Australian booksellers are facing a supply chain 'crisis'. Here's how books get into your hands – and how you can keep reading

- Written by Elizabeth Jackson, Senior Lecturer in Supply Chain Management & Logistics, Curtin University

Australians have been warned[1] to do their Christmas shopping early, as international supply chain issues are impacting global shipping. One industry under particular pressure is that of books, with printers, publishers and booksellers in Australia, the United States and Britain feeling the impact at their most important time of year.

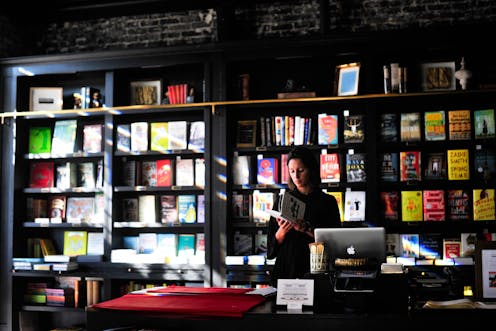

Chris Redfern, who owns three Avenue Bookstores in Melbourne, recently told the ABC[2] booksellers are facing “a crisis”.

While book supply chains are being affected globally, in the United States[3], paper and cardboard scarcity, along with labour shortages, are pressuring the situation at the printing press.

In the UK, a shortage of lorry drivers[4] is limiting stock movement. This part of the supply chain is also being impacted in Australia. Our three major book distributors all use one company to distribute their books, and the company is reportedly “overwhelmed with demand[5].”

Use of a single service provider for freight makes sense for purposes of cost control, but it’s a high-risk strategy, particularly during times when flow cycles are so disrupted.

A problem for smaller players

Supply chains operations are highly-coordinated. They aim to get the right product, in the right way, in the right quantity and quality, to the right person and place at the right time at the right cost.

Most booksellers embrace the low-cost, fast-paced principles of lean supply chains[6]: inventories are minimised with few resources wasted on books sitting idly in warehouses.

Most of the time, being able to respond to the market with agility exposes publishers, input suppliers, printers, transporters, warehouses and retailers to minimal risk.

But this careful balance of coordinating everything begins to show stress when even one part is impacted – let alone the multiple stressors of COVID.

In the US, publishers are encouraging[7] early ordering and bulk buying and holding large quantities of inventories to satisfy consumer demands. Large Australian book retailers like QBD and Booktopia have organised themselves in similar ways[8].

But smaller players, such as independent bookshops, are less able to buy in bulk or maintain large inventories. They are more likely to order only what they reasonably believe they can sell, quickly ordering more books in relation to demand.

There are some 1,900 bookstores[9] in Australia that contribute about A$1.4 billion to the national economy. Most of the market – 84% – is made up of small players.

Read more: Love of bookshops in a time of Amazon and populism[10]

Even pre-COVID, the industry has been under increasing pressure. Between 2016 and 2021, the industry contracted by 6.1%[11], and it was expected to continue to fall. Printing of books was on the decline, and many bookstores shut or reduced their capacity.

Paper, printing, binding, logistics and warehousing have all been exposed to COVID-19 disruptions. But at the same time, when COVID hit, demand for books suddenly increased[12] as people looked for amusement to get them through lockdown. The sudden increase in demand forced an industry in decline to play catch-up.

Books are still easy to find

However supply chain issues shouldn’t be impacting our reading at all. There is a cheap, accessible and innovative form of books not reliant on many of the steps in the traditional book supply chain: ebooks.

Readers are now capable of using technology to circumvent the printing and delivery process by buying and instantly downloading books at very low cost. But printed books are still in demand.

In 2020, 15.9% of Australians purchased an ebook[13] but 41.2% purchased a printed book. This is in sharp contrast[14] to music sales: physical music sales in Australia in 2020 accounted for just 11% of sales revenue.

Read more: Has the print book trumped digital? Beware of glib conclusions[15]

It has been suggested people prefer the physical texture of books[16] and our brains are hardwired to inherently process analogue information[17]. In spite of the promising adoption of new reading technologies we remain wedded to the printed word – but even this doesn’t mean we should remain wedded to supply chains.

For those dedicated to print, there are many more options: choosing a book you haven’t heard of from your local bookshop, buying from second-hand bookstores, borrowing from libraries, swapping books with friends and participating in local little libraries.

Supply chains may be impacting the shelves of your favourite independent book seller, but there is no reason they should impact your reading joy.

References

- ^ been warned (www.choice.com.au)

- ^ told the ABC (www.abc.net.au)

- ^ the United States (www.publishersweekly.com)

- ^ shortage of lorry drivers (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ overwhelmed with demand (www.abc.net.au)

- ^ lean supply chains (www.british-assessment.co.uk)

- ^ encouraging (www.publishersweekly.com)

- ^ similar ways (www.abc.net.au)

- ^ 1,900 bookstores (my.ibisworld.com)

- ^ Love of bookshops in a time of Amazon and populism (theconversation.com)

- ^ 6.1% (my.ibisworld.com)

- ^ demand for books suddenly increased (www.weforum.org)

- ^ purchased an ebook (www.gizmodo.com.au)

- ^ sharp contrast (www.dropbox.com)

- ^ Has the print book trumped digital? Beware of glib conclusions (theconversation.com)

- ^ people prefer the physical texture of books (www.forbes.com)

- ^ analogue information (scitechconnect.elsevier.com)