How job insecurity shapes your personality

- Written by Lena Wang, Senior Lecturer in Management, RMIT University

With unemployment at its highest rate in three decades, almost a million Australians[1] are experiencing the anxiety of being out of work. Even more are underemployed, and more still holding on to jobs for now, not knowing if that will last.

If you feel secure in your job, you are lucky. Because the psychological fallout of job insecurity can last a lifetime.

Read more: Winding back JobKeeper and JobSeeker will push 740,000 Australians into poverty[2]

Many studies have shown the association between employment and psychological and physical well-being. A meta-analysis of 104 empirical studies[3] by behavioural researcher Frances McKee-Ryan and colleagues argues the evidence is “strongly supportive of a causal relationship” between unemployment and mental health.

The effect of job insecurity, however, has been less researched, even though such insecurity has long been an issue for many in contract-based, casual and gig economy jobs; and it will affect many more as the threat of artificial intelligence and automation looms.

Our large-scale study[4], tracking the experience of more than a thousand Australians over nearly a decade, suggests job insecurity over a prolonged period can actually change your personality. And that could make a significant difference to your life and well-being decades down the track.

Read more: Hunger, lost income and increased anxiety: how coronavirus lockdowns put huge pressure on young people around the world[5]

How we tracked personality changes

Personality is often assumed to be stable and enduring. A growing body of research, however, shows how personalities evolve over time. For example, on average self-confidence, warmth, self-control and emotional stability tends to increase as we age, with the greatest change being between the age of 20 and 40[6].

Studies like ours are investigating how work experiences shape personality over time. Previous studies, for example, suggest more autonomy at work[7] can increases a person’s ability to cope with new and unpredictable situations. A demanding and stressful job[8], on the other hand, can make someone more neurotic and less conscientious.

To explore the possible personality effects, we used data from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia survey[9], a national survey that collects information from a large and representative sample of Australians each year. The survey tracks the same people as far as is possible, which enables researchers to look at how individual changes over time. Respondents are asked (among other things) how secure they feel their job is, as well as questions relating to personality traits.

Demanding and stressful work can make someone more neurotic and less conscientious. Shutterstock

Demanding and stressful work can make someone more neurotic and less conscientious. Shutterstock

We analysed nine years of data from 1,046 Australians working in a range of occupations and professions. Every four years (years 1, 5 and 9) participants completed a well-established personality measure[10], asking them to describe their characteristics against adjectives such as “talkative”, “moody”, “warm”, “orderly” and “creative”.

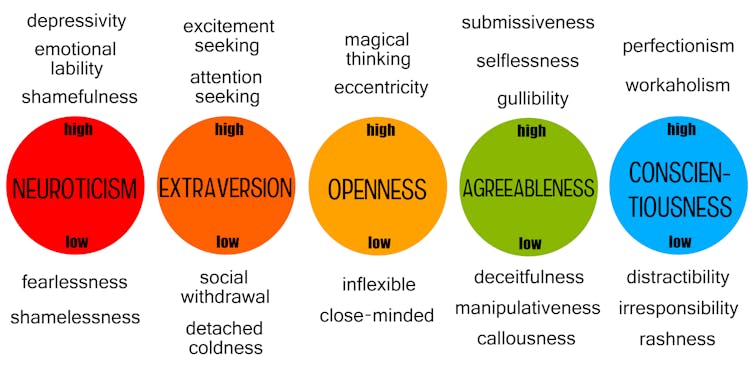

These adjectives reflect where people sit in relation to five key personality traits: neuroticism (or emotional stability), extraversion, openness, agreeableness and conscientiousness.

Shutterstock In our modelling approach, we examined how participants’ chronic job insecurity in preceding years (i.e. during years 1-4 and 5-8) predicted their personality change after this experience (i.e. during years 1-5 and 5-9). We controlled for other job characteristics (such as job autonomy and demands) to establish the specific impact of chronic job insecurity. Effects of chronic job insecurity Our analysis showed that workers who experienced job insecurity over several consecutive years became less emotionally stable, less agreeable and less conscientious. 1. Reduced emotional stability Understandably, chronic job insecurity can cause us to become anxious, tense, irritable and depressed. Job insecurity itself is already worrying, and when this goes on for a long time, it can make us feel we are trapped in that situation, unable to escape. As a result, we are likely to become more depressed and neurotic over time with obvious impacts on our personal and family relationships, as well as our professional relationships. 2. Reduced agreeableness Agreeable people are big on sympathy, cooperation and helping others. They’re the ones really good at building harmonious social relationships. But when a potential threat hangs over us for an extended period of time, chronic job insecurity can shift our focus to be more on ourselves instead of on others. This can really affect our standing as a positive and likeable team member at work, or the home. 3. Reduced conscientiousness Research shows that when we’re constantly worried about the continuity of our jobs we are likely to become less motivated to put in effort, set goals and achieve goals in a reliable way. This is bad news for those of us trying to keep motivated through tough times. It’s also bad news for who we work for. Maintaining productivity and motivation will be a massive challenge for many mangers. What this means for personality growth The three personality traits affected most severely by chronic job insecurity are those most associated with healthy personality growth. As we age and mature, we generally become more emotionally stable, more agreeable and more conscientious. Our research shows chronic job insecurity can stunt this emotional growth, interrupting the healthy mellowing of our personalities. How to save your ‘self’ None of this is very cheery. But the good news is that, apart from worrying about it, there are things you can actually do. The first step is to “know thyself” and be aware of the pitfalls, then to cultivate a growth mindset by accepting change and being open to new opportunities. Human beings have a natural tendency to perceive uncertainty in negative terms[11], which helps explain why we are prone to falling into a vicious cycle induced by unemployment and job insecurity. But such negative thinking can be mitigated through conscious awareness and deliberate practice. Read more: Struggling with the uncertainty of life under coronavirus? How Kierkegaard's philosophy can help[12] Focus on things you can control. Look for solutions rather than dwell on problems. Be willing to learn new skills or take on new tasks. Research has shown that being proactive in managing your career[13], such as plotting a career plan, actively building a network of contacts for career advice, and talking with peers and boss about future opportunities, all help to cope with insecure work conditions. Also important is to look out for each other. Support from colleagues, family and friends[14] has been found to help build resilience and confidence, mitigating the potential negative spiral of job insecurity on personality in the long run.

Shutterstock In our modelling approach, we examined how participants’ chronic job insecurity in preceding years (i.e. during years 1-4 and 5-8) predicted their personality change after this experience (i.e. during years 1-5 and 5-9). We controlled for other job characteristics (such as job autonomy and demands) to establish the specific impact of chronic job insecurity. Effects of chronic job insecurity Our analysis showed that workers who experienced job insecurity over several consecutive years became less emotionally stable, less agreeable and less conscientious. 1. Reduced emotional stability Understandably, chronic job insecurity can cause us to become anxious, tense, irritable and depressed. Job insecurity itself is already worrying, and when this goes on for a long time, it can make us feel we are trapped in that situation, unable to escape. As a result, we are likely to become more depressed and neurotic over time with obvious impacts on our personal and family relationships, as well as our professional relationships. 2. Reduced agreeableness Agreeable people are big on sympathy, cooperation and helping others. They’re the ones really good at building harmonious social relationships. But when a potential threat hangs over us for an extended period of time, chronic job insecurity can shift our focus to be more on ourselves instead of on others. This can really affect our standing as a positive and likeable team member at work, or the home. 3. Reduced conscientiousness Research shows that when we’re constantly worried about the continuity of our jobs we are likely to become less motivated to put in effort, set goals and achieve goals in a reliable way. This is bad news for those of us trying to keep motivated through tough times. It’s also bad news for who we work for. Maintaining productivity and motivation will be a massive challenge for many mangers. What this means for personality growth The three personality traits affected most severely by chronic job insecurity are those most associated with healthy personality growth. As we age and mature, we generally become more emotionally stable, more agreeable and more conscientious. Our research shows chronic job insecurity can stunt this emotional growth, interrupting the healthy mellowing of our personalities. How to save your ‘self’ None of this is very cheery. But the good news is that, apart from worrying about it, there are things you can actually do. The first step is to “know thyself” and be aware of the pitfalls, then to cultivate a growth mindset by accepting change and being open to new opportunities. Human beings have a natural tendency to perceive uncertainty in negative terms[11], which helps explain why we are prone to falling into a vicious cycle induced by unemployment and job insecurity. But such negative thinking can be mitigated through conscious awareness and deliberate practice. Read more: Struggling with the uncertainty of life under coronavirus? How Kierkegaard's philosophy can help[12] Focus on things you can control. Look for solutions rather than dwell on problems. Be willing to learn new skills or take on new tasks. Research has shown that being proactive in managing your career[13], such as plotting a career plan, actively building a network of contacts for career advice, and talking with peers and boss about future opportunities, all help to cope with insecure work conditions. Also important is to look out for each other. Support from colleagues, family and friends[14] has been found to help build resilience and confidence, mitigating the potential negative spiral of job insecurity on personality in the long run. References

- ^ almost a million Australians (www.abs.gov.au)

- ^ Winding back JobKeeper and JobSeeker will push 740,000 Australians into poverty (theconversation.com)

- ^ 104 empirical studies (psycnet.apa.org)

- ^ large-scale study (psycnet.apa.org)

- ^ Hunger, lost income and increased anxiety: how coronavirus lockdowns put huge pressure on young people around the world (theconversation.com)

- ^ 20 and 40 (journals.sagepub.com)

- ^ autonomy at work (www.sciencedirect.com)

- ^ demanding and stressful job (www.sciencedirect.com)

- ^ Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia survey (melbourneinstitute.unimelb.edu.au)

- ^ a well-established personality measure (www.tandfonline.com)

- ^ perceive uncertainty in negative terms (journals.aom.org)

- ^ Struggling with the uncertainty of life under coronavirus? How Kierkegaard's philosophy can help (theconversation.com)

- ^ being proactive in managing your career (psycnet.apa.org)

- ^ colleagues, family and friends (journals.sagepub.com)

Authors: Lena Wang, Senior Lecturer in Management, RMIT University