Why Lent is the perfect time to spiritually prepare for revolution

- Written by Kristie Patricia Flannery, Research Fellow, Institute for Humanities and Social Sciences, Australian Catholic University

It was around this time of year back in 1763 that Filipino rebels rode into Sinait[1] on horseback, shouting “in God’s mercy, the time has come to leave our slavery!”

The residents of this coastal village in Ilocos were among the tens of thousands of peasants across the big northern island of Luzon who joined the armed revolt[2] against Spanish colonial rule that year. The insurgency attracted men and women from diverse ethno-linguistic groups. They were Ilocanos, Pangasinanes, Cagayanes and Tagalogs. Theirs was the biggest rebellion to erupt in the Philippines in the 18th century. It was simultaneously a very radical and profoundly Catholic social movement.

The rebellion coincided with the Christian season of Lent: the 40 days of sombre prayer and self-discipline leading up to Holy Week and Easter, when Christians remember the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ. Did this sacred time of year make ordinary Filipinos more willing to challenge the empire?

The British invasion of Manila at the end of 1762 triggered the revolt. The walled city had been the seat of the Spanish government in the islands since 1571, until British forces attacked and drove the Spanish governor into exile in the countryside.

This humiliating defeat of the Spanish struck many Filipinos as a rare opportunity to demand a better colonial bargain, or even to try and permanently overthrow the Spanish empire which had intruded into their lives.

Mobs of protesters raided government and convent armouries and marched on government buildings, brandishing weapons and demanding urgent change. They wanted to abolish the tribute, the annual head tax that Indigenous Filipinos (whom the Spaniards called indios) and Chinese migrants were forced to pay to the Crown. They also wanted to get rid of the polo, the system of forced labour that funnelled native men into stints of gruelling work for the state, building forts and cutting down trees to build galleons.

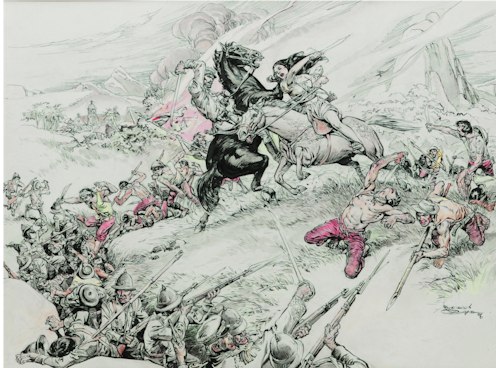

Colonial officials refused to negotiate, and the rebels decided to go to war to secure their demands. Battles broke out between rebel militias and those that remained loyal to Spain.

Lent inspired peasants to join the revolt against empire. The British invasion of the year before had destabilised the colonial government and prompted the armed rebellion. But it was Lent that inspired many peasants to join the rebel uprising.

Read more: Lent is here – remind me what it's all about? 5 essential reads[3]

A Catholic revolution

The rebellion’s leaders included the husband-and-wife team Diego and Gabriella Silang. The couple are are well known in the Philippines today, where they are celebrated as heroes.

Diego Silang urged his followers to observe Lent. He encouraged fighting men to pray the Rosary, and prohibited them from getting drunk, having sex, or gambling on playing cards or cockfights during this sacred season. Silang was evidently trying to curry God’s favour through these collective sacrifices and devotions, hoping to secure a heavenly intervention that would protect his army and deliver them victory.

Like many Indigenous people in the islands, Silang would have also viewed asceticism in the Lenten season as a method of transferring power to people and to protective amulets known as anting anting[4], which they believed could potentially shield bodies from enemy cannon shot and arrows. Lots of different objects could be anting anting, including crucifixes and other religious medals or pieces of metal engraved with Catholic images, as well as pieces of paper inscribed with prayers. In this sense, Lent was the perfect time to spiritually prepare for revolution.

Convictions in such potent objects blended Filipino conceptions of power as a real force that could be physically accumulated in physical things, and European Catholic traditions of miraculous objects, including those that purport to cure sickness or protect soldiers in battle.

Christ the general

The Catholic character of the Silang rebellion manifests in other ways. Diego Silang declared that the life-sized wooden statue of Jesus Christ whose sanctuary was in Sinait was the general of the rebel army.

This was a famous miraculous statue. It sweated scented oils and cried salty tears, and locals believed it had ended devastating epidemics. These feats were inexplicable by the laws of nature and were therefore attributed to a divine agency. Silang’s followers fashioned a sceptre and small golden helmet for this image of Christ – symbols of military and political power in the islands – to acknowledge and honour its role in their war.

This statue of Jesus became a defining element of Silanista culture. Soldiers in the rebel Catholic army marched into battle under flags bearing its image. They also wore tiny carved copies of the statue tied to rope necklaces into battle.

The Silang rebellion[6] was ultimately defeated by force. Militant missionaries opposed the rebellion. Priests went on strike, denying Catholic sacraments to communities that supported the revolt. They also helped the Spanish government rally a huge loyalist army that beat the enemy in battle.

Loyalists also believed God was on their side. At the decisive battle of Vigan in Ilocos, the spires of churches appeared as the sails of tall ships carrying an army that was coming to defeat the rebels, terrifying them into submission. This was another miracle.

The Spanish empire would endure in the Philippines until 1898, when the United States invaded and supplanted Spain as the ruling colonial power.

Lent could inspire Catholic anti-colonial uprisings in the early modern Philippines, yet this special religious season also energised movements to destroy them.

References

- ^ rode into Sinait (www.loc.gov)

- ^ armed revolt (www.loc.gov)

- ^ Lent is here – remind me what it's all about? 5 essential reads (theconversation.com)

- ^ anting anting (en.wikipedia.org)

- ^ CC BY (creativecommons.org)

- ^ Silang rebellion (www.jstor.org)