70% of Indigenous people in Sydney live in neighbourhoods with low walkability

- Written by Meead Saberi, Senior lecturer, UNSW

Indigenous inequality in Australia[1] has long been known to the public and policy makers. Yet, successive local, state, and federal governments have failed to effectively make a noticeable change in Indigenous health and wellbeing.

These inequalities[2] include shorter life expectancy, poorer general health and lower levels of education and employment. Less known is transport inequality and its health implications for Indigenous people.

Walking is a healthy form of physical activity and is proven to reduce rates of chronic disease[3].

Neighbourhood walkability is associated with the number of trips people can make on foot. People living in areas with lower walkability tend to walk less.

Our research shows that 70% of the Indigenous population in the City of Sydney live in neighbourhoods with lower-than-average walkability. This has the potential to aggravate Indigenous people’s health issues, potentially widening the health gap with non-Indigenous Australians, instead of closing it.

Read more: Yes, we need to Close the Gap on health. But many patients won't tell hospitals they're Indigenous for fear of poorer care[4]

Closing the walkability gap

“Closing the Gap[5]” refers to the formal government commitment to close the significant health and life expectancy gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians by 2030.

Whether closing the gap targets will be successful or not remains a question[6]. For example, the rate of disability resulting from chronic diseases among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people has only slightly improved over the past ten years[7].

The NSW Closing The Gap implementation plan[8] includes 17 socioeconomic targets that aim to address inequalities in health, education and employment.

There is no action item in it focusing specifically on the role of active transport. The closest one is related to initiatives to reduce the prevalence of obesity for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults and children.

The role transport can play in enhancing walkability in neighbourhoods and improving people’s health outcomes[9] has been entirely overlooked.

Read more: 'Although we didn’t produce these problems, we suffer them': 3 ways you can help in NAIDOC's call to Heal Country[10]

Walking inequality in the City of Sydney

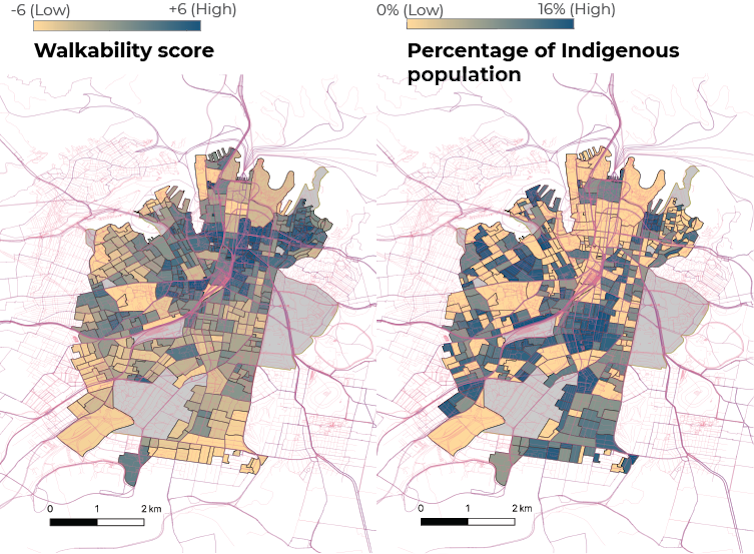

Our analysis of population and land use data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics for the City of Sydney shows there is a significant walkability inequality across the local government area.

We measured walkability using the Australian Urban Research Infrastructure Network (AURIN)[11] statistical tool. It considers three elements: street network connectivity, land use mix and population density.

Areas with the highest walkability scores: Potts Point, Darlinghurst, Surry Hills, Haymarket, Pyrmont, and Darlington

Areas with the lowest walkability scores: Rosebery, Beaconsfield, Redfern, Waterloo, Eveleigh and Alexandria

Our research shows that 70% of Indigenous people in the City of Sydney — nearly 2,500 people — live in neighbourhoods with a walkability score lower than the local government area average.

The absence of mixed residential and commercial land use, a disconnected street network and low population density make a neighbourhood less walkable.

The walking disadvantage of Indigenous population of City of Sydney.

Author provided

The walking disadvantage of Indigenous population of City of Sydney.

Author provided

How to make our neighbourhoods more walkable

The way to increase physical activity is through urban policies and planning practices that facilitate activity-friendly communities and encourage more walking.

A US study in 2017[12] has found that 43% of people who live in walkable neighbourhoods achieve physical activity targets. Conversely, only 27% of people who live in less walkable neighbourhoods achieve those targets.

Policies[13] that state and local governments can consider to address walking inequality include investing in pedestrian infrastructure and enhanced road safety and providing easy walking access to public transport.

Improving the first mile/last mile connections, encouraging mixed residential and commercial land use, and providing shops, parks and other public spaces within walking distance from people’s homes are other solutions.

Improving walking safety after dark for children and women, and reducing the distance to schools and workplaces are also shown to be effective.

This year, Sydney celebrated NAIDOC[14] week in lockdown. Yvonne Weldon, the elected chairperson of the Metropolitan Local Aboriginal Land Council and the first Aboriginal candidate for the lord mayor of Sydney[15], said[16],

We must commit to making our world, our society inclusive – breaking through barriers and not creating them.

There are great health and social benefits in having a more walkable place to live. They are even more significant for communities that have been traditionally disadvantaged. Reducing transport inequality and improving walkability in Indigenous communities are necessary to help close the health and social gap.

References

- ^ Indigenous inequality in Australia (www.jstor.org)

- ^ These inequalities (australianstogether.org.au)

- ^ reduce rates of chronic disease (doi.org)

- ^ Yes, we need to Close the Gap on health. But many patients won't tell hospitals they're Indigenous for fear of poorer care (theconversation.com)

- ^ Closing the Gap (www.closingthegap.gov.au)

- ^ remains a question (humanrights.gov.au)

- ^ only slightly improved over the past ten years (www.pc.gov.au)

- ^ NSW Closing The Gap implementation plan (www.aboriginalaffairs.nsw.gov.au)

- ^ people’s health outcomes (ijbnpa.biomedcentral.com)

- ^ 'Although we didn’t produce these problems, we suffer them': 3 ways you can help in NAIDOC's call to Heal Country (theconversation.com)

- ^ Australian Urban Research Infrastructure Network (AURIN) (aurin.org.au)

- ^ US study in 2017 (physicalactivityplan.org)

- ^ Policies (link.springer.com)

- ^ NAIDOC (www.naidoc.org.au)

- ^ candidate for the lord mayor of Sydney (yvonneweldon.com.au)

- ^ said (tedxsydney.com)