Fossil tooth fractures and microscopic detail of enamel offer new clues about human diet and evolution

- Written by Ian Towle, Postdoctoral fellow, University of Otago

Teeth can tell us a lot about the evolution of prehistoric humans, and our latest study[1] of one of our species’ close relatives may finally resolve a long-standing mystery.

The genus Paranthropus is closely related to ours, Homo, and lived about one to three million years ago. Both Paranthropus and Homo are often considered to have evolved from Australopithecus, represented by the famous fossils Lucy[2] and Mrs Ples[3].

The Paranthropus group stands out in our family tree because of their massive back teeth, several times the size of ours, and their extremely thick enamel (the outer-most layer of our teeth). This prompted the hypothesis that they ate mostly hard foods, and one of the most complete Paranthropus specimens was dubbed the Nutcracker Man.

The jaw of Paranthropus robustus shows large molars.

Author provided (no reuse)

The jaw of Paranthropus robustus shows large molars.

Author provided (no reuse)

But our study shows Paranthropus had very low rates of enamel chipping (a common type of tooth fracture), comparable to living primates such as gorillas and chimpanzees, which rarely eat hard foods. This supports other recent research[4] about the diet of this group and should finally put to rest the nutcracker hypothesis.

Reconstructing diet from teeth

Our understanding of diet and behaviour during human evolution has changed markedly over the last decades — partly due to new technologies but also because of some spectacular fossil discoveries.

Teeth are often at the forefront of this research. They are by far the most abundant resource because they survive fossilisation better than bones. This is a fortunate circumstance because teeth also offer other information that helps us to reconstruct the environment of our fossil ancestors and relatives.

We can glean a lot of information from the microscopic scratches created by foods scraping along the tooth surface during chewing, the tiny particles preserved in dental plaque and the chemical composition of the teeth themselves.

Read more: Discovered: the earliest known common genetic condition in human evolution[5]

Before such techniques were developed and refined, researchers relied on looking at the overall shape and size of teeth, as well as wear and chipping visible with the naked eye. Small sample sizes and a lack of comparative material hampered these studies, but they provided some bold claims about the diet of our fossil ancestors.

For most techniques, we need large data sets from both extinct and living species for comparison. For example, a species that commonly eats lots of hard seeds and nuts should theoretically show high rates of tooth chipping. But without a large database of species, we wouldn’t know if 10% of teeth displaying fractures is normal for a hard object feeder, or simply an expected percentage caused by other factors.

Tooth chipping

In our recent research[6], we have studied a broad range of living primates and compared that information with data on fossil species. The results were surprising, with our species Homo sapiens and fossil relatives in our genus commonly showing high rates of chipping, similar to living primates that eat hard foods habitually.

Earlier studies regularly suggested humans evolved smaller teeth in the last couple of million years in response to cooking and processing foods and eating more meat, while Paranthropus evolved large robust teeth in repose to eating lots of hard foods.

This baboon tooth, an upper molar, has been chipped on the outside.

Author provided

This baboon tooth, an upper molar, has been chipped on the outside.

Author provided

But teeth can evolve in more ways than simply the overall size or the thickness of the enamel. The microscopic structure and composition of dental tissue can also vary among species. Could such variation explain chipping and wear differences among species?

If so, this could explain why small-toothed humans have lots of chipping on their teeth while the big-toothed Paranthropus has barely any.

Mechanical and structural properties of teeth

To address these questions, we sectioned teeth[7] of several living primate species, including humans, to look at variation in mechanical and structural properties across tooth crowns. We collected non-human primate teeth from museums. Human teeth were donated by patients during routine dental treatments.

The mechanical testing involved a tiny diamond-tipped probe, which produced readings of the hardness and elasticity of enamel. We used high-powered microscopes and micro-CT scans to analyse the structure and mineral density of enamel.

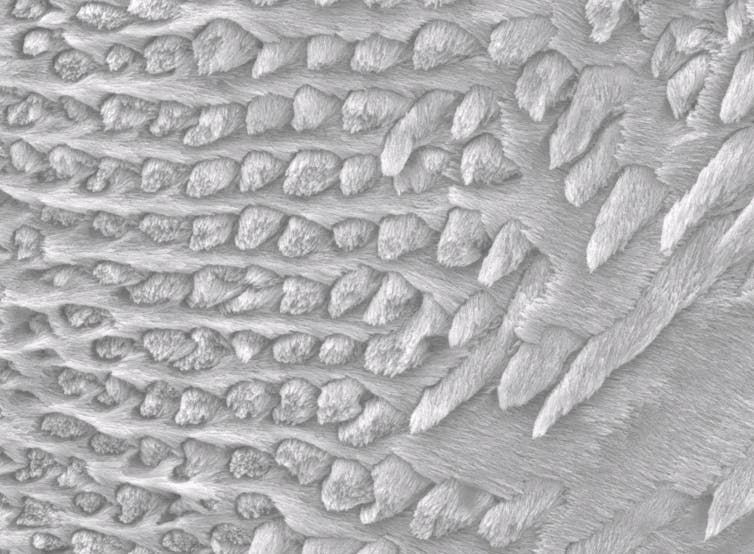

Detail of the microscopic structure of a baboon’s molar enamel.

Author provided

Detail of the microscopic structure of a baboon’s molar enamel.

Author provided

The results show mechanical and structural properties are uniform among primate groups. The surfaces most prone to fracture[8] in primates – the inner side of lower, and outer side of upper back teeth – have significantly harder enamel.

These patterns are similar regardless of the diet of the primates. This suggests the inner structure of enamel plays a crucial role in protecting the tooth, but these patterns have remained remarkably stable during primate evolution.

We argue that other tooth properties, including the overall size and shape of teeth, evolve quicker to cope with changes in diet. Therefore, the evidence from chipping patterns and tooth structure of living primates suggest Paranthropus rarely ate hard foods and their enormous back teeth likely evolved for other purposes, likely to chew large quantities of very tough leafy material.

Read more: Human ancestors had the same dental problems as us – even without fizzy drinks and sweets[9]

Why fossil humans have such high rates of chipping requires further research, but we propose several explanations, including accidental ingestion of grit and using front teeth as a “third hand” to hold non-food items. For example, large fractures on the front teeth of Neanderthals[10] may be due to this tool-use behaviour, and small chips on the back teeth of Homo naledi[11] likely relate to chewing grit-laden foods.

But it goes against the neat idea that we evolved smaller teeth when we started using fire and processing more high-quality foods, since heavy wear and fractures remained. The notion of nutcracker and cooking/meat-eating groups was appealing in its simplicity. Based on the changing shape and size of teeth through time, it seemed a reasonable hypothesis. But the actual wear and tear of fossil teeth tells a very different story that is slowly coming to light.

References

- ^ latest study (doi.org)

- ^ Lucy (www.nature.com)

- ^ Mrs Ples (theconversation.com)

- ^ other recent research (journals.plos.org)

- ^ Discovered: the earliest known common genetic condition in human evolution (theconversation.com)

- ^ recent research (doi.org)

- ^ we sectioned teeth (doi.org)

- ^ most prone to fracture (doi.org)

- ^ Human ancestors had the same dental problems as us – even without fizzy drinks and sweets (theconversation.com)

- ^ front teeth of Neanderthals (doi.org)

- ^ back teeth of Homo naledi (doi.org)