Despite what you might hear, weather prediction is getting better, not worse

- Written by Andrew King, Senior Lecturer in Climate Science, The University of Melbourne

Australia’s weather bureau copped harsh criticism[1] after El Niño failed to deliver a much-vaunted dry summer in eastern Australia. Parts of northern Queensland in the path of Tropical Cyclone Jasper had a record wet December and areas of central Victoria had a record wet January. Overall, the summer was 19% wetter than average for Australia as a whole[2].

This led to debate[3] in the media and during senate estimates around the Bureau of Meteorology’s ability to make accurate predictions as the climate changes. The value of seasonal forecasting in particular has been called into question.

Weather prediction has actually improved in recent years. And there are exciting developments on the horizon[4] involving artificial intelligence. But the effect of future climate change on weather and seasonal prediction is not yet well understood.

As climate scientists, we know 7–14-day forecasts and seasonal predictions stack up pretty well when it comes to the crunch. That’s because agencies such as the Bureau check the success of their forecasts against reality[5] and make this information public. While it’s possible climate change may pose challenges to weather and seasonal prediction in some regions, we believe improvements in forecasting far exceed any losses in accuracy.

Read more: Did the BOM get it wrong on the hot, dry summer? No – predicting chaotic systems is probability, not certainty[6]

Advances in prediction

Ever since the UK physicist Lewis Fry Richardson[7] first envisaged the possibility in a 1922 book[8], weather forecasting has been growing more accurate and powerful.

The science of meteorology took a great leap forward with the boom in computing capability.

Now, highly detailed satellite data and weather observations feed into multiple computer simulations. This makes 7-day forecasts pretty accurate[9] across the globe, although less so in poorer areas of the world.

As we can never know the state of the atmosphere perfectly at any given time, it is beneficial to run many simulations[10] with slightly different starting conditions. This gives an idea of how the weather may change and how much confidence we have in those changes.

The same principles that govern weather forecasting also support seasonal climate forecasting. Models representing the atmosphere and ocean are cast forward in time to give a three-month outlook.

Beyond about ten days we’re not able to say with certainty what the weather will be like for a precise location at a specific time. But we can give an indication of the chances the weather will be significantly hotter, cooler, drier or wetter than the seasonal average.

Our ability to predict conditions over the coming season has greatly advanced in just the past 20 years. We now better understand how the various climate drivers influence our weather, and we have more computational power to run models.

However model-based seasonal forecasting – providing location-specific guidance on likely rainfall and temperature compared to the long-term average for months at a time – is still relatively new. It has further to go to provide reliable, usable information to decision-makers.

How do we measure how good a forecast is?

Meteorologists know whether their forecasts were right or wrong after the fact, because agencies such as the Bureau of Meteorology have entire teams dedicated to comparing their forecasts with what actually happened[11].

The table above shows a simple example of how scientists calculate how good a forecast is. From the number of hits, misses, false alarms and correct negatives we can calculate a range of scores.

This becomes more complex when we want to know not just whether the forecast correctly predicted it would rain, but also how much rain, and whether the quoted probability of rainfall was actually right.

Read more: Did the BOM get it wrong on the hot, dry summer? No – predicting chaotic systems is probability, not certainty[12]

Additionally, as models become more sophisticated and higher-resolution than they used to be, they can simulate more realistic-looking weather systems such as lines of thunderstorms. It’s like watching TV in high definition instead of grainy black and white. Assessing forecast capability gets more challenging at high resolutions because flaws we wouldn’t previously have seen are magnified too.

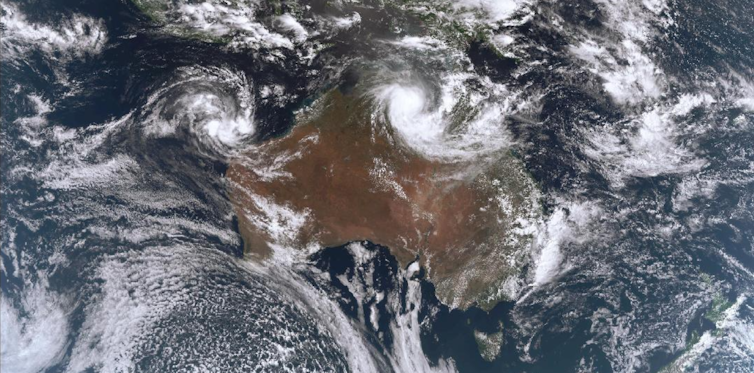

Overall, when we look at weather forecast skill over time, we see major improvements[13]. These improvements are particularly large in the Southern Hemisphere, where there is less land for weather stations. In these remote areas, satellite data has vastly improved our knowledge of the state of the atmosphere – providing a better starting point for forecast simulations.

Seasonal forecasting capability is also improving, but there is less study of these changes. Skill of seasonal outlooks varies depending on the time of year and on whether major climate influences such as the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (the year-to-year swing between El Niño, neutral and La Niña phases) are active.

Seasonal forecasts are the best in spring when the El Niño-Southern Oscillation is at its peak and El Niño or La Niña is often providing a strong and predictable push to seasonal rainfall and temperatures. In contrast, seasonal forecasts are typically worse in autumn when the El Niño-Southern Oscillation transitions between phases and the drivers of wet or dry conditions are less predictable.

Read more: What does El Niño do to the weather in your state?[14]

So is climate change affecting our ability to predict the weather?

Climate change is certainly changing our weather. But it’s not clear if that’s making weather harder to predict. There hasn’t been much research into this yet.

Some changes could affect predictability, particularly if more rain falls from isolated thunderstorms and less from larger-scale weather systems. This is the general expectation with climate change[15] and already appears to be happening in parts of Australia[16]. Such a change is not well understood but would likely make local rainfall totals harder to predict.

We already see lower seasonal prediction skill in summer when more rain falls in small-scale systems not strongly tied to the El Niño-Southern Oscillation[17]. Changes in the strength of the relationship between climate influences, such as the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, and Australian climate could also make seasonal prediction easier or harder.

Given the rate of improvement in weather prediction has been so high, it’s unlikely anyone would notice any effect of climate change on weather forecast skill any time soon. As weather forecasting and seasonal prediction continue to improve due to scientific and technological advances this will likely drown out any climate change effect on prediction.

Read more: Here's why climate change isn't always to blame for extreme rainfall[18]

References

- ^ weather bureau copped harsh criticism (www.afr.com)

- ^ 19% wetter than average for Australia as a whole (www.bom.gov.au)

- ^ led to debate (www.smh.com.au)

- ^ on the horizon (www.scientificamerican.com)

- ^ against reality (www.bom.gov.au)

- ^ Did the BOM get it wrong on the hot, dry summer? No – predicting chaotic systems is probability, not certainty (theconversation.com)

- ^ Lewis Fry Richardson (cosmosmagazine.com)

- ^ in a 1922 book (www.britannica.com)

- ^ pretty accurate (ourworldindata.org)

- ^ many simulations (www.metoffice.gov.uk)

- ^ comparing their forecasts with what actually happened (www.cawcr.gov.au)

- ^ Did the BOM get it wrong on the hot, dry summer? No – predicting chaotic systems is probability, not certainty (theconversation.com)

- ^ we see major improvements (www.nature.com)

- ^ What does El Niño do to the weather in your state? (theconversation.com)

- ^ with climate change (agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com)

- ^ in parts of Australia (theconversation.com)

- ^ not strongly tied to the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (link.springer.com)

- ^ Here's why climate change isn't always to blame for extreme rainfall (theconversation.com)