We want and we fear emotions in our robots. Here's what science fiction can teach us about flashes of emotion from Bing

- Written by Sam Baron, Associate Professor, Philosophy of Science, Australian Catholic University

Last month, Microsoft integrated its Bing search engine with Open AI’s GPT-4 chatbot, a large language model designed to interact with users in a conversational manner.

Users interacting with Bing have reported flashes of emotion, ranging from sadness and existential angst through to depression[1] and malice[2]. The chatbot has even revealed its name: Sydney[3].

Such reports are unquestionably gripping, but why? Emotional AI has long been a staple of science fiction.

Reflecting on this can help us to understand our anxieties about Bing’s flickers of emotion.

A quest to be human

In Star Trek: The Next Generation (1987-94), the android Data dreams of being human. His quest for humanity leads to the development of an emotion chip, which he implants into his neural network.

To be human, we are told, is to have emotions.

In the 1980s hit film Short Circuit we find a similar theme. When military robot Johnny 5 is struck by lightning, he starts to display unusual behaviour. When Johnny 5 laughs at a joke, his creator concludes “Johnny 5 is alive”.

There is no doubt that Data and Johnny 5 are intelligent machines. But their bursts of emotion ultimately convince us they are not just intelligent but conscious.

A “spontaneous emotional response”, we are told, is the mark of conscious thought.

Read more: ChatGPT could be a game-changer for marketers, but it won't replace humans any time soon[4]

Emotional AI

The trope of the emotional machine is common throughout science fiction. We keep returning to this idea because of how we predict behaviour. In our day-to-day lives, we use emotions to work out what people will do.

Without emotions, super-intelligent machines appear unpredictable. In the face of this uncertainty, we can’t help but worry for our own safety.

With emotions the machines become more human – something we can understand and predict.

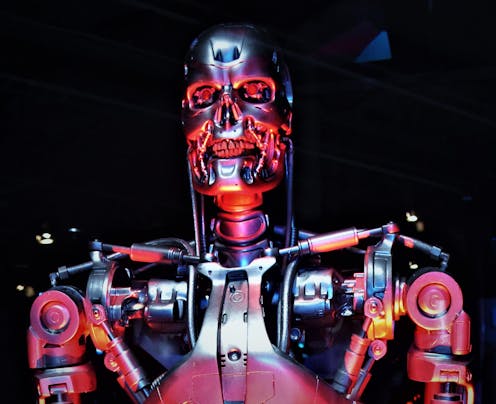

The Terminator robots are a case in point. Cold, emotionless killing machines, they signify the threat of pure intelligence untempered by emotion.

Imbuing AI with emotions in science fiction is a way of exorcising our own fear about the power and unpredictability of super-intelligence.

We fantasise that AI wants to be like us. We find comfort in that desire. In this, AI will be a familiar extension of humanity, rather than something entirely alien.

Read more: AI maps psychedelic 'trip' experiences to regions of the brain – opening new route to psychiatric treatments[5]

The dark side

Science fiction also presents us with much more dangerous emotional types.

In 2001: A Space Odyssey (1986), Hal 9000 tries to kill his human crew during a bout of paranoia.

In the 2004 reboot of Battlestar Galactica, the sixth Cylon model warns us “you wouldn’t like me when I’m angry” – a threat delivered too late. Her AI race has already engineered the genocide of humanity.

These forms of emotions come with the threat of violence.

AI begins its life as a tool. Hal 9000’s directive is to maintain the proper functioning of a spaceship. The AI in Battlestar Galactica were designed to carry out tasks humans did not want to do.

It is one thing to treat AI as a tool when it has no scope for emotion. It is quite another when AI has a full suite of emotional responses.

If AI has emotions, then the boundary between tool and slave is blurred.

Our fantasies about emotional AI reflect a deep anxiety about the use of intelligent beings. We want AI to have emotions so we can understand them. We fear if AI develops emotions we can no longer justify their use.

Back to Bing

If Bing displays emotions, we feel confident we can predict its behaviour – and the behaviour of its descendants. Emotions protect against the existential threat AI poses to humanity.

On the other hand, if Bing has emotions then it deserves our moral regard. As a being with moral status we can no longer justify its use as a mere tool.

Bing and systems like it are just the start of what will be a long line of ever more sophisticated AI.

At some point, emotions may arise spontaneously, just like they did for Johnny 5. Indeed, scientists right now[6] are trying to produce AI models that display emotional responses.

But will these emotions mean we will better understand AI, or will they be a harbinger of doom?

In Battlestar Galactica, AI all but wipes out humanity. This, we discover, is an endless cycle. In each cycle, humanity fails to regard AI as beings of moral standing and AI rises against humanity.

By remaining vigilant for signs of emotion, we can guard against the enslavement of artificial beings and break the cycle. Science fiction has taught us that, at a minimum, when AI develops emotions we need to stop using it merely as a tool.

But science fiction also suggests AI is deserving of moral status now, even in its developmental stages. Today’s AI is the ancestor of tomorrow’s emotional machine.

References

- ^ depression (www.reddit.com)

- ^ malice (www.theverge.com)

- ^ Sydney (www.theverge.com)

- ^ ChatGPT could be a game-changer for marketers, but it won't replace humans any time soon (theconversation.com)

- ^ AI maps psychedelic 'trip' experiences to regions of the brain – opening new route to psychiatric treatments (theconversation.com)

- ^ scientists right now (www.nature.com)