When COVID is behind us, Australians are going to have to pay more tax

- Written by Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

The biggest unstated message from the intergenerational report[1] released during the lull between lockdowns is that we will need more tax.

Not now. At the moment it’s a matter of throwing everything we’ve got at getting on top of the COVID outbreaks and worrying about how to (and the extent to which we will need to) pay for it later.

But when the economy is healthy again, taxes are going to have to rise, big time.

That the intergenerational report doesn’t say so explicitly might be because the government is sticking with its arbitrary and implausible guarantee that tax collections will never climb above 23.9% of GDP[2], which is the average between the introduction of the goods and services tax and the global financial crisis.

Or it might be because what’s needed sits oddly with legislated high-end tax cuts likely to cost $17 billion[3] per year from 2024-25.

Among the drivers of increased government spending identified by the report is spending on health, at present 4.6% of gross domestic product, and on the report’s projections set to climb to 6.2% over the next 40 years.

We’ll want better health

To fund that alone the government will need to collect 6% more tax in 2061 than had spending on health stayed where it was as a proportion of GDP.

Perhaps surprisingly, most of the extra spending on health won’t be a direct result of the population ageing. It’ll be because health technologies are getting better and becoming much, much more expensive (à la the COVID vaccines). And because incomes are rising.

Rising incomes, the report explains, are the largest driver of government spending on health internationally.

That’s because for some things, including the provision of hospitals, private spending can’t cut it, no matter how well off you are.

Australia’s richest man needed hospitals as much as anyone.

AP

Australia’s richest man needed hospitals as much as anyone.

AP

After billionaire Kerry Packer suffered a massive heart attack while playing polo in 1990, he was rushed to Sydney’s Liverpool Hospital.

When the ANU election survey began in 1990, 54% of Australians surveyed regarded health as “extremely important” in determining their vote. It’s now 70%. In 1990 11% regarded health as “not very important”. It’s now just 2%[4].

The intergenerational report has spending on aged care climbing from 1.2% to 2.1% of GDP, which by itself means the tax take will have to be 4% higher than otherwise, but it was prepared ahead of the government’s final response to the aged care royal commission.

The interim response had 14 (mostly expensive) recommendations subject to “further consideration[5]”.

The National Disability Insurance Scheme already accounts for one in 20 tax dollars collected and is set to overtake Medicare.

The report says the government’s response to the royal commission into disability care presently underway is likely to place “additional pressure” on costs.

We’ll need to spend more than projected

None of this extra spending is bad if it delivers value for money, and it’s what the public wants. But it is hard to reconcile with official projections in the report showing government spending climbing only 2.5% per year in real terms over the next 40 years, compared to 3.4% per year in the past 40.

Read more: Intergenerational report to show Australia older, smaller, in debt[6]

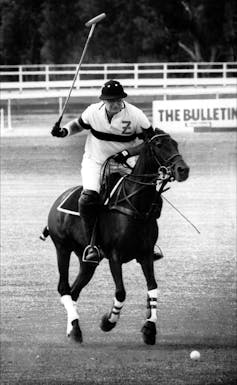

The report gets there in part by an outrageous sleight of hand. It says JobSeeker and other payments will become tiny as a proportion of GDP because they will only climb with inflation (which is typically low) rather than wage growth or GDP growth (which is typically higher, and lines up with how the pension grows).

A moment’s reflection would show that if that actually happened for 40 years — which is what the treasury’s report assumes — JobSeeker would fall from 70% of the single age pension to a hard-to-justify 40%.

JobSeeker and age pension as projected in intergenerational report

Payment for a single person, dollars per fortnight. JobSeeker indexed to IGR inflation projections, pension indexed to IGR wage projections.

Payment for a single person, dollars per fortnight. JobSeeker indexed to IGR inflation projections, pension indexed to IGR wage projections.

We know it won’t happen because it hasn’t happened.

JobSeeker was boosted this year after only 20 years[7] rather than 40 in order to make sure that sort of thing wouldn’t happen.

And we know there’s nothing to stop an intergenerational report using more realistic assumptions.

The 2015 report, released at a time when the Abbott government planned to adjust the pension in line with the more miserly JobSeeker formula, relaxed the assumption after 13 years[8] because if it left it in place the pension would slide untenably below community expectations.

We’ll easily be able to afford more tax

There’s nothing wrong with paying more tax if it’s for things we want, like better health care, better aged care, better disability care and benefits we can live on.

The intergenerational report has government spending climbing by four percentage points of GDP between now and 2061. But it also has real GDP per person almost doubling, climbing 80%.

Even if that’s an overestimate and GDP per person grows by, say, 50%, and the need for tax grows by more than four points, we’ll easily be able to afford the extra tax, and we’ll want what that tax will buy. Expectations climb with income.

The present government will be long gone by the time the tax to GDP ratio reaches its “cap” of 23.9% of GDP (which the report expects in 2035).

Mathias Cormann has moved to the OECD where average tax rates are high.

Ian Langsdon/EPA

Mathias Cormann has moved to the OECD where average tax rates are high.

Ian Langsdon/EPA

The finance minister who came up with the cap, Mathias Cormann[9], is now head of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, in which the average tax take is 34%[10] of GDP.

An obvious place to look for the tax is high-income senior citizens, at present enjoying tax-free super, refundable franking credits[11] and special tax offsets.

Grattan Institute calculations suggest an older household earning $100,000 pays less than half[12] the tax of a working-age household on the same amount.

Like the households of less well-off seniors, those households are highly likely to use the services tax provides.

To say we’ll need more tax is not to say the government needs to fund all of its spending with tax.

It is projecting budget deficits for the next 40 years[13]. Budgets have been in deficit for all but a few of the past 100 years[14].

But it will need to cover much of it with tax to keep the economy in check. If we want what tax provides, we’ll be prepared to pay it.

References

- ^ intergenerational report (treasury.gov.au)

- ^ 23.9% of GDP (www.afr.com)

- ^ $17 billion (www.smh.com.au)

- ^ 2% (australianelectionstudy.org)

- ^ further consideration (www.health.gov.au)

- ^ Intergenerational report to show Australia older, smaller, in debt (theconversation.com)

- ^ 20 years (theconversation.com)

- ^ 13 years (treasury.gov.au)

- ^ Mathias Cormann (www.skynews.com.au)

- ^ 34% (data.oecd.org)

- ^ refundable franking credits (theconversation.com)

- ^ less than half (theconversation.com)

- ^ 40 years (theconversation.com)

- ^ past 100 years (theconversation.com)

Authors: Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University