'Wellbeing'. It's why Labor's first budget will have more rigour than any before it

- Written by Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

What if the most important thing in Jim Chalmers’ first budget is the thing his critics are writing off as a gimmick?

Australia’s new treasurer has a lot on his plate. He has commissioned a complete review of the way the Reserve Bank works, he is drawing up a statement to parliament he says people will find “confronting[1]” and he is preparing the second of two budgets in one year; in October, updating the Coalition’s budget in March.

In what some see as a gimmick, it will be Australia’s first budget to benchmark its measures against their impact on the wellbeing of the Australian people: Australia’s first “wellbeing budget”.

Read more: Beyond GDP: Chalmers' historic moment to build wellbeing[2]

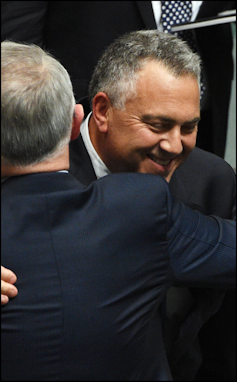

When Chalmers proposed the idea in opposition, the treasurer at the time, Josh Frydenberg, described it as “laughable[3]”.

Wellbeing was “doublespeak for higher taxes and more debt”.

Frydenberg asked parliament to imagine Chalmers delivering his first budget[4], the one he will deliver on October 25, “fresh from his ashram deep in the Himalayas, barefoot, robes flowing, incense burning, beads in one hand, wellbeing budget in the other”.

But here’s the thing. In an important way, Chalmers first “wellbeing budget” will have more rigour than any of the budgets prepared by Frydenberg or any of his predecessors.

It’ll be the first to have a stab at cost-benefit analysis.

Budgets are usually three things: a statement of accounts, with measures that will have an impact on the accounts (and sometimes measures that won’t[5]), as well as the legislation needed to authorise another year’s worth of expenditure.

What they don’t do, as a rule, is assess the impact of those measures, even the impact on the economy.

Measures without outcomes

Frydenberg’s first budget for example, in 2019, included a measure named “lower taxes for hard-working Australians[6]”.

The budget papers described what the measure would do and its impact on the budget, but not its impact on the economy.

The calculations may well have been carried out, but they weren’t included in the budget, as was typical. The budget papers told us what was being done, but not what it would do.

Until 2014 the budget papers at least told us who the budget would make better off and worse off. The standard table identified the impact of the budget as a whole on 17 different types of households at different types of incomes.

Prime Minister Tony Abbott and Treasurer Joe Hockey removed[7] it in their first budget, perhaps because they didn’t want the winners and losers to become apparent, and it hasn’t returned.

The budget papers neither tell us what the budget will do to economic growth, nor what it will do to incomes, nor what it will do to the environment or anything else other than the budget’s bottom line.

Which is a pity, because the budget is massive.

The government takes in just short of one quarter of all the dollars spent in Australia and pays out slightly more than one quarter of the dollars earned.

The balance between that income and spending is called the budget deficit or surplus. It matters, but so too does what that income and spending does.

Encompassing rather than replacing GDP

What Chalmers is proposing, and what New Zealand[8] and Scotland[9] are doing, and what Canada is working towards[10], is a scorecard of how budget measures affect the things that matter, including how much we produce: gross domestic product.

During the first Rudd government, Angela Jackson was deputy chief of staff to Finance Minister Lindsay Tanner. Reflecting on that time at last week’s Australian Conference of Economists[11], she said it was astounding that the expected effects of budget measures weren’t made explicit.

It meant what happened couldn’t be assessed against expectations.

Read more: Australia's wellbeing budget: what we can – and can't – learn from NZ[12]

Introducing measurables wouldn’t be about supplanting GDP, but about including it along with other measures of prosperity as outcomes against which the budget could be assessed, along with measures[13] of health, the environment, gender, children’s welfare, and the welfare of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

It would let us see whether we are making progress or going backwards on the environment (where we seem to be going backwards[14]) and on living standards, inequality, health and other things, and what the budget is doing about it.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics was on to this back in 2008 when it introduced a short-lived publication called Measures of Australia’s Progress[15] that reported on whether what came to be 26 key indicators were going forwards or backwards.

ABS Measures of Australia’s Progress 2013