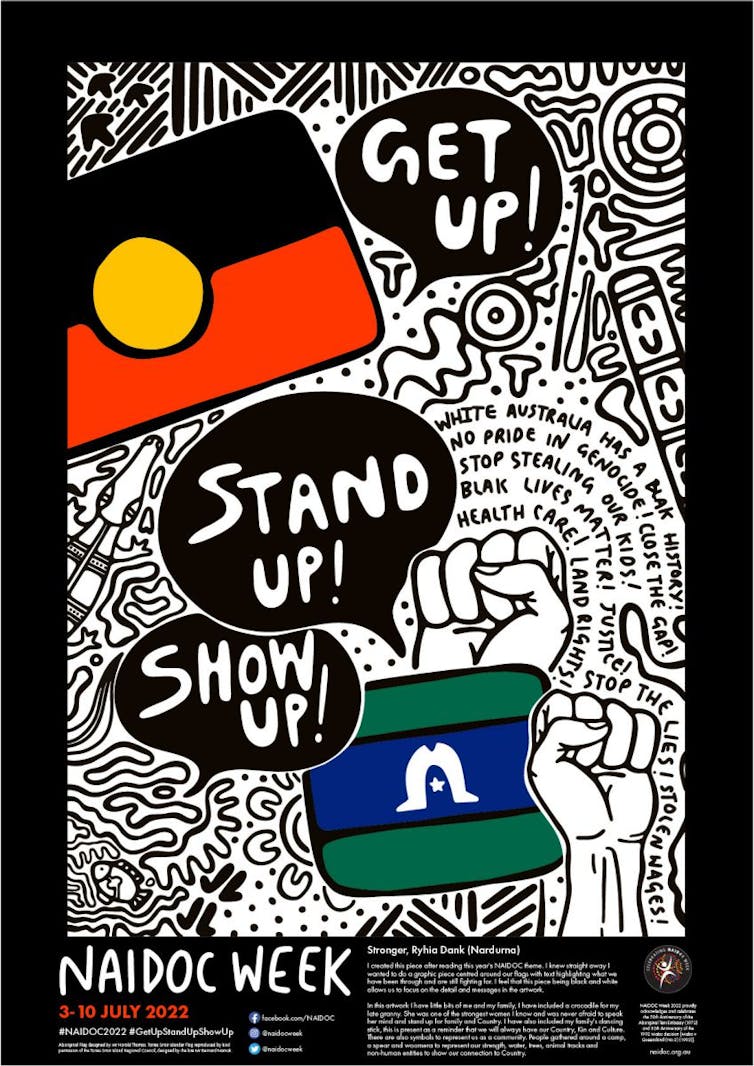

Gudanji/Wakaja artist and winner of the 2022 NAIDOC poster competition Ryhia Dank[5] told us:

We need clear recognition, structures and licensing guidelines to protect all of what First Nations ‘art’ represents. I know a lot of us, as we are starting out don’t know how to licence our work […]

One of my first designs was for a fabric company and I didn’t licence the design correctly, so that company is still using my design and I only once charged them $350 and that was it. Having legal support from the start is critical.

Arrernte and Anmatyerre graphic novelist Declan Miller[7] explained how many clients and businesses are misguided in thinking commissioning a design equates to owning the copyright to First Nations knowledges.

“Our art is not just art,” he said.

Clients need to be aware this is storytelling. This is culture. We will always own that. But we are happy for clients to work with us, and use our art and pay us for it, but we have to keep that integrity. This is our story, this is where we are from, this is who we are and you can’t buy that or take that from us.

Protecting property

Transparent labelling of inauthentic art is a great start, but there is more work needed.

Intellectual property laws and processes should adequately protect First Nations art.

“Indigenous cultural and intellectual property” refers to the rights First Nations people have – and want to have – to protect their traditional arts, heritage and culture.

This can include communally owned cultural practices, traditional knowledge and resources and knowledge systems developed by First Nations people as part of their First Nations identity.

First Nations products should be supplied by a First Nations business that protects Indigenous cultural and intellectual property, with direct benefits to First Nations communities.

The outcomes of our research have resulted in the recent launch of Solid Lines[8] – Australia’s only First Nations illustration agency to be led by First Nations people. An integral part of this agency is the Indigenous cultural and intellectual property policy designed specifically for the design and commercial art industry.

The agency hopes this policy, created with Marrawah Law[9], will help create and support culturally safe and supportive pathways for First Nations creatives.

For First Nations artists represented by Solid Lines, our policy also means obtaining culturally appropriate approval to use family or community stories, and knowledges and symbols that are communally owned.

Read more: How Indigenous fashion designers are taking control and challenging the notion of the heroic, lone genius[10]

Recognition and protection

The report from the Productivity commission focuses on fake art coming in from overseas, but fake art also happens in our own backyard.

In our research, we have spoken to Elders, traditional custodians, and community leaders who are concerned that Western and Central Desert designs, symbols and iconography are now used by other First Nations across Australia.

This work often undermines customary laws and limits economic benefits flowing back to communities.

Community designs, symbols and iconography are part of a cultural connection to a specific land or country of First Nations people. Embracing Indigenous cultural and intellectual property policies will mean designs, symbols and iconography can only be used by the communities they belong to.

The Productivity Commission calculated the value of authentic Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander arts, crafts, and designs sold in Australia in 2019-2020 at A$250 million. This will only continue to grow as Australia’s design and commercial industries continue to draw upon the oldest continuing culture in the world.

Visible recognition and protection of First Nations cultural and intellectual property will allow for new creative voices to respectfully and safely emerge within Australian art and design industries.

Through embracing guidelines around Indigenous cultural and intellectual property, First Nations artists will be supported in cultural safety, appropriate payment and combat exploitation. This is the next step beyond labelling inauthentic art.

Read more: Friday essay: how the Men's Painting Room at Papunya transformed Australian art[11]

References

- ^ draft report (www.pc.gov.au)

- ^ explained (catalogue.nla.gov.au)

- ^ Indigenous cultural appropriation: what not to do (theconversation.com)

- ^ Our research (apo.org.au)

- ^ Ryhia Dank (nardurna.com)

- ^ CC BY-NC-ND (creativecommons.org)

- ^ Declan Miller (www.stickmobstudio.com.au)

- ^ Solid Lines (solidlines.agency)

- ^ Marrawah Law (marrawahlaw.com.au)

- ^ How Indigenous fashion designers are taking control and challenging the notion of the heroic, lone genius (theconversation.com)

- ^ Friday essay: how the Men's Painting Room at Papunya transformed Australian art (theconversation.com)