Time after time, tragedies like the Titan disaster occur because leaders ignore red flags

- Written by Tony Jaques, Senior Research Associate, RMIT University

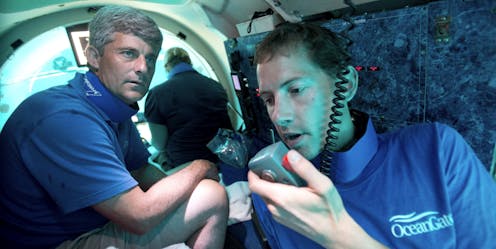

The loss of the OceanGate submersible Titan appears to be an example of warnings ignored.

“We have heard the baseless cries of ‘you are going to kill someone’ way too often,” OceanGate chief executive Stockton Rush wrote in 2018[1], after being told he was putting lives at risk using his experimental submersible Titan to ferry customers to view the wreck of the Titanic almost 4,000 metres below sea level. “I take this as a serious personal insult.”

Rush, who died along with four others with the Titan’s “catastrophic failure” last week, was warned by marine technology experts as well as atleast one employee[2] (subsequently dismissed) that the carbon-fibre vessel risked potentially “catastrophic” problems without rigorous testing and assessments.

Those boarding the Titan had to sign[3] a waiver stating it was “an experimental submersible vessel that has not been approved or certified by any regulatory body which could result in physical injury, emotional trauma or death”. That should have been warning enough.

But this is not about being wise after the event. Consulting firm Institute for Crisis Management[4] compiles statistics[5] on crises across the globe every year. It rates 46% of these as “smoldering” in nature – that is, likely to have occurred after red flags or warning signs.

Sometimes top decision-makers are aware of the problem but don’t see it as a priority.

This appeared to be the case at the Pike River coal mine in New Zealand, where a gas explosion in 2010 caused a mine collapse, killing 29. The ensuing royal commission[14] found that in the previous seven weeks the financially stressed company had “failed to heed numerous warnings of a potential catastrophe at the mine”.

The commission concluded:

In the drive towards coal production the directors and executive managers paid insufficient attention to health and safety and exposed the company’s workers to unacceptable risks. Mining should have stopped until the risks could be properly managed.

And sometimes warning alarms are literally turned off.

Following the disastrous explosion and fire on the ill-fated Deepwater Horizon oil rig in the Gulf of Mexico, killing 11 workers, in 2010, a US government investigation was told vital safety warning systems had been deliberately disabled[15] to spare workers being awoken by false alarms.

Experts will try to resolve exactly how and why the Titan joined the Titanic on the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean – and whether the disaster could have been avoided if the many prior safety concerns had not been “explained away”.

The best crisis management is to prevent the crisis in the first place. Whether it is companies or governments or communities or individuals, when there are warning signs of impending disaster speak up, and keep speaking up, until someone takes action.

Read more: 3 crisis-leadership lessons from Abraham Lincoln[16]

References

- ^ wrote in 2018 (thenewdaily.com.au)

- ^ least one employee (www.bbc.com)

- ^ had to sign (www.bbc.com)

- ^ Institute for Crisis Management (crisisconsultant.com)

- ^ compiles statistics (crisisconsultant.com)

- ^ ICM annual crisis report 2021 (crisisconsultant.com)

- ^ CC BY (creativecommons.org)

- ^ says (assets.ctfassets.net)

- ^ Ian Mitroff (mitroff.net)

- ^ agree (assets.ctfassets.net)

- ^ Why PR agencies and their spin should be the subject of greater scrutiny (theconversation.com)

- ^ the bank failed (www.nytimes.com)

- ^ clear warnings (www.theage.com.au)

- ^ royal commission (pikeriver.royalcommission.govt.nz)

- ^ deliberately disabled (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ 3 crisis-leadership lessons from Abraham Lincoln (theconversation.com)

Authors: Tony Jaques, Senior Research Associate, RMIT University