rapid global warming 55 million years ago shows us what the future may hold

- Written by Milo Barham, Senior Lecturer, Curtin University

Frozen northeast Greenland seems an unlikely place to gain insight into our ever-warming world. Between 50 million and 60 million years ago, however, the region was a different place.

Back then Greenland had a subtropical climate befitting of its name. It was host to volcanic activity that restructured the land and ocean connections and drove rapid warming.

The abrupt global warming event 56 million years ago, known as the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM), is often used as a worrying analogue for our current climate crisis.

Our research, published today in Communications Earth and Environment[1], provides crucial details about the event — with a focus on Greenland’s role in it.

Read more: Volcanic emissions caused the warmest period in past 56m years – new study[2]

Lessons from Earth’s past

About 56 million years ago, increased volcanic activity resulted in the eruption of huge volumes of molten rock, in a vast area surrounding what would eventually become Iceland. Underground, the magma essentially “cooked” sediments rich in organic material, converting the stored carbon into gas.

This led to trillions of tonnes of greenhouse gases being released into the atmosphere. It drove an increase in ocean acidity and a rise in global temperatures to the tune of 5-8℃.

The environmental and ecological consequences were immense. Mass extinctions and animal migrations took place over just a few thousand years. Fast-forward to the release of the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change[3] report, and there has never been a greater need to understand Earth’s climate systems.

The geological record provides an opportunity to learn from past climate events that occurred on a timescale far longer than human lifespans or any written history.

Most importantly, it could forewarn us of the outcomes of Earth’s current climate upheaval which is unfolding much more rapidly.

Greenland’s exotic land

Northeast Greenland is the world’s largest national park, and one of the most remote and unexplored areas on the planet.

For our study, we set out to map the environmental evolution and geographic response to volcanic activity throughout the PETM event in northeast Greenland. Volcanic activity has been identified as the “smoking gun” for what drove the PETM warming.

Greenland also acted as a gatekeeper for the once-narrow seaway that connected the Arctic and Atlantic oceans (before movement of the tectonic plates opened the Atlantic more fully).

Greenland therefore played a significant role in regulating climate-critical ocean connections. These channels control the distribution of heat, dissolved gasses such as oxygen and carbon dioxide, nutrients and moisture in the atmosphere.

Midnight sunset in the pristine northeast Greenland wilderness.

Milo Barham

Midnight sunset in the pristine northeast Greenland wilderness.

Milo Barham

Our international team of geologists carefully mapped sediments and lava flows onshore in northeast Greenland, and in rock cores extracted from the nearby sea bed.

We identified and dated various microscopic plant and plankton fossils, which provided detailed information about the environment they would have lived in. This was combined with findings gleaned from tracing the echoes of sound waves under the seabed.

By measuring how sound waves are reflected by buried sediment, we mapped the thickness and development of the geological layers. This revealed how the landscape, now partly covered by ocean, evolved over time.

With this, we carefully resurrected an image of northeast Greenland as it was between 47 and 63 million years ago.

A hotter, wetter planet

We discovered that around the time of the PETM, volcanic uplift turned deeper marine environments around northeast Greenland into shallow estuaries, rivers and vegetated swampy floodplains.

Some carbonised fossil leaf impressions in finely laminated sediment, retrieved from the Wollaston Forland peninsula in northeast Greenland.

Jussi Hovikoski

Some carbonised fossil leaf impressions in finely laminated sediment, retrieved from the Wollaston Forland peninsula in northeast Greenland.

Jussi Hovikoski

Around 56 million years ago lava began erupting across the region, building volcanic rock piles hundreds of metres high. As successive lava flows emerged, the hot, wet climate of the time eventually caused the surface to break down into a red soil called laterite.

Dr Steven Andrews inspecting the boundary between successive lava flows in Wollaston Forland in northeast Greenland. The faint red band directly above the geologists head represents the eruption surface of a lava flow that was broken down into laterite by the hot wet climate.

Milo Barham

Dr Steven Andrews inspecting the boundary between successive lava flows in Wollaston Forland in northeast Greenland. The faint red band directly above the geologists head represents the eruption surface of a lava flow that was broken down into laterite by the hot wet climate.

Milo Barham

Our data from northeast Greenland are consistent with broader Arctic greenhouse reconstructions of the time. Both paint a picture of lush, swampy woodlands inhabited by cold-blooded reptiles, primates and hippo-like beasts unlike anything you’d see in today’s cooler world.

Ocean gateways and land bridges

Our work also reconstructs seabed uplift, and the emergence of large areas of land from the ocean. This is important as it would have caused a severe obstruction of the seaway that separated Greenland and Norway.

Such blockages are bad news. We know from the geological record that if critical ocean circulation stops, it can lead to dangerously acidic[4] and oxygen-starved oceans[5], as well as enhanced climate disturbance.

That said, when the flow of water between the Atlantic and Arctic was constricted because of emerging land during the PETM, there was more opportunity for plants and animals to move around. The continental connection allowed species to migrate into cooler climates and escape the effects of the warming.

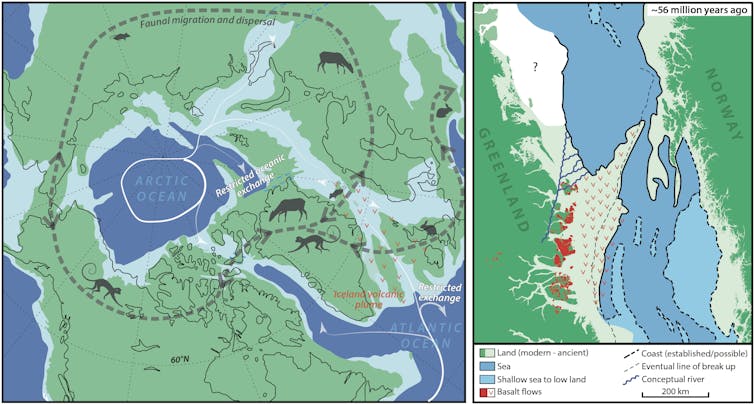

This schematic diagram of the Arctic 50 to 60 million years ago shows how volcanic uplift would have narrowed the seaway between Greenland and Norway, restricting ocean exchange and consequently boosting flora and fauna migration.

modified from Ron Blakey (2021) - https://doi.org/10.4138/atlgeol.2021.002 and Jussi Hovikoski et al. (2021) - https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-021-00249-w

This schematic diagram of the Arctic 50 to 60 million years ago shows how volcanic uplift would have narrowed the seaway between Greenland and Norway, restricting ocean exchange and consequently boosting flora and fauna migration.

modified from Ron Blakey (2021) - https://doi.org/10.4138/atlgeol.2021.002 and Jussi Hovikoski et al. (2021) - https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-021-00249-w

Back to the future

Today’s environments have been largely broken up by human activity through agriculture and urbanisation, which gives species under environmental stress less opportunity to move elsewhere to survive any change.

And although we’re still some way from matching the overall volume of greenhouse gas emissions released during the PETM, today’s emission rates are rising almost ten times faster[6]. Our ecosystems are already displaying signs of destabilisation.

Recent studies[7] have warned of weakening ocean circulation, which may lead to climatic tipping points. Without urgent intervention, the unfolding climate and ecological crisis could prove to be a far greater burden than the world can bear.

Read more: Satellites reveal ocean currents are getting stronger, with potentially significant implications for climate change[8]

References

- ^ Communications Earth and Environment (doi.org)

- ^ Volcanic emissions caused the warmest period in past 56m years – new study (theconversation.com)

- ^ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (www.ipcc.ch)

- ^ dangerously acidic (eos.org)

- ^ oxygen-starved oceans (theconversation.com)

- ^ almost ten times faster (www.sciencedaily.com)

- ^ Recent studies (theconversation.com)

- ^ Satellites reveal ocean currents are getting stronger, with potentially significant implications for climate change (theconversation.com)