To get ahead as an introvert, act like an extravert. It's not as hard as you think

- Written by Andrew Spark, Postdoctoral research fellow, Queensland University of Technology

Leadership is a human universal[1]. It can even be seen in other species, which suggests it may be an evolutionarily ancient process[2].

A common personality trait of “natural” leaders is a higher than average level of extraversion. Research[3] consistently shows extraverts, compared with introverts, are more likely to be regarded as leaders by others, and more likely to obtain leadership roles.

We decided to run an experiment[4] to see if we could turn the leadership tables around by getting introverts to act like extraverts. We also wanted to find out how acting like an extravert makes introverts feel about themselves.

Our results show[5] that introverts who act like extraverts are indeed viewed by others as having more leadership potential. We also found no evidence of psychological costs for introverts.

What we know about extraversion and leadership

Before we get to the specifics of our research, let’s briefly recap the basic science of extraversion and leadership.

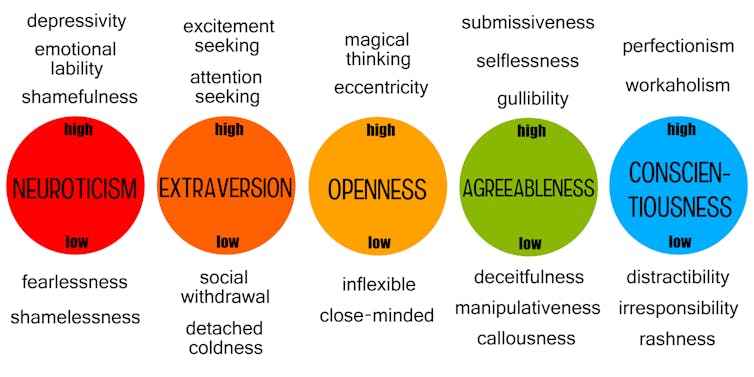

Extraversion is a continuum that measures the degree to which someone is enthusiastic, assertive and seeks out social interaction. It is typically included as part of the five-factor model[6] of personality.

The other dimensions – or traits – in the five-factor model include openness (being intellectually curious and creative), conscientiousness (being orderly and industrious), agreeableness (being compassionate and polite), and neuroticism (being sensitive to experiencing negative emotions like anxiety, depression, and anger).

The big five personality traits.

Shutterstock

The big five personality traits.

Shutterstock

Extraversion has biological roots and is heritable. In others words, part of the reason we find differences in levels of extraversion between people is because there are genetic differences[7] between people that partially determine our personality. Our genes even predict the likelihood we will occupy a leadership position[8].

We also know that extraverts have a more sensitive dopamine system[9] in their brain. They are wired to find rewards more enticing. They crave social interaction and the attention that comes with it[10]. This fact may partially explain why extraverts are more motivated[11] to obtain leadership roles, given leadership is an inherently social process.

Read more: It's hard to find a humble CEO. Here's why[12]

How we did our experiment

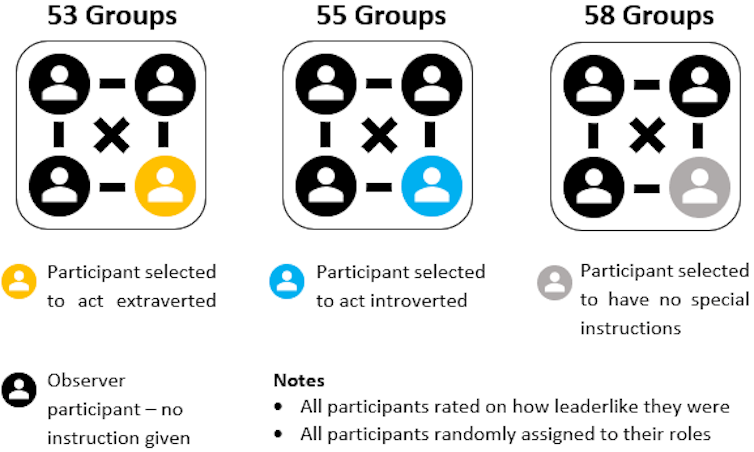

Our experiment[13] consisted of 601 participants randomly divided into 166 leaderless groups of typically four people.

We asked these groups to complete a 20-minute joint problem-solving activity (prioritising items needed to survive on the Moon). Participants were not told the purpose of the experiment.

We then split the groups into three “experimental conditions”.

In the first (consisting of 53 groups) we randomly selected one person per group to act energetic, talkative, enthusiastic, bold, active, assertive and sociable – in other words, extraverted. These instructions were not known to other group members.

In the second (55 groups), the randomly chosen group member was secretly instructed to act quiet, reserved, lethargic, passive, compliant and unadventurous – in other words, introverted.

The third was our control condition with 58 groups, where no individual instructions were given.

At the of end the activity, participants rated the leadership quality of other group members (and themselves). They also rated how they felt.

We controlled for age, gender and other personality traits[14] using a standard personality test. This ensured we isolated the true effect of extraverted and introverted behaviour.

Acting like an extravert works

The first part of our results were unsurprising. Compared with participants in the control condition, those instructed to act extraverted were rated by others as having more leadership potential. Those instructed to act introverted were rated lower.

What was notable is that these ratings did not depend on “trait extraversion”. In other words, when instructed to act extraverted, both introverts and extraverts were rated higher on their leadership potential compared with an equivalently extraverted person in the control condition.

Equally, we found the participants instructed to act introverted were rated lower on their leadership potential compared with control participants.

But what was particularly interesting was these participants also rated themselves especially poorly on leadership ratings – worse than did their group members. Acting introverted had a particularly negative impact on how those individuals viewed their own leadership potential.

Read more:

Why too many fearless people on a team make collaboration less likely[15]

How acting out of character felt

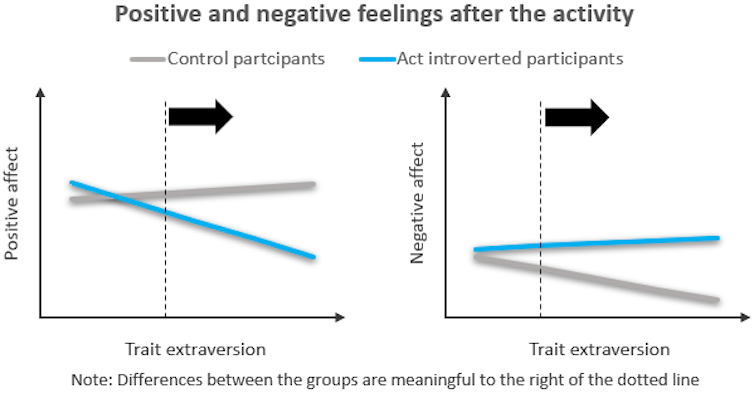

How our “actors” felt after the activity is shown in the next figure.

Compared with the control participants, there was no difference for those who acted extraverted. Even introverts felt perfectly OK after acting like extraverts.

In the first (consisting of 53 groups) we randomly selected one person per group to act energetic, talkative, enthusiastic, bold, active, assertive and sociable – in other words, extraverted. These instructions were not known to other group members.

In the second (55 groups), the randomly chosen group member was secretly instructed to act quiet, reserved, lethargic, passive, compliant and unadventurous – in other words, introverted.

The third was our control condition with 58 groups, where no individual instructions were given.

At the of end the activity, participants rated the leadership quality of other group members (and themselves). They also rated how they felt.

We controlled for age, gender and other personality traits[14] using a standard personality test. This ensured we isolated the true effect of extraverted and introverted behaviour.

Acting like an extravert works

The first part of our results were unsurprising. Compared with participants in the control condition, those instructed to act extraverted were rated by others as having more leadership potential. Those instructed to act introverted were rated lower.

What was notable is that these ratings did not depend on “trait extraversion”. In other words, when instructed to act extraverted, both introverts and extraverts were rated higher on their leadership potential compared with an equivalently extraverted person in the control condition.

Equally, we found the participants instructed to act introverted were rated lower on their leadership potential compared with control participants.

But what was particularly interesting was these participants also rated themselves especially poorly on leadership ratings – worse than did their group members. Acting introverted had a particularly negative impact on how those individuals viewed their own leadership potential.

Read more:

Why too many fearless people on a team make collaboration less likely[15]

How acting out of character felt

How our “actors” felt after the activity is shown in the next figure.

Compared with the control participants, there was no difference for those who acted extraverted. Even introverts felt perfectly OK after acting like extraverts.

The extraverts who acted introverted were a different matter. They had fewer positive and more negative feelings compared with those in the control condition. In short, acting introverted made them feel bad.

Should introverts act out of character to get ahead?

Our research shows introverts can effectively act out of character to obtain and succeed in leadership roles.

If you’re an introvert, you might feel you should not have to. But we suggest that being prepared to adapt your behaviour to the demands of a situation gives you an advantage over those who aren’t.

Nor is it as hard as you may think. Research shows introverts overestimate the unpleasantness[16] and underestimate the “hedonic benefits[17]” of acting extraverted. One study[18] even suggests introverts feel more authentic when acting extraverted.

Read more:

Introverts think they won't like being leaders but they are capable[19]

Knowing extraverted behaviour is usually[20] – though not always[21] – enjoyable can help you feel more confident about “faking” extraverted behaviour in your own best interest.

So lead on – if you want.

The extraverts who acted introverted were a different matter. They had fewer positive and more negative feelings compared with those in the control condition. In short, acting introverted made them feel bad.

Should introverts act out of character to get ahead?

Our research shows introverts can effectively act out of character to obtain and succeed in leadership roles.

If you’re an introvert, you might feel you should not have to. But we suggest that being prepared to adapt your behaviour to the demands of a situation gives you an advantage over those who aren’t.

Nor is it as hard as you may think. Research shows introverts overestimate the unpleasantness[16] and underestimate the “hedonic benefits[17]” of acting extraverted. One study[18] even suggests introverts feel more authentic when acting extraverted.

Read more:

Introverts think they won't like being leaders but they are capable[19]

Knowing extraverted behaviour is usually[20] – though not always[21] – enjoyable can help you feel more confident about “faking” extraverted behaviour in your own best interest.

So lead on – if you want.

References

- ^ human universal (psycnet.apa.org)

- ^ evolutionarily ancient process (www.sciencedirect.com)

- ^ Research (bit.ly)

- ^ experiment (www.sciencedirect.com)

- ^ results show (www.sciencedirect.com)

- ^ five-factor model (psych.colorado.edu)

- ^ genetic differences (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

- ^ leadership position (www.sciencedirect.com)

- ^ sensitive dopamine system (www.sciencedirect.com)

- ^ attention that comes with it (psycnet.apa.org)

- ^ more motivated (psycnet.apa.org)

- ^ It's hard to find a humble CEO. Here's why (theconversation.com)

- ^ experiment (www.sciencedirect.com)

- ^ personality traits (www.psychologytoday.com)

- ^ Why too many fearless people on a team make collaboration less likely (theconversation.com)

- ^ overestimate the unpleasantness (www.sciencedirect.com)

- ^ hedonic benefits (psycnet.apa.org)

- ^ One study (onlinelibrary.wiley.com)

- ^ Introverts think they won't like being leaders but they are capable (theconversation.com)

- ^ usually (psycnet.apa.org)

- ^ not always (psycnet.apa.org)

Authors: Andrew Spark, Postdoctoral research fellow, Queensland University of Technology