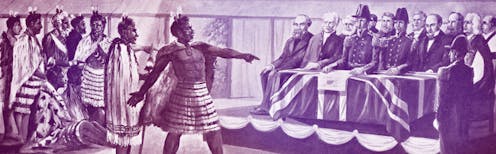

why the Treaty of Waitangi remains such a ‘bloody difficult subject’

- Written by Bain Munro Attwood, Professor of History, Monash University

The Treaty of Waitangi, the influential historian Ruth Ross (1920-1982) remarked in 1972, is “a bloody difficult subject”. She should have known – she devoted most of her working life to trying to make sense of it, especially the text in te reo Māori.

That difficulty persists to this day.

Discussion and debate in New Zealand about te Tiriti o Waitangi/the Treaty of Waitangi has been dominated for decades by two kinds of discourse: history (or rather what is thought to be history) and the law.

Much of what has been taken for history about te Tiriti/the Treaty has been produced by those who have worked outside the universities in Aotearoa New Zealand. History is a discipline that doesn’t present many strong barriers to those who wish to participate in the conversations and controversies it can stir up.

Anyone, whether academically trained or not, can presume to do history, discuss and debate it. This has increasingly become the case as the practice of history has been democratised in recent times.

It’s also the case, as I point out in my new book, ‘A Bloody Difficult Subject’: Ruth Ross, te Tiriti o Waitangi and the Making of History[1], that only some of the story about te Tiriti/the Treaty that has had the most impact on public life in New Zealand has been produced in accordance with the scholarly protocols of the discipline of history.

This is because it takes the form of foundational history. This is a kind of historical work in which authors claim that a particular event or text – in this case the making of the Treaty/te Tiriti or the texts of te Tiriti and the Treaty – comprises principles, whether moral or legal, that created the very foundations of the nation.