'What country have you walked?' Why all Australians should walk an Indigenous heritage trail

- Written by Stephen Muecke, Professor of Writing, Flinders University

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised this article contains images and names of deceased people.

The Goolarabooloo community in Broome has been running the Lurujarri Heritage Trail[1] for over 30 years. In July each year, tourists are welcomed by the Roe family, and embark on an eight-day trek.

Swags and tents are piled on the truck, so the walkers only have to carry a day pack. They soon pass the famous Cable Beach where less adventurous tourists are basking in the sun, and continue their walk along the beach admiring the contrast of aquamarine ocean and red pindan cliffs.

On trail, the colonial power dynamic between settler and Indigenous communities is turned on its head. The Goolarabooloo express their sovereignty (never ceded) by welcoming visitors onto their Country.

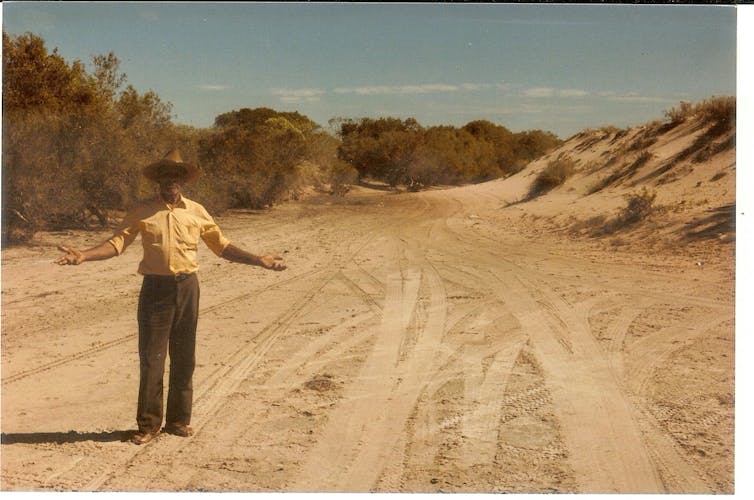

Paddy Roe at Minariny.

Author, Author provided

Paddy Roe at Minariny.

Author, Author provided

This kind of tourism is a rare, life-changing experience. What is special about the Lurujarri Trail is the participation of the Roe family. “Over eight days, we become friends,” tour leader Daniel Roe tells the group.

Trailblazing

It was Daniel’s late great-grandfather, Paddy Roe[2], who had the idea for the trail in 1987. I had written a couple of books with him, and we were working on a third at the time, which I have only just delivered on: The Children’s Country[3].

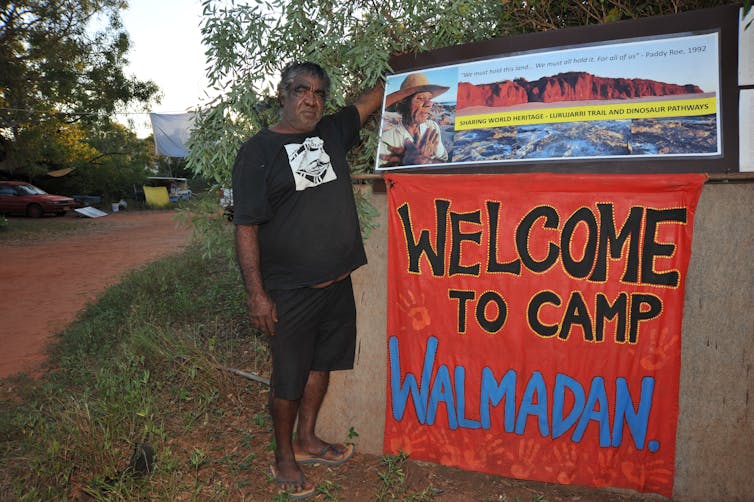

He wanted the text to document and protect Country from developers and miners. But it turned out the trail was a better idea. When Woodside Energy and the Western Australian government wanted to build a huge gas hub in the middle of the trail, at Walmadany, James Price Point, over ten years ago, it was the Goolarabooloo that stood in the way, and eventually won the battle[4].

Goolarabooloo elder Philip Roe stands next a photo of his grandfather, the late Paddy Roe, at the Walmadan camp near James Price Point.

AAP Image/Cortlan Bennett[5]

Goolarabooloo elder Philip Roe stands next a photo of his grandfather, the late Paddy Roe, at the Walmadan camp near James Price Point.

AAP Image/Cortlan Bennett[5]

Hundreds of people had walked the trail over the years and some came back to help in the campaign. They had developed a kind of gut feeling for Country the Goolarabooloo call liyan.

Read more: Without James Price Point, what now for Browse Basin gas?[6]

Extractive industries

White Europeans only arrived in West Kimberley at the end of the 19th century, so elders like Paddy Roe[7], who lived from about 1912 to 2001, saw their arrival unfold.

In recent years, stark divisions over mining money have emerged in the Aboriginal community and Native Title determinations have exacerbated the divisions. The Goolarabooloo did not get any Native Title rights, as their neighbours did. Some speculate their opposition to the gas had a lot to do with it[8].

In a sense, the walking trail is land rights by other means. They are maintaining their knowledge and passing it on.

Dreaming stories (called bugarrigarra, the law) connect communities and follow old trade routes, down through the Western Desert via Uluru into southern parts, where the local pearl-shell used to be be traded for ochre, native tobacco or new song cycles.

Gantheaume Point. Indian Ocean view of the rocky red cliffs along the Lurujarri Heritage Trail, with Cable Beach in the distance.

Shutterstock[9]

Gantheaume Point. Indian Ocean view of the rocky red cliffs along the Lurujarri Heritage Trail, with Cable Beach in the distance.

Shutterstock[9]

Read more: Songlines: Tracking the Seven Sisters is a must-visit exhibition for all Australians[10]

There are dozens of Aboriginal walking tracks across Australia: well-known are the Larapinta in Central Australia, the Bundian Way between Targangal (Kosciuszko) and Bilgalera on the coast near Eden, and Mungo Aboriginal Discovery Tours.

But it is hard to find another with the Lurujarri Heritage Trail’s family involvement, ocean swimming, bush tucker, and the most extensive set of dinosaur footprints[11] in Australia.

Read more: Friday essay: how our new archaeological research investigates Dark Emu's idea of Aboriginal 'agriculture' and villages[12]

More Indigenous-led walking tracks could trace storied landmarks.

In Kaurna Country around Adelaide, there is the story of Tjilbruke[13]. This ancestor was a law man whose nephew Kulultuwi was hunting emu that were forbidden to him.

Tjilbruke was prepared to overlook the transgression, but Kulultuwi’s half-brothers speared him. Tjilbruke, in mourning, carried the body of his nephew down the coast, stopping to weep at various points where there are now freshwater springs.

Read more: Friday essay: this grandmother tree connects me to Country. I cried when I saw her burned[14]

Walking schools

There is increasing awareness of how Indigenous knowledges are relevant to caring for Country[15].

“Things must go both ways,” Paddy Roe used to say to me.

He had already experienced practices that saw knowledge transfer going one way. People would ask him about his Country in order to exploit it, for water, for pasture, for pearl-shells and now for gas and oil.

Walking tracks can teach what each territory is capable of sustaining. The people further down the track know their Country is that little bit different and what it is capable of. These pathways connect up, and knowledge transforms along the way.

People often ask, “What school did you go to?” Perhaps one day, in Australia, they will ask, “what Country have you walked?”

References

- ^ Lurujarri Heritage Trail (www.goolarabooloo.org.au)

- ^ Paddy Roe (www.goolarabooloo.org.au)

- ^ The Children’s Country (www.booktopia.com.au)

- ^ eventually won the battle (theconversation.com)

- ^ AAP Image/Cortlan Bennett (photos-cdn.aap.com.au)

- ^ Without James Price Point, what now for Browse Basin gas? (theconversation.com)

- ^ Paddy Roe (meanjin.com.au)

- ^ had a lot to do with it (nit.com.au)

- ^ Shutterstock (image.shutterstock.com)

- ^ Songlines: Tracking the Seven Sisters is a must-visit exhibition for all Australians (theconversation.com)

- ^ dinosaur footprints (www.australiangeographic.com.au)

- ^ Friday essay: how our new archaeological research investigates Dark Emu's idea of Aboriginal 'agriculture' and villages (theconversation.com)

- ^ Tjilbruke (kaurnaculture.wordpress.com)

- ^ Friday essay: this grandmother tree connects me to Country. I cried when I saw her burned (theconversation.com)

- ^ caring for Country (theconversation.com)