the radical history of Australia's property market

- Written by Helen Dinmore, Research Fellow, University of South Australia

Skyrocketing property prices and an impossible rental market have seen growing numbers of Australians struggling to find a place to live.

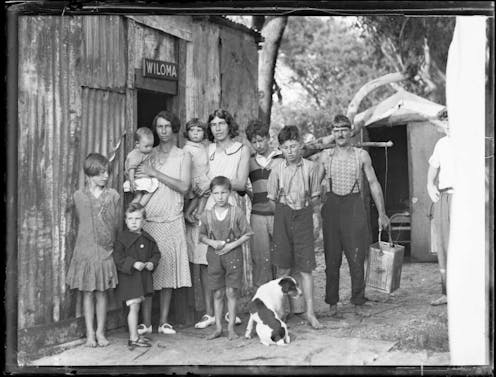

Recent images of families pitching tents or living out of cars evoke some of the more enduring scenes from the Great Depression. Australia was among the hardest hit countries when global wool and wheat prices plummeted in 1929.

By 1931, many were feeling the effects of long-term unemployment, including widespread evictions from their homes. The evidence was soon seen and felt as shanty towns – known as dole camps – mushroomed in and around urban centres across the country.

How we responded to that housing crisis, and how we talk about those events today, show how our attitudes about poverty, homelessness and welfare are entwined with questions of national identity.

Read more: 'I couldn't see a future': what ex-automotive workers told us about job loss, shutdowns, and communities on the edge[1]

Shanty towns and eviction riots

Sydney’s Domain, Melbourne’s Dudley Flats and the banks of the River Torrens in Adelaide were just a few places where communities of people experiencing homelessness sprung up[2] in the early 1930s.

Some lived in tents[3], others in makeshift shelters of iron, sacking, wood and other scavenged materials. Wooden crates, newspapers and flour and wheat sacks were put to numerous inventive domestic uses, such as for furniture and blankets. Camps were rife with lice, fevers and dysentery, all treated with home remedies.

But many Australians fought eviction from their homes in a widespread series of protests and interventions known as the anti-eviction movement[5].

As writer Iain McIntyre outlines in his work Lock Out The Landlords: Australian Anti-Eviction Resistance 1929-1936[6], these protests were an initiative of members of the Unemployed Workers Movement – a kind of trade union of the jobless.

As explained[7] by writers Nadia Wheatley and Drew Cottle,

With the dole being given in the form of goods or coupons rather than as cash, it was impossible for many unemployed workers to pay rent. In working class suburbs, it was common to see bailiffs dumping furniture onto the footpath, pushing women and children onto the street. Even more common was the sight of strings of boarded up terrace houses, which nobody could afford to rent. If anything demonstrated the idiocy as well as the injustice of the capitalist system it was the fact that in many situations the landlords did not even gain anything from evicting people.

The Unemployed Workers Movement goal[8] was to

Organise vigilance committees in neighbourhoods to patrol working class districts and resist by mass action the eviction of unemployed workers from their houses, or attempts on behalf of bailiffs to remove furniture, or gas men to shut off the gas supply.

Methods of resistance were varied in practice. Often threats were sufficient[9] to keep a landlord from evicting a family.

If not, a common tactic[10] was for a large group of activists and neighbours to gather outside the house on eviction day and physically prevent the eviction. Sometimes this led to street fights with police[11]. Protestors sometimes returned[12] in the wake of a successful eviction to raid and vandalise the property.

Protestors went under armed siege in houses barricaded with sandbags and barbed wire. This culminated in a series[13] of bloody battles with police in Sydney’s suburbs in mid-1931, and numerous arrests.

It’s not just what happened – it’s how we talk about it

Narratives both reflect and shape our world. Written history is interesting not just for the things that happened in the past, but for how we tell them.

Just as the catastrophic effects of the 1929 crash were entwined with the escalating struggle between extreme left and right political ideologies, historians and writers have since taken various and even opposing viewpoints when it comes to interpreting the events of Australia’s Depression years and ascribing meaning to them.

Was it a time of quiet stoicism that brought out the best in us as “battlers” and fostered a spirit of mateship that underpins who we are as a nation?

Or did we push our fellow Australians onto the streets and into tin shacks and make people feel ashamed for needing help? As Wendy Lowenstein wrote in her landmark work of Depression oral history, Weevils in the Flour[14]:

Common was the conviction that the most important thing was to own your own house, to keep out of debt, to be sober, industrious, and to mind your own business. One woman says, ‘My husband was out of work for five years during the Depression and no one ever knew […] Not even my own parents.’

This part of our history remains contested and narratives from this period - about “lifters and leaners” or the Australian “dream” of home ownership, for example – persist today.

As Australia’s present housing crisis deepens, it’s worth highlighting we have been through housing crises before. Public discussion about housing and its relationship to poverty remain – as was the case in the Depression era – emotionally and politically charged.

Our Depression-era shanty towns and eviction protests, as well as the way we remember them, are a reminder that what people say and do about the housing crisis today is not just about facts and figures. Above all, it reflects what we value and who we think we are.

References

- ^ 'I couldn't see a future': what ex-automotive workers told us about job loss, shutdowns, and communities on the edge (theconversation.com)

- ^ sprung up (catalogue.nla.gov.au)

- ^ lived in tents (catalogue.nla.gov.au)

- ^ Knights, Bert/State Library of Victoria (search.slv.vic.gov.au)

- ^ anti-eviction movement (commonslibrary.org)

- ^ Lock Out The Landlords: Australian Anti-Eviction Resistance 1929-1936 (commonslibrary.org)

- ^ explained (rahu.org.au)

- ^ goal (rahu.org.au)

- ^ sufficient (rahu.org.au)

- ^ tactic (rahu.org.au)

- ^ police (commonslibrary.org)

- ^ returned (catalogue.nla.gov.au)

- ^ series (www5.austlii.edu.au)

- ^ Weevils in the Flour (catalogue.nla.gov.au)