an enzyme from bacteria can extract energy from hydrogen in the atmosphere

- Written by Chris Greening, Professor, Microbiology, Monash University

It may sound surprising, but when times are tough and there is no other food available, some soil bacteria can consume traces of hydrogen in the air as an energy source.

In fact, bacteria remove a staggering 70 million tonnes of hydrogen yearly from the atmosphere, a process that literally shapes the composition of the air we breathe.

We have isolated an enzyme that enables some bacteria to consume hydrogen and extract energy from it, and found it can produce an electric current directly when exposed to even minute amounts of hydrogen.

As we report in a new paper in Nature[1], the enzyme may have considerable potential to power small, sustainable air-powered devices in future.

Bacterial genes contain the secret for turning air into electricity

Prompted by this discovery, we analysed the genetic code of a soil bacterium called Mycobacterium smegmatis, which consumes hydrogen from air.

Written into these genes is the blueprint for producing the molecular machine responsible for consuming hydrogen and converting it into energy for the bacterium. This machine is an enzyme called a “hydrogenase”, and we named it Huc for short.

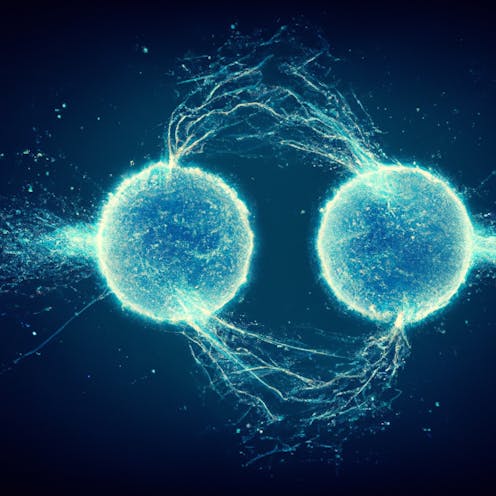

Hydrogen is the simplest molecule, made of two positively charged protons held together by a bond formed by two negatively charged electrons. Huc breaks this bond, the protons part ways, and the electrons are released.

In the bacteria, these free electrons then flow into a complex circuit called the “electron transport chain”, and are harnessed to provide the cell with energy.

Flowing electrons are what electricity is made of, meaning Huc directly converts hydrogen into electrical current.

Hydrogen represents only 0.00005% of the atmosphere. Consuming this gas at these low concentrations is a formidable challenge, which no known catalyst can achieve. Furthermore, oxygen, which is abundant in the atmosphere, poisons the activity of most hydrogen-consuming catalysts.

Isolating the enzyme that allows bacteria to live on air

We wanted to know how Huc overcomes these challenges, so we set out to isolate it from M. smegmatis cells.

The process for doing this was complicated. We first modified the genes in M. smegmatis that allow the bacteria to make this enzyme. In doing this we added a specific chemical sequence to Huc, which allowed us to isolate it from M. smegmatis cells.

Read more: Antarctic bacteria live on air and make their own water using hydrogen as fuel[2]

Getting a good look at Huc wasn’t easy. It took several years and quite a few experimental dead ends before we finally isolated a high-quality sample of the ingenious enzyme.

However, the hard work was worth it, as the Huc we eventually produced is very stable. It withstands temperatures from 80℃ down to –80℃ without activity loss.

The molecular blueprint for extracting hydrogen from air

With Huc isolated, we set about studying it in earnest, to discover what exactly the enzyme is capable of. How can it turn the hydrogen in the air into a sustainable source of electricity?

Remarkably, we found that even when isolated from the bacteria, Huc can consume hydrogen at concentrations far lower even than the tiny traces in the air. In fact, Huc still consumed whiffs of hydrogen too faint to be detected by our gas chromatograph, a highly sensitive instrument we use to measure gas concentrations.

We also found Huc is entirely uninhibited by oxygen, a property not seen in other hydrogen-consuming catalysts.

To assess its ability to convert hydrogen to electricity, we used a technique called electrochemistry. This showed Huc can convert minute concentrations of hydrogen in air directly into electricity, which can power an electrical circuit. This is a remarkable and unprecedented achievement for a hydrogen-consuming catalyst.

We used several cutting-edge methods to study how Huc does this at the molecular level. These included advanced microscopy (cryogenic electron microscopy) and spectroscopy to determine its atomic structure and electrical pathways, pushing boundaries to produce the most highly resolved enzyme structure yet reported by this method.

Enzymes could use air to power the devices of tomorrow

It’s early days for this research, and several technical challenges need to be overcome to realise the potential of Huc.

For one thing, we will need to significantly increase the scale of Huc production. In the lab we produce Huc in milligram quantities, but we want to scale this up to grams and ultimately kilograms.

However, our work demonstrates that Huc functions like a “natural battery” producing a sustained electrical current from air or added hydrogen.

As a result, Huc has considerable potential in developing small, sustainable air-powered devices as an alternative to solar power.

The amount of energy provided by hydrogen in the air would be small, but likely sufficient to power a biometric monitor, clock, LED globe or simple computer. With more hydrogen, Huc produces more electricity and could potentially power larger devices.

Another application would be the development of Huc-based bioelectric sensors for detecting hydrogen, which could be incredibly sensitive. Huc could be invaluable for detecting leaks in the infrastructure of our burgeoning hydrogen economy or in a medical setting.

In short, this research shows how a fundamental discovery about how bacteria in soils feed themselves can lead to a reimagining of the chemistry of life. Ultimately it may also lead to the development of technologies for the future.

References

- ^ a new paper in Nature (www.nature.com)

- ^ Antarctic bacteria live on air and make their own water using hydrogen as fuel (theconversation.com)

- ^ CC BY-NC (creativecommons.org)