Technically accomplished, sonically subversive and fiercely independent, I’ll remember Steve Albini for his rare humility

- Written by Samantha Bennett, Professor of Music, Australian National University

The future belongs to the analogue loyalists. Fuck digital.

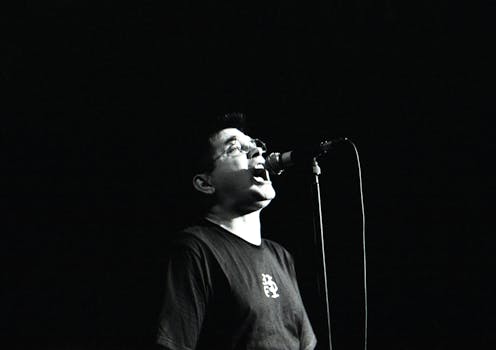

As a tsunami of CDs, DAT tapes and samplers swept the recording industry in the late 1980s, Big Black frontman and alternative music agent provocateur Steve Albini threw down the gauntlet in defiance.

His commitment to analogue recording processes and the permanency of analogue media resonated among alternative music communities sceptical of the major record industry, and their perceptions of impending digital doom.

This quote, taken from the liner notes of Big Black’s sophomore album Songs About Fucking (1987), signified the end of Albini’s band and the beginning of his recording career.

Albini’s untimely death at the age of 61 is a huge loss to independent music.

An analogue sound

A protégé of London’s Southern Studios recordist John Loder[1] (CRASS, Ministry, Jesus and Mary Chain), Albini peeled the remnants of analogue recording from Southern’s sticky floors and stuck it all over Chicago’s alternative music scene.

He quickly carved out a reputation as a go-to recordist for artists wanting to achieve a transparent representation of a live sonic aesthetic.

From The Jesus Lizard to Manic Street Preachers, Pixies to The Stooges, Albini applied his same raw-and-roomy drum microphone techniques alongside uncompromisingly upfront guitars to every session – regardless of whether the client was an indie rock giant or an emergent local band.

In 2003, Albini’s commitment to technologically unobtrusive recording sessions was immortalised in David Josephson’s e-22S[2] – a small diaphragm condenser microphone built to Albini’s requirements and bearing his Electrical Audio studio insignia.

The power of words – and music

As a journalism graduate from Northwestern University, Albini routinely provoked outrage with his nonchalant commentary of extreme events and material, writing for local fanzines and reviewing the Chicago punk scene.

Armed with a Roland TR606 drum machine and a penchant for horror stories in the local news, I previously described[3] Albini’s noise-punk as “designed to confront listeners with real-life horrors of suburbia, to reflect bigotry and social exclusion and to mediate the extremities of human behaviour via equally confronting music.”

In 2020, Albini apologised[4] for his confrontational writing – and later band name Rapeman – as “unconscionable” and “indefensible”, a result, he said, of his unchecked privilege.

All apologies aside, it is hardly likely the dozens of women and LGBTQI+ artists Albini recorded – including Laura Jane Grace, The Breeders, Nina Nastasia, Screaming Females and PJ Harvey, to name but a few – would have set foot in his studio had Albini’s deviant satirising reflected his true politics or beliefs.

After all this is the man, who when writing[5] to Nirvana to pitch the recording for their In Utero album, told them he’d “rap your head with a ratchet” in the same letter he humbly insisted on no points or royalties.

The only person I wanted to call

Albini’s reputation as an unapproachable and prickly recalcitrant was far from the truth.

For those fortunate enough to have recorded with Albini, he was known as a kind, patient and accommodating engineer, eager to make bands feel at home and committed to capturing the truest possible representation of their live sound.

This was my experience, too.

As a young doctoral student researching sound recording and production techniques in 2009, Albini was only too happy to discuss his career and recording techniques with me.

“I feel like it borders on the fraudulent for me to charge for a recording session knowing that the product of that recording session is going to be impermanent,” he told me. He was adamant tape was still the only reliable recording medium well into the 21st century.

A couple of years later when we needed a keynote for the Art of Record Production conference, there was only one person I knew to call. Albini happily obliged – despite spending most of the conference weekend glued to online poker tournaments.

As an analogue loyalist, Albini was perhaps the recording industry’s last man standing. Technically accomplished, sonically subversive and fiercely independent, in his later years he showed a rare humility for a decorated recording engineer, and an open willingness to teach in the face of relentless industry gatekeeping.

Never a nostalgic, Albini demythologised recording processes with a stream of recording videos shot from his own Electric Audio studios. Dressed in his trademark navy blue overalls and beanie, just a week ago Albini happily explained the schematic of a SamAmp VA tube preamplifier in a video[6] that effortlessly blends in-depth electronics theory with an exuberant punk joy de vivre.

Albini’s final album with band Shellac, To All Trains, will be released on May 17.

References

- ^ John Loder (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ David Josephson’s e-22S (www.audiotechnology.com)

- ^ I previously described (onlinelibrary.wiley.com)

- ^ apologised (www.youtube.com)

- ^ when writing (news.lettersofnote.com)

- ^ in a video (www.youtube.com)