an introduction to Confucius, his ideas and their lasting relevance

- Written by Yu Tao, Senior Lecturer in Chinese Studies, The University of Western Australia

The man widely known in the English language as Confucius was born around 551 BCE in today’s southern Shandong Province. Confucius is the phonic translation of the Chinese word Kong fuzi 孔夫子, in which Kong 孔 was his surname and fuzi is an honorific for learned men.

Widely credited for creating the system of thought we now call Confucianism, this learned man insisted he was “not a maker but a transmitter”, merely “believing in and loving the ancients”. In this, Confucius could be seen as acting modestly and humbly, virtues he thought of highly.

Or, as Kang Youwei[1] — a leading reformer in modern China has argued — Confucius tactically framed his revolutionary ideas as lost ancient virtues so his arguments would be met with fewer criticisms and less hostility.

Confucius looked nothing like the great sage in his own time as he is widely known in ours. To his contemporaries, he was perhaps foremost an unemployed political adviser who wandered around different fiefdoms for some years, attempting to sell his political ideas to different rulers — but never able to strike a deal.

It seems Confucius would have preferred to live half a millennium earlier, when China — according to him — was united under benevolent, competent and virtuous rulers at the dawn of the Zhou dynasty. By his own time, China had become a divided land with hundreds of small fiefdoms, often ruled by greedy, cruel or mediocre lords frequently at war.

But this frustrated scholar’s ideas have profoundly shaped politics and ethics in and beyond China ever since his death in 479 BCE. The greatest and the most influential Chinese thinker, his concept of filial piety, remains highly valued among young people in China[2], despite rapid changes in the country’s demography.

Despite some doubts[3] as to whether many Chinese people take his ideas seriously, the ideas of Confucius remain directly and closely relevant to contemporary China.

This situation perhaps is comparable to Christianity in Australia. Although institutional participation is in constant decline, Christian values and narratives remain influential on Australian politics[4] and vital social matters[5].

The danger today is in Confucianism being considered the single reason behind China’s success or failure. The British author Martin Jacques, for example, recently asserted[6] Confucianism was the “biggest single reason” for East Asia’s success in the handling of the COVID-19 pandemic, without giving any explanation or justification.

If Confucius were alive, he would probably not hesitate to call out this solitary root of triumph or disaster as being lazy, incorrect and unwise.

Political structure and mutual responsibilities

Confucius wanted to restore good political order by persuading rulers to reestablish moral standards, exemplify appropriate social relations, perform time-honoured rituals and provide social welfare.

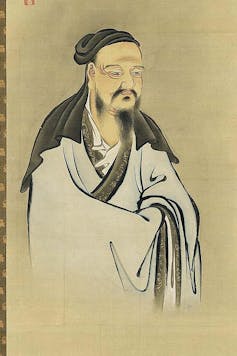

Confucius painted by Kano Yôsen'in Korenobu (Japanese, 1753–1808).

Fenollosa-Weld Collection/Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Confucius painted by Kano Yôsen'in Korenobu (Japanese, 1753–1808).

Fenollosa-Weld Collection/Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

He worked hard to promote his ideas but won few supporters. Almost every ruler saw punishment and military force as shortcuts to greater power.

It was not until 350 years later during the reign of the Emperor Wu of Han[7] that Confucianism was installed as China’s state ideology.

But this state-sanctioned version of Confucianism was not an honest revitalisation of Confucius’ ideas. Instead, it absorbed many elements from rival schools of thought, notably legalism[8], which emerged in the latter half of China’s Warring States period (453–221 BCE). Legalism argued efficient governance relies on impersonal laws and regulations — rather than moral principles and rites.

Like most great thinkers of the Axial Age[9] between the 8th and 3rd century BCE, Confucius did not believe everyone was created equal.

Similar to Plato (born over 100 years later), Confucius believed the ideal society followed a hierarchy. When asked by Duke Jing of Qi about government, Confucius famously replied:

let the ruler be a ruler; the minister, a minister; the father, a father; the son, a son.

However it would be a superficial reading of Confucius to believe he called for unconditional obedience to rulers or superiors. Confucius advised a disciple “not to deceive the ruler but to stand up to them”.

Confucius believed the legitimacy of a regime fundamentally relies on the confidence of the people. A ruler should tirelessly work hard and “lead by example”.

Like in a family, a good son listens to his father, and a good father wins respect not by imposing force or seniority but by offering heartfelt love, support, guidance and care.

In other words, Confucius saw a mutual relationship between the ruler and the ruled.

Love and respect for social harmony

To Confucius, the appropriate relations between family members are not merely metaphors for ideal political orders, but the basic fabrics of a harmonious society.

An essential family value in Confucius’ ideas is xiao 孝, or filial piety, a concept explained in at least 15 different ways in the Analects, a collection of the words from Confucius and his followers.

Read more: Can Ne Zha, the Chinese superhero with $1b at the box office, teach us how to raise good kids?[10]

Depending on the context, Confucius defined filial piety as respecting parents, as “never diverging” from parents, as not letting parents feel unnecessary anxiety, as serving parents with etiquette when they are alive, and as burying and commemorating parents with propriety after they pass away.

Confucius expected rulers to exemplify good family values. When Ji Kang Zi, the powerful prime minister of Confucius’ home state of Lu asked for advice on keeping people loyal to the realm, Confucius responded by asking the ruler to demonstrate filial piety and benignity (ci 慈).

The first leaf to ‘Song Album of The Classic of Filial Piety in Painting and Calligraphy,’ with Confucius seated at centre. Calligraphy and painting by Gaozong (1107-1187) and Ma Hezhi (c.1130-c.1170), Song dynasty.

National Palace Museum

The first leaf to ‘Song Album of The Classic of Filial Piety in Painting and Calligraphy,’ with Confucius seated at centre. Calligraphy and painting by Gaozong (1107-1187) and Ma Hezhi (c.1130-c.1170), Song dynasty.

National Palace Museum

Confucius viewed moral and ethical principles not merely as personal matters, but as social assets. He profoundly believed social harmony ultimately relies on virtuous citizens rather than sophisticated institutions.

In the ideas of Confucius, the most important moral principle is ren 仁, a concept that can hardly be translated into English without losing some of its meaning.

Like filial piety, ren is manifested in the love and respect one has for others. But ren is not restricted among family members and does not rely on blood or kinship. Ren guides people to follow their conscience. People with ren have strong compassion and empathy towards others.

Translators arguing for a single English equivalent for ren have attempted to interpret the concept as “benevolence”, “humanity”, “humanness” and “goodness”, none of which quite capture the full significance of the term.

The challenge in translating ren is not a linguistic one. Although the concept appears more than 100 times in the Analects, Confucius did not give one neat definition. Instead, he explained the term in many different ways.

As summarised by China historian Daniel Gardner[11], Confucius defined ren as:

to love others, to subdue the self and return to ritual propriety, to be respectful, tolerant, trustworthy, diligent, and kind, to be possessed of courage, to be free from worry, or to be resolute and firm.

Instead of searching for an explicit definition of ren, it is perhaps wise to view the concept as an ideal type of the highest and ultimate virtue Confucius believed good people should pursue.

Relevance in contemporary China

Confucius’ thinking hs had a profound impact on almost every great Chinese thinker since. Based upon his ideas, Mencius[12] (372–289 BCE) and Xunzi[13] (c310–c235 BCE) developed different schools of thought within the system of Confucianism.

Arguing against these ideas, Mohism[14] (4th century BCE), Daoism[15] (4th century BCE), Legalism[16] (3rd century BCE) and many other influential systems of thought emerged in the 400 years after Confucius’ time, going on to shape many aspects of the Chinese civilisation in the last two millennia.

Modern China has a complicated relationship with Confucius and his ideas.

Since the early 20th century, many intellectuals influenced by western thought started denouncing Confucianism as the reason for China’s national humiliations since the first Opium War[17] (1839-42).

Confucius received fierce criticism from both liberals and Marxists[18].

Hu Shih[19], a leader of China’s New Culture Movement in the 1910s and 1920s and an alumnus of Columbia University[20], advocated overthrowing the “House of Confucius”.

Mao Zedong, the founder of the People’s Republic of China, also repeatedly denounced Confucius and Confucianism. Between 1973 and 1975, Mao devoted the last political campaign in his life[21] against Confucianism.

Read more: To make sense of modern China, you simply can't ignore Marxism[22]

Despite these fierce criticisms and harsh persecutions, Confucius’ ideas remain in the minds and hearts of many Chinese people, both in and outside China.

One prominent example is PC Chang[23], another Chinese alumnus of Columbia University, who was instrumental in drafting the Universal Declaration of Human Rights[24], proclaimed by the United Nations General Assembly in Paris on December 10 1948. Thanks to Chang’s efforts[25], the spirit of some most essential Confucian ideas, such as ren, was deeply embedded in the Declaration.

The first session of the drafting committee on International Bill of Rights, Commission on Human Rights, at Lake Success, New York, on Monday, 9 June 1947. Dr PC Chang was vice president of the committee, and is seated second from left.

United Nations/flickr, CC BY-NC-ND[26]

The first session of the drafting committee on International Bill of Rights, Commission on Human Rights, at Lake Success, New York, on Monday, 9 June 1947. Dr PC Chang was vice president of the committee, and is seated second from left.

United Nations/flickr, CC BY-NC-ND[26]

Today, many Chinese parents, as well as the Chinese state, are keen children be provided a more Confucian education[27].

In 2004, the Chinese government named its initiative of promoting language and culture overseas[28] after Confucius, and its leadership has been enthusiastically embracing Confucius’ lessons[29] to consolidate their legitimacy and ruling in the 21st century.

Read more: Explainer: what are Confucius Institutes and do they teach Chinese propaganda?[30]

References

- ^ Kang Youwei (www.britannica.com)

- ^ highly valued among young people in China (www.scmp.com)

- ^ some doubts (theconversation.com)

- ^ Australian politics (theconversation.com)

- ^ social matters (theconversation.com)

- ^ asserted (twitter.com)

- ^ Emperor Wu of Han (en.wikipedia.org)

- ^ legalism (plato.stanford.edu)

- ^ Axial Age (www.britannica.com)

- ^ Can Ne Zha, the Chinese superhero with $1b at the box office, teach us how to raise good kids? (theconversation.com)

- ^ summarised by China historian Daniel Gardner (www.veryshortintroductions.com)

- ^ Mencius (plato.stanford.edu)

- ^ Xunzi (plato.stanford.edu)

- ^ Mohism (plato.stanford.edu)

- ^ Daoism (plato.stanford.edu)

- ^ Legalism (plato.stanford.edu)

- ^ the first Opium War (en.wikipedia.org)

- ^ Marxists (theconversation.com)

- ^ Hu Shih (www.chinaheritagequarterly.org)

- ^ an alumnus of Columbia University (c250.columbia.edu)

- ^ the last political campaign in his life (www.jstor.org)

- ^ To make sense of modern China, you simply can't ignore Marxism (theconversation.com)

- ^ PC Chang (www.upenn.edu)

- ^ Universal Declaration of Human Rights (www.un.org)

- ^ efforts (www.webpages.uidaho.edu)

- ^ CC BY-NC-ND (creativecommons.org)

- ^ a more Confucian education (www.economist.com)

- ^ its initiative of promoting language and culture overseas (theconversation.com)

- ^ enthusiastically embracing Confucius’ lessons (usa.chinadaily.com.cn)

- ^ Explainer: what are Confucius Institutes and do they teach Chinese propaganda? (theconversation.com)