Are low interest rates increasing inequality? No, says the world's central bank

- Written by John Hawkins, Senior Lecturer, Canberra School of Politics, Economics and Society and NATSEM, University of Canberra

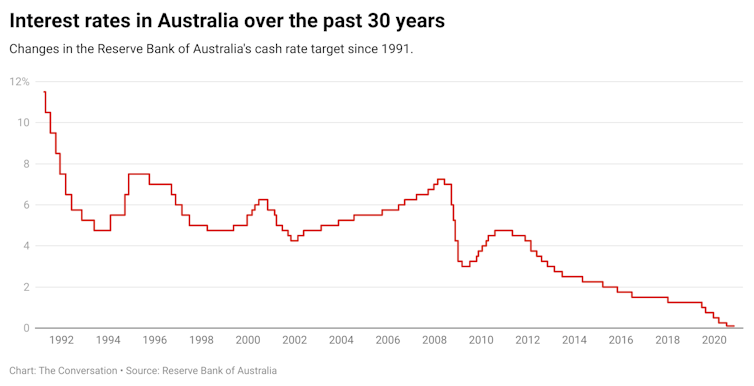

Phillip Lowe, the governor of the Reserve Bank of Australia, gets many letters and emails from retirees complaining they can’t live on the interest from their savings when interest rates are so low.

“I read these letters, many of them are very heartfelt and I feel very bad for the people who are in this situation,” he told[1] the House of Representatives standing committee on economics in February. “So I try and say we understand. The second thing I do is explain why we’re in this situation.”

Low interest rates have other critics.

The idea that central banks have increased wealth inequality by keeping interest rates so low is so widespread[2] that the central bank for central banks, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), has addressed the issue in its 2021 annual economic report[3].

The argument goes like this.

Low interest rates means potential buyers can afford to borrow more. This pushes up the price of houses. Low interest rates also encourage spending rather than saving, which contributes more to company profits and thus more dividends for shareholders. This increases the value of shares.

These factors benefit those who can afford to own property and shares. So the rich get richer.

CC BY-SA[4]

Some studies support this argument. The Netherlands’ central bank, for example, published a report in 2019[5] analysing almost a century of data for 12 advanced economies. It concluded low interest rates increased the income share of the top 1%.

RBA research published in February 2020[6] also found low interest rates increase housing wealth inequality, by bumping up the value of more expensive homes. Lowe’s deputy, Guy Debelle, acknowledged the “distributional consequences” of rising house prices in a speech in May[7], though said this wasn’t the RBA’s problem to fix.

So what is the the view of the BIS, the global expert on monetary policy?

It agrees the gap between the rich and the poor within countries has indeed widened since about the 1980s, and the COVID recession has made things worse. But it concludes low interest rates are not the real culprit.

Read more:

Vital signs: to fix Australia's housing affordability crisis, negative gearing must go[8]

Blame technology and globalisation

The BIS report instead emphasises the impact of technological progress and globalisation.

Technological progress, particularly in information technology, has increased the productivity and incomes of the wealthy (such as top lawyers and tech company executives). It has done little for many low income earners (such as aged care workers and restaurant staff).

Globalisation refers to the increased international trade of goods, and increasingly services. An example is corporations moving their call centres to countries where wages are lower. This has increased profitability for shareholders but eroded the bargaining power of lower skilled workers and small businesses.

A central bank can only do so much to mitigate these factors.

Interest rates and jobs

The main thing it can do is to help minimise unemployment, perhaps the most important driver of income inequality. Its tool to stimulate the economy is lower interest rates.

Lower rates means consumers have less reason to save, so they spend more. Businesses are more likely to borrow to invest. All this helps create more jobs. So higher rates would likely mean higher unemployment, making income inequality worse.

As Lowe explains to retirees: “Those people who have a job might be a child or your grandchild and the society, in the end, as a collective, is going to be better off if more people have jobs.”

CC BY-SA[4]

Some studies support this argument. The Netherlands’ central bank, for example, published a report in 2019[5] analysing almost a century of data for 12 advanced economies. It concluded low interest rates increased the income share of the top 1%.

RBA research published in February 2020[6] also found low interest rates increase housing wealth inequality, by bumping up the value of more expensive homes. Lowe’s deputy, Guy Debelle, acknowledged the “distributional consequences” of rising house prices in a speech in May[7], though said this wasn’t the RBA’s problem to fix.

So what is the the view of the BIS, the global expert on monetary policy?

It agrees the gap between the rich and the poor within countries has indeed widened since about the 1980s, and the COVID recession has made things worse. But it concludes low interest rates are not the real culprit.

Read more:

Vital signs: to fix Australia's housing affordability crisis, negative gearing must go[8]

Blame technology and globalisation

The BIS report instead emphasises the impact of technological progress and globalisation.

Technological progress, particularly in information technology, has increased the productivity and incomes of the wealthy (such as top lawyers and tech company executives). It has done little for many low income earners (such as aged care workers and restaurant staff).

Globalisation refers to the increased international trade of goods, and increasingly services. An example is corporations moving their call centres to countries where wages are lower. This has increased profitability for shareholders but eroded the bargaining power of lower skilled workers and small businesses.

A central bank can only do so much to mitigate these factors.

Interest rates and jobs

The main thing it can do is to help minimise unemployment, perhaps the most important driver of income inequality. Its tool to stimulate the economy is lower interest rates.

Lower rates means consumers have less reason to save, so they spend more. Businesses are more likely to borrow to invest. All this helps create more jobs. So higher rates would likely mean higher unemployment, making income inequality worse.

As Lowe explains to retirees: “Those people who have a job might be a child or your grandchild and the society, in the end, as a collective, is going to be better off if more people have jobs.”

Reserve Bank of Australia governor Philip Low addresses the House of Representatives standing committee on economics, February 5 2021.

Lukas Coch/AAP

Tweaking monetary policy

Concerns about inequality may be one reason some central banks have altered their monetary policy framework. They are giving more priority to reducing unemployment and showing a willingness to tolerate temporarily higher inflation (which central banks control by raising interest rates).

The US Federal Reserve, for example, has said it will tolerate a period of inflation above its long-term target[9].

The RBA has more subtly done something similar.

Lowe has said[10] Austrlia’s central bank will not increase interest rates until actual inflation is back within the target range. Previously it would have acted pre-emptively based on forecast inflation, given the lags between its actions and the impact on economic behaviour.

Waiting does carry some risk that inflation will temporarily overshoot its target in 2024 or 2025. But with inflation having been below its target for an extended period, it is willing to accept this.

Other ways to reduce inequality

Central banks may be able to help reduce inequality through some of their other roles, however.

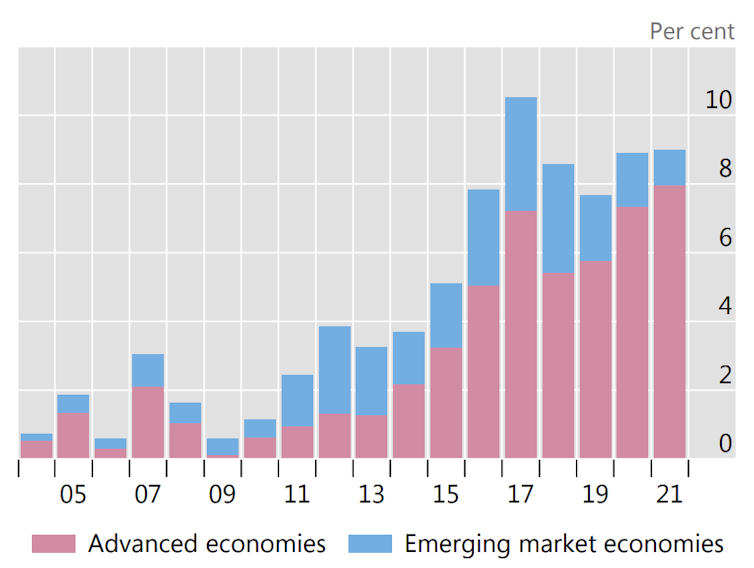

They can use their profile to advocate for policies that will help lower unemployment. Indeed the Bank for International Settlements’ report notes the proportion of speeches by central bankers that mention inequality and the “distributional consequences” of monetary policy have risen significantly over the past decade.

Reserve Bank of Australia governor Philip Low addresses the House of Representatives standing committee on economics, February 5 2021.

Lukas Coch/AAP

Tweaking monetary policy

Concerns about inequality may be one reason some central banks have altered their monetary policy framework. They are giving more priority to reducing unemployment and showing a willingness to tolerate temporarily higher inflation (which central banks control by raising interest rates).

The US Federal Reserve, for example, has said it will tolerate a period of inflation above its long-term target[9].

The RBA has more subtly done something similar.

Lowe has said[10] Austrlia’s central bank will not increase interest rates until actual inflation is back within the target range. Previously it would have acted pre-emptively based on forecast inflation, given the lags between its actions and the impact on economic behaviour.

Waiting does carry some risk that inflation will temporarily overshoot its target in 2024 or 2025. But with inflation having been below its target for an extended period, it is willing to accept this.

Other ways to reduce inequality

Central banks may be able to help reduce inequality through some of their other roles, however.

They can use their profile to advocate for policies that will help lower unemployment. Indeed the Bank for International Settlements’ report notes the proportion of speeches by central bankers that mention inequality and the “distributional consequences” of monetary policy have risen significantly over the past decade.

Proportion of speeches by central bankers mentioning ‘inequality’ and ‘distributional consequences/impact of monetary policy’.

Bank for International Settlements, CC BY-SA[11]

The RBA has argued strongly[12] that expansionary fiscal policy – that is, government spending – is important to keep the economy on track. Public investment will encourage rather than “crowd out” private investment. This is a rejection of those who argue for a rapid return to fiscal austerity[13].

Central banks can also encourage governments to adopt policies that tend to reduce inequality over time. For example, in February Lowe supported[14] the “wide consensus in the community[15]” for higher unemployment payments.

Read more:

5 ways the Reserve Bank is going to bat for Australia like never before[16]

Central banks can also reduce inequality by promoting financial inclusion, including for Indigenous citizens[17]. They can help develop a more efficient payments system. All these sorts of measures help the poor. Again the RBA has been acting on these fronts.

Inequality of incomes is an important issue. But on balance low interest rates are moderating rather than exacerbating it.

Proportion of speeches by central bankers mentioning ‘inequality’ and ‘distributional consequences/impact of monetary policy’.

Bank for International Settlements, CC BY-SA[11]

The RBA has argued strongly[12] that expansionary fiscal policy – that is, government spending – is important to keep the economy on track. Public investment will encourage rather than “crowd out” private investment. This is a rejection of those who argue for a rapid return to fiscal austerity[13].

Central banks can also encourage governments to adopt policies that tend to reduce inequality over time. For example, in February Lowe supported[14] the “wide consensus in the community[15]” for higher unemployment payments.

Read more:

5 ways the Reserve Bank is going to bat for Australia like never before[16]

Central banks can also reduce inequality by promoting financial inclusion, including for Indigenous citizens[17]. They can help develop a more efficient payments system. All these sorts of measures help the poor. Again the RBA has been acting on these fronts.

Inequality of incomes is an important issue. But on balance low interest rates are moderating rather than exacerbating it.

References

- ^ he told (parlinfo.aph.gov.au)

- ^ so widespread (www.youtube.com)

- ^ 2021 annual economic report (www.bis.org)

- ^ CC BY-SA (creativecommons.org)

- ^ report in 2019 (www.dnb.nl)

- ^ research published in February 2020 (www.rba.gov.au)

- ^ a speech in May (www.rba.gov.au)

- ^ Vital signs: to fix Australia's housing affordability crisis, negative gearing must go (theconversation.com)

- ^ it will tolerate a period of inflation above its long-term target (www.federalreserve.gov)

- ^ said (www.rba.gov.au)

- ^ CC BY-SA (creativecommons.org)

- ^ argued strongly (www.rba.gov.au)

- ^ fiscal austerity (www.researchgate.net)

- ^ supported (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ wide consensus in the community (assets.boardroom.media)

- ^ 5 ways the Reserve Bank is going to bat for Australia like never before (theconversation.com)

- ^ Indigenous citizens (www.rba.gov.au)

Authors: John Hawkins, Senior Lecturer, Canberra School of Politics, Economics and Society and NATSEM, University of Canberra