Behind moves to regulate breastmilk trade lies the threat of a corporate takeover

- Written by Julie P. Smith, Honorary Associate Professor, Australian National University

The European Union is preparing to harmonise regulations governing the trade in human milk[1], which sounds like a good thing. But it won’t be if it sidelines breastfeeding or makes informal human-to-human milk exchanges more difficult.

Women and their families have exchanged human milk informally[2] (including for money) throughout history, and still do.

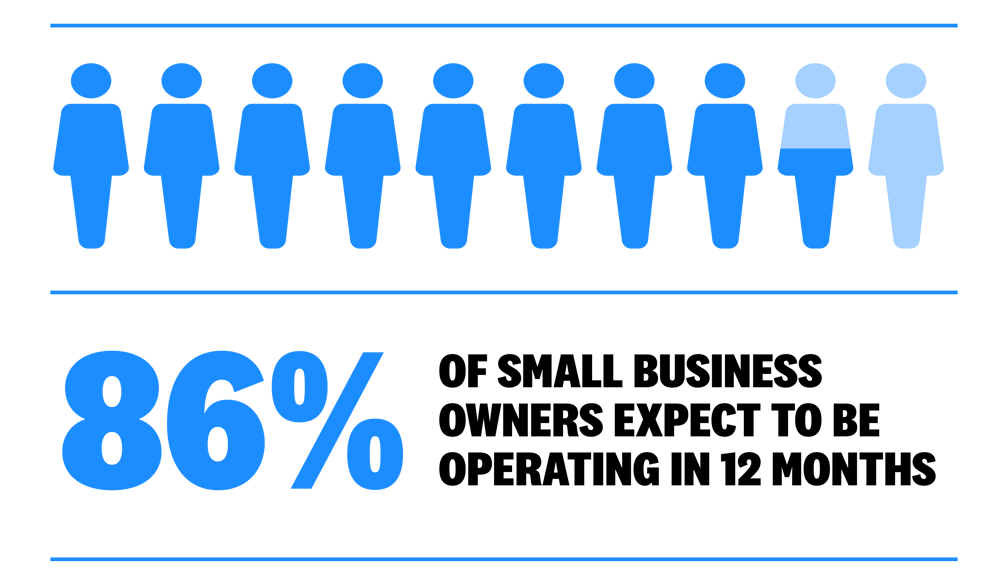

Until a century ago human milk was mainly delivered in person[3], breast-to-child, by friends, relatives or wet nurses if mothers couldn’t provide it.

Woman buying milk from nurse at counter, 1939.

AP-HP Archives, 3Fi3_25_MATERNITE _092

Woman buying milk from nurse at counter, 1939.

AP-HP Archives, 3Fi3_25_MATERNITE _092

As the paediatric profession developed, hospitals in Europe and the United States took over the process and began administering human milk by bottles, at first filled by volunteers, and later, in the lead-up to the second world war, by paid donors[4].

Higher women’s wages after the war made paying donors financially prohibitive, and most countries moved closer to a “gift economy[5]” in which payment for products such as human milk and blood was seen as inappropriate[6], alongside a growing commercial market for formula and powder derived from cows milk.

Donor milk collected by charities and non-profit organisations from screened donors is mostly pasteurised[7] and tested to minimise risks of disease.

Biotech discovers breast milk

Things changed in 1999 when an American company, Prolacta[8], developed human milk-based products for fortifying breast milk fed to premature infants.

At first Prolacta didn’t pay[9] donors, but it now pays about US$4[10] per 100ml for milk it uses to make products that sell for up to US$250[11] per 100 ml.

Prolacta human milk products[12]

In 2015 a not-for-profit Utah-based company, Ambrosia Labs[13] established clinics in Cambodia to collect milk for exporting to the United States.

After the United Nations Children’s Fund condemned the practice saying breast milk could be considered “human tissue” the Cambodian government banned[14] it. Some mothers despaired at losing crucial income[15].

Read more:

Without better regulation, the market for breast milk will exploit mothers[16]

A few years later in 2017 an Australian-Indian company Neolacta[17], was granted permission to sell milk collected from Indian mothers[18] in Australia.

In 2019 a related company, NeoKare[19], established a “state-of-the-art” plant in Europe making freeze-dried fortifier sourced from UK donors.

These human milk product manufacturers are competing with cow-sourced product manufacturers such as Nestle and might soon be competing with start-ups growing new products that mimic human milk[20].

Industry backs new regulation

The harmonisation being considered by the European Union would extend to human milk the rules that already govern trade in blood, tissues and cells.

Some member states in the European Union already apply tissue and cell rules to human milk, others apply food legislation, and at least 11 don’t regulate it at all[21].

Australian regulators will be watching closely, because Australian states and territories have similarly diverse rules.

That formula companies[22] are backing the idea provides cause for concern.

But it’s women who matter

Health authorities have already expressed disquiet[23] about commerce-free internet-based milk sharing. The proposal would give them greater powers to act against it.

If these powers were applied heavily they could shut down the generally safe[24] and self-regulated human-to-human trade.

And advancing the medical market for human milk products might delay the advances in social and employment protection policies needed to support breastfeeding at work, at home and in public.

Prolacta human milk products[12]

In 2015 a not-for-profit Utah-based company, Ambrosia Labs[13] established clinics in Cambodia to collect milk for exporting to the United States.

After the United Nations Children’s Fund condemned the practice saying breast milk could be considered “human tissue” the Cambodian government banned[14] it. Some mothers despaired at losing crucial income[15].

Read more:

Without better regulation, the market for breast milk will exploit mothers[16]

A few years later in 2017 an Australian-Indian company Neolacta[17], was granted permission to sell milk collected from Indian mothers[18] in Australia.

In 2019 a related company, NeoKare[19], established a “state-of-the-art” plant in Europe making freeze-dried fortifier sourced from UK donors.

These human milk product manufacturers are competing with cow-sourced product manufacturers such as Nestle and might soon be competing with start-ups growing new products that mimic human milk[20].

Industry backs new regulation

The harmonisation being considered by the European Union would extend to human milk the rules that already govern trade in blood, tissues and cells.

Some member states in the European Union already apply tissue and cell rules to human milk, others apply food legislation, and at least 11 don’t regulate it at all[21].

Australian regulators will be watching closely, because Australian states and territories have similarly diverse rules.

That formula companies[22] are backing the idea provides cause for concern.

But it’s women who matter

Health authorities have already expressed disquiet[23] about commerce-free internet-based milk sharing. The proposal would give them greater powers to act against it.

If these powers were applied heavily they could shut down the generally safe[24] and self-regulated human-to-human trade.

And advancing the medical market for human milk products might delay the advances in social and employment protection policies needed to support breastfeeding at work, at home and in public.

Australian Breastfeeding Association[25]

Human milk is not simply a homogenised “commodity crop in a bottle”.

Breastfeeding creates connections that are important for women’s health and wellbeing[26] and for their babies[27].

Ironically, where governments fail[28] to adequately protect, promote and support breastfeeding, mothers are often forced to turn to commercial formula for a quick fix.

The proposals as drafted[29] pay scant regard to the United Nations human rights commissioner’s[30] view that “states should do more to support and protect breastfeeding, and end inappropriate marketing of breast-milk substitutes”.

A truly comprehensive set of laws would include protection from marketing and biomedical experiments[31] and allow suitable recompense for donors. Serological testing would be easily available to donors along with guidance to support milk sharing outside of medical facilities.

Read more:

The rise of commercial milk formulas matters for women and children[32]

Such comprehensive laws would impose levies on commercial substitutes in order to fund better breastfeeding support[33] in maternity and newborn facilities.

They would have at their centre the needs and rights of women, who are both the main providers of human milk and (on their children’s behalf) its biggest users.

Australian Breastfeeding Association[25]

Human milk is not simply a homogenised “commodity crop in a bottle”.

Breastfeeding creates connections that are important for women’s health and wellbeing[26] and for their babies[27].

Ironically, where governments fail[28] to adequately protect, promote and support breastfeeding, mothers are often forced to turn to commercial formula for a quick fix.

The proposals as drafted[29] pay scant regard to the United Nations human rights commissioner’s[30] view that “states should do more to support and protect breastfeeding, and end inappropriate marketing of breast-milk substitutes”.

A truly comprehensive set of laws would include protection from marketing and biomedical experiments[31] and allow suitable recompense for donors. Serological testing would be easily available to donors along with guidance to support milk sharing outside of medical facilities.

Read more:

The rise of commercial milk formulas matters for women and children[32]

Such comprehensive laws would impose levies on commercial substitutes in order to fund better breastfeeding support[33] in maternity and newborn facilities.

They would have at their centre the needs and rights of women, who are both the main providers of human milk and (on their children’s behalf) its biggest users.

References

- ^ human milk (ec.europa.eu)

- ^ informally (dl.uswr.ac.ir)

- ^ in person (internationalbreastfeedingjournal.biomedcentral.com)

- ^ paid donors (academic.oup.com)

- ^ gift economy (www.tandfonline.com)

- ^ inappropriate (www.routledge.com)

- ^ pasteurised (internationalbreastfeedingjournal.biomedcentral.com)

- ^ Prolacta (www.prolacta.com)

- ^ didn’t pay (www.thecut.com)

- ^ US$4 (www.prolacta.com)

- ^ US$250 (www.nature.com)

- ^ Prolacta human milk products (www.prolacta.com)

- ^ Ambrosia Labs (www.bodyandsoul.com.au)

- ^ banned (www.smh.com.au)

- ^ crucial income (www.phnompenhpost.com)

- ^ Without better regulation, the market for breast milk will exploit mothers (theconversation.com)

- ^ Neolacta (neolacta.com)

- ^ Indian mothers (www.abc.net.au)

- ^ NeoKare (neokare.co.uk)

- ^ mimic human milk (www.theatlantic.com)

- ^ don’t regulate it at all (ec.europa.eu)

- ^ formula companies (www.efcni.org)

- ^ disquiet (internationalbreastfeedingjournal.biomedcentral.com)

- ^ safe (pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- ^ Australian Breastfeeding Association (www.breastfeeding.asn.au)

- ^ health and wellbeing (onlinelibrary.wiley.com)

- ^ babies (onlinelibrary.wiley.com)

- ^ where governments fail (internationalbreastfeedingjournal.biomedcentral.com)

- ^ as drafted (ec.europa.eu)

- ^ human rights commissioner’s (www.ohchr.org)

- ^ biomedical experiments (www.diva-portal.org)

- ^ The rise of commercial milk formulas matters for women and children (theconversation.com)

- ^ breastfeeding support (www.who.int)

Authors: Julie P. Smith, Honorary Associate Professor, Australian National University