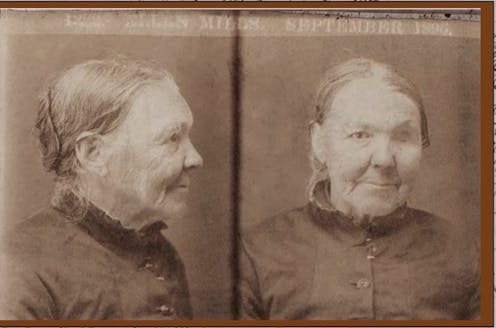

'the Buzzwinker' Ellen Miles, child convict, goldfields pickpocket and vagrant

- Written by Janet McCalman AC, Emeritus Redmond Barry Distinguished Professor, The University of Melbourne

—Me name’s Miles; Ellen Miles, remarked an old woman at the City Court yesterday.

—And you are charged with vagrancy, stated Sergeant Eason. Can you show the Bench that you have means of support?

—'How can I support myself when I’m continually in gaol and not a shilling coming into the house? What is it at all? What are us old people to do? There is no institution in the country,’ replied Mrs Miles.

—Sergeant Eason: But the country has been keeping you for years.

—Mrs Miles: ‘What! the country supporting me. Why, I’m supporting the country. I’ve scattered my money over the colony for the last 50 years. To tell the truth, I’ve spent thousands and thousands of pounds.

Accused, who was found sitting on the hospital steps in Little Lonsdale street, late at night, with a bandage over her eye nearly as large as a pillow, was sentenced to three months, as was also a companion named Bridget Jones.

It was October 1896 and the accused, Ellen Miles, was almost 70 years old. She had indeed been scattering her money across the colony for 50 years. She would live for another 20, still in and out of gaol and benevolent asylums, until she was too frail to escape the Ballarat institution where she died in 1916.

This was fitting, as it was the Ballarat diggers who years before had dubbed her the “Buzzwinker”, an elaboration of the cant for pickpocket. Later, a locomotive from the Phoenix foundry that moved with a “pronounced waddle” was named Buzzwinker after her[1]. She matters to us today because hers is a rare and unmediated voice from the criminal underclass of Vandemonian women.

She was a child of the 1830s and lived until 1916. How aware she ever was of the Great World outside her tiny one of back lanes, brothels and bars, we have no idea, but her life spanned the history of Victoria from the discovery of gold to Gallipoli.

She did register to vote in 1903, but hers was an underlife as she waddled around Canvas Town, Romeo Lane, the gold fields, Collingwood – and for one mad adventure, to Adelaide, her copious skirts concealing her latest stolen goods. Wherever there was a lurk to exploit and a lark to celebrate, Ellen was there.

'Notorious utterers’

Her first appearance in the press had been in 1839: Ellen Miles, aged 11, was charged at the Guildhall with passing a counterfeit half-crown to a shopkeeper in Russell Street, Bloomsbury, London. Mr Field, an inspector at the Mint, said that this child was “one of three sisters, all notorious utterers”.

Ellen had already been in custody 30 times and sported three aliases. Her mother was dead. Her father claimed[3] he could not control her and that it might be an act of mercy to transport her. As predicted, her second appearance at the Old Bailey in October resulted in transportation.

Her sister Ruth, when before the Old Bailey herself a few months later, gave the game away: their father, Moses Miles, a costermonger (street trader), wanted all his girls transported so as to be relieved of their support. It was he who gave them the counterfeit coins to pass. His daughters had been in and out of St Pancras Workhouse since 1833, when Ellen was six. She graduated at the age of ten after 14 months in the Children’s Ward on her own.

It was there that she may have learnt to read and write, and it was there, among the toughest, roughest females in London, that she learned to survive. Both sisters were fierce, voluble and violent. They followed each other to Van Diemen’s Land: Ellen transported on the Gilbert Henderson in 1839, sentenced to seven years, Ruth five months later aboard the Navarino, with a sentence of 15.

Ellen had her first experience of solitary confinement six months after arrival. She continued to be insolent and to disobey orders. In July 1841, aged 13, she was punished for being in the company of a Richard Nichols. In May 1842, six months was added to her sentence for absconding.

Wild nights behind bars

Two months later in July 1842, she was convicted of riot and breaking a table in the Launceston Female Factory, together with Mary Sheriff and Catherine Lowry, two notorious members of the “flash mob[4], who:

always had money, wear worked cap, silk handkerchiefs, earrings and other rings they are the greatest blackguards in the building. The other women were afraid of them. They led away the young girls by bad advice.

To have a good time was to keep offending and remain under punishment in the Female Factory, where the women, once locked in at night, could sing and be as lewd as they liked. They could dance naked and have sex[5] with other women — women they loved and women they bullied.

In January 1852, with her only child dead and her husband, a fellow Cockney, in tow, she was off to gold-rush Melbourne, bedecked in ribbons and ready to make her fortune from the befuddled diggers seeking sex and oblivion. Hers was a public life, lived in open sight of the world. Rarely in her long life did she have a home outside gaol.

Read more: Hidden women of history: how 'lady swindler' Alexandrina Askew triumphed over the convict stain[6]

On the town

She slept where she found shelter: in corners of cottages, huts, shanties, outhouses, stables, public houses; in gutters and lanes, and on the banks of the Yarra. She ate where she could and drank whenever she could afford it.

She would rarely have used a privy, instead relieving herself in the street. She bathed mostly in gaol. Her clothes, probably stolen, lasted until they fell off her in rags. When she was arrested in Little Lonsdale Street, she had that bandage "the size of a pillow over one eye” and soon lost the eye completely. She sought invisibility from the law by changing her name, story and religion at whim.

She never admitted she was a transported convict, but claimed she had accompanied her long-deceased mother on the Gilbert Henderson. She generated criminal records under the names Buzzwinker, Ellen Watkins, Ellen Miles, Ann Myles, Ann Watkins, Ellen Burns, Ellen Grimes, Ellen Johnson and Bridget Brady. She did, at one stage, even claim Spanish birth.

She delivered her final words for posterity in December 1902. Charged under the name of Bridget Brady, born in Ireland and of the Catholic faith, she quickly protested her real self and her good character:

—Bridget Brady at all. My name is Ellen Watkins and I am a decent woman.

Sergeant Eason — Oh we know all about you, Bridget, you’ve been convicted of all sorts of offences—nine times larceny, six times soliciting.

This was too much for Ellen:

—Soliciting is it? And I’m 82 (Laughter) Tis many a year since I was soliciting, I’m thinking. (Laughter).

Sergeant Eason—Yes, the record goes back over thirty years.

Brady (contemptuously)—Thirty grandmothers (Laughter). Why it must be full sixty years ago man. (Laughter)

Accused was sentenced to six months’ imprisonment.

References

- ^ named Buzzwinker after her (railstory.org)

- ^ CC BY (creativecommons.org)

- ^ father claimed (www.oldbaileyonline.org)

- ^ “flash mob (www.femaleconvicts.org.au)

- ^ dance naked and have sex (www.femaleconvicts.org.au)

- ^ Hidden women of history: how 'lady swindler' Alexandrina Askew triumphed over the convict stain (theconversation.com)