If governments were really concerned about tax and the cost of living they would cut the cost of childcare

- Written by Miranda Stewart, Professor, The University of Melbourne

Amid the talk about tax changes set to cut the middle-income rate to 30%[1], a shortage of workers[2] and incomes not keeping up with the cost of living[3], one common threat shines through.

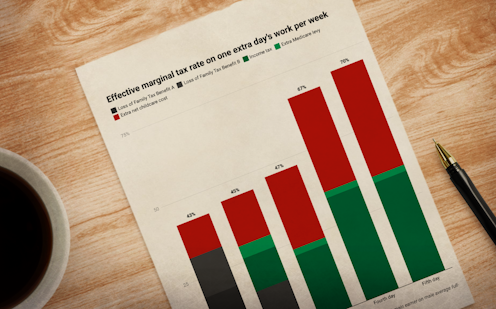

It’s the cost of childcare, which, according to new calculations, imposes an effective tax as high as 70% on a second-earner wanting to work a fourth or fifth day a week.

The example in this chart is for a family on average male and female wages with two children under five, whose mother is considering working an extra day.

Such a mother with two children needing childcare would lose 32% of her first day’s wage in reduced family tax benefits, and a further 11% in childcare fees (net of subsidy) amounting to an effective marginal tax[4] of 43%.

On her second day she would also pay tax (earning above the tax free threshold[5]), and on her third day would lose 47% of her earnings, made up of 23% in tax and 24% in extra net childcare fees.

If she worked a fourth day, this would jump to 67% of that day’s earnings, made up of 36% in tax and 31% in extra net childcare fees.

Read more: Blink and you'll miss it: what the budget did for working mums[6]

If she worked a fifth day, the impost would climb to 70% of that day’s earnings, made up of 35% in tax and 35% in extra net childcare fees.

The 67% and 70% effective marginal tax rates are severe, and beyond what we would normally consider to be a reasonable take from a day’s pay packet.

More women could be working

In the past few months the proportion of working-age Australian women in paid work has climbed to a record high of 60%[7], but it remains well below that in some of the countries to which we normally compare ourselves, including New Zealand in which 64.2%[8] of working-age women are in paid work.

If Australia’s rate of female employment was lifted to New Zealand’s, an extra 460,000 Australian women would be in paid work.

Employed women in Australia are more likely to work part time[9] than employed women in any other member of the 38-nation OECD apart from Japan, Switzerland and the Netherlands.

It’s childcare that holds women back

Asked why they are unable to work more hours, almost half the women surveyed by the Australian Bureau of Statistics nominate “caring for children[10]”.

Asked to nominate the incentive that would do the most to help them work more hours, half pick “access to childcare[11]”.

The high cost of childcare steers women away from full-time work toward the role of primary caregiver at home. This in turn limits their career progression, their economic security, their retirement savings and their ability to afford housing.

It is also likely to limit fertility, which has fallen to 1.6[12], well below replacement levels, and limits tax revenue and Australia’s access to skills.

Employers are crying out for workers

Job vacancies are at a record high[13] with employers crying out[14] for skilled workers.

An analysis prepared for Chief Executive Women[15] found that if women’s employment reached that of men’s, an extra one million full-time equivalent workers would become available, 800,000 of them with diplomas or more.

Separate modelling prepared for the National Foundation for Australian Women[16] finds that expanding the provision of childcare (including by lifting the wages of childcare workers) would boost Australia’s labour supply 2%.

After ten years it would boost gross domestic product 1.6%[17].

Minor progress

In response to sustained calls for reform, the government last year boosted[18] the childcare subsidy for families with two or more children in childcare, and removed the annual subsidy cap.

Read more: How the Coalition's child-care subsidy plan works and what it means[19]

While addressing some of the most egregious effective marginal tax rates, these changes have not brought down the high costs for workers on average wages.

Labor[20] and the Greens[21] have promised to cut childcare costs. The so-called teal[22] independents are also campaigning on the issue.

To work, such policies will need to be backed by an investment in the pipeline of childcare workers.

References

- ^ 30% (theconversation.com)

- ^ shortage of workers (theconversation.com)

- ^ cost of living (theconversation.com)

- ^ effective marginal tax (taxpolicy.crawford.anu.edu.au)

- ^ tax free threshold (www.ato.gov.au)

- ^ Blink and you'll miss it: what the budget did for working mums (theconversation.com)

- ^ 60% (www.abs.gov.au)

- ^ 64.2% (www.stats.govt.nz)

- ^ part time (data.oecd.org)

- ^ caring for children (www.abs.gov.au)

- ^ access to childcare (www.abs.gov.au)

- ^ 1.6 (www.abs.gov.au)

- ^ record high (www.abs.gov.au)

- ^ crying out (www.hcamag.com)

- ^ Chief Executive Women (cew.org.au)

- ^ National Foundation for Australian Women (nfaw.org)

- ^ 1.6% (nfaw.org)

- ^ boosted (theconversation.com)

- ^ How the Coalition's child-care subsidy plan works and what it means (theconversation.com)

- ^ Labor (www.alp.org.au)

- ^ Greens (greens.org.au)

- ^ teal (www.afr.com)