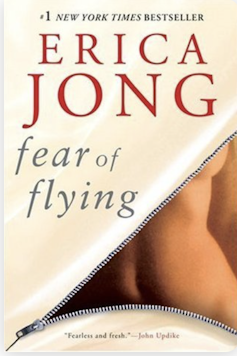

Erica Jong’s Fear of Flying has a joyful abandon rarely found in today’s sad girl novels

- Written by Kath Kenny, Sessional academic, Department of Media, Communications, Creative Arts, Language, and Literature, Macquarie University

In our feminist classics series, we look at influential books.

Fear of Flying[1], Erica Jong’s 1973 blockbuster novel, begins with an ingenious opening line.

There were 117 psychoanalysts on the Pan Am flight to Vienna and I’d been treated by at least six of them.

In those 21 words Jong introduces her book’s droll, wisecracking tone, suggesting a journey that will transport her narrator’s mind and body. The reference to a post-war Vienna foreshadows the book’s more serious themes. But another three words Jong coined, “the zipless fuck”, are most often credited for Fear of Flying’s reported 35 million plus sales[2] (and more on this later).

We soon learn the novel’s heroine, Isadora Wing, is accompanying Bennett, her Chinese-American psychiatrist husband, to an international congress in honour of Freud. A couple of years earlier, the newly married couple had lived on a US army base in Heidelberg, and Isadora is alert to the antisemitism still thriving in Europe. She imagines the reception awaiting them in Vienna, from the people “who invented schmaltz (and crematoria)”:

Welcome back! Welcome Back! At least those of you who survived Auschwitz, Belsen, the London Blitz, and the co-optation of America.

Isadora (as Jong was in the early 1970s) is a 29-year-old writer from an artistic New York Jewish family who has recently published a book of erotic poetry. She is also terrified of flying (understandable in the 1970s, an era when plane crashes and hijackings were not uncommon):

My fingers (and toes) turn to ice, my stomach leaps upwards into my ribcage, the temperature in the tip of my nose drops to the same level as the temperature of my fingers, my nipples stand up and salute the inside of my bra (or in this case, dress – since I’m not wearing a bra).

Isadora’s fear of flight seems to contradict her surname: marriage, she says, has given her a safe nest, the quietude she needs to create. But she can’t stop thinking about using her wings, about other lives she could lead. It’s no coincidence this story begins on a plane, a space suggesting new possibilities, charged with erotic potential as well as the distant prospect of being extinguished.

Read more: Andrea Dworkin's Intercourse: the raw, radical critique of male power resonating with Gen Z feminists today[3]

Id versus ego

In Vienna, where Isadora is writing about the conference for Voyeur magazine, she meets analyst Adrian Goodlove. A paunchy Englishman with dirty toenails, shaggy blond hair and a pipe “hanging out of his face”, he looks at her “the way a man smiles when he’s lying on top of you after a particularly good lay”. And he delivers the first of what will be many backhanded compliments: “If you’d stop being paranoid for a minute and use charm instead of main force, I’m sure nobody could resist you”.