the costs of Morrison's voter ID plan outweighed any benefit

- Written by John Quiggin, Professor, School of Economics, The University of Queensland

The Morrison government has shelved its plan to make Australians produce identification before casting their vote. Yesterday it withdrew the Electoral Legislation Amendment (Voter Integrity) Bill 2021[1] it had hoped to pass in time for the 2022 election.

The reason is political. The announcement came hours after Tasmanian independent senator Jacqui Lambie said[2] she would vote against the bill.

With rebel Coalition backbenchers in both the House of Representatives and Senate vowing to vote against all legislation in a bid to force the Morrison government’s hand on vaccine mandates, it reportedly did a deal[3] with the Opposition to drop the bill in return for Labor supporting another bill, to oblige charities to reveal donors.

But it should have dropped the bill as a matter of good policy.

There are various ways in which such proposals might be analysed, but an economic framework of cost-benefit analysis would be a useful starting point. As the name implies, the aim is to weigh up the potential benefits of a policy to determine if they outweigh the costs.

The Australian government says it is[4] “committed to the use of cost–benefit analysis to assess regulatory proposals in order to encourage better decision making”. Had it done a cost-benefit analysis of the bill, it’s hard to see how it could have introduced it in the first place.

Benefits of identification

Let’s start with the benefits.

The strongest argument for voter ID is to prevent impersonation – one person voting in the name of another. In Australia, however, voting is compulsory, which makes impersonation hard to accomplish.

About 95% of registered voters normally vote in elections.

To effectively impersonate another voter without producing an apparent double vote, a fraudster would have know who the non-voters were. There is some anecdotal evidence[5] that people do sometimes vote on behalf of a friend. But while this is illegal, such proxy votes are unlikely to change the result.

Because of votes are checked against the electoral roll, we have good evidence on the extent of multiple voting in Australia.

After the 2016 election, the Australian Electoral Commission identified 18,343 instances[6] where a name had been crossed off twice – about 0.12% of the 14.89 million votes[7] cast.

Investigating a sample of these, the AEC found nearly 80% were most likely errors by it own staff, such as crossing off the name above or below the correct one on the electoral roll.

Another 10% were mistakes by voters, who might have been mentally ill, confused because of language issues, or who simply forgot they had already voted.

That left about 1,800 votes (0.012% of votes cast) where there was no obvious explanation. But also no compelling evidence of deliberate multiple voting.

The strongest evidence came from 59 cases where three votes were cast under the same name, including one person who apparently voted 16 times[8].

A requirement to show ID would not prevent someone from voting multiple times if they chose to do so. But it might facilitate prosecution by making it impossible for a multiple voter to claim that someone else voted in their name.

However, the AEC’s data suggest the total number of excess votes here amounts to two or three per electorate. With about 100,000 voters per electorate, this is nowhere near enough to make any real difference.

Voter ID would prevent someone from voting on behalf of another with their consent. There is anecdotal evidence that this happens, but not on a large scale, and we would expect the real voter would choose someone who they trust to lodge a vote according to their wishes.

Now let’s look at the costs.

Administrative costs

A voter ID proposal has two kinds of costs.

First, there are the costs of ID checking: administrative costs for the electoral commission and the compliance cost for voters who have to ensure they have ID.

Australia’s only previous experience with voter ID laws is in Queensland. The Liberal National Party government led by Campbell Newman introduced an ID requirement in 2014[9]. This was in force for the 2015 state election, in which the LNP was narrowly defeated. The incoming Labor government repealed it.

In that election, the Electoral Commission of Queensland mailed every voter a card they could use to vote. This was the predominant method used, and made compliance easier. But presumably it cost hundreds of thousand of dollars in postage and administration.

Moreover, since the cards had no photo they didn’t provide any security against consensual vote impersonation. There was nothing to stop someone who didn’t feel like voting giving their card to a friend.

The big cost, though, lies in the possibility that some people would be discouraged from voting or would be refused a vote because of inadequate ID. Even if the Queensland card scheme is emulated, there’s a chance of voters failing to receive their card or misplacing it.

Turnout fell at the Queensland 2015 election, but we can’t necessarily draw any sharp conclusions about the role ID laws may have played because there was a further decline in 2017. The likelihood of these laws disenfranchising the poor, homeless and vulnerable, however, does appear quite high.

Read more: Why voter ID requirements could exclude the most vulnerable citizens, especially First Nations people[10]

Effects on trust

Beyond these direct costs and benefits, it is important to consider the effects of ID laws on our political culture as a whole.

Some proponents of ID laws have argued[11] they will increase public confidence in the electoral system.

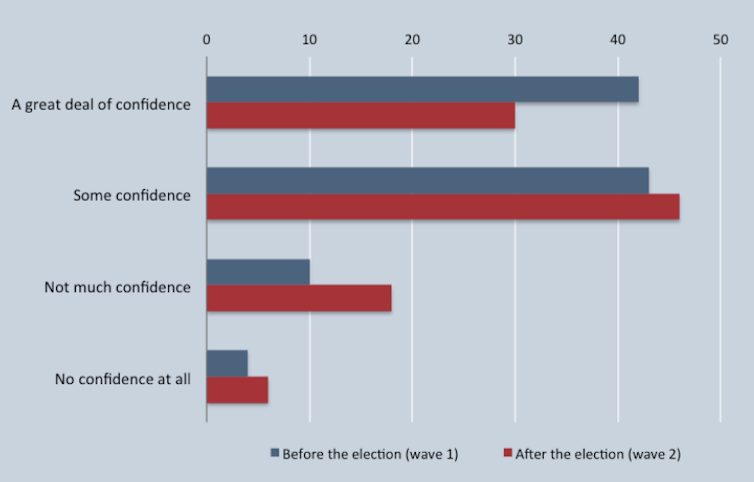

That might be the case if there were widespread concern about closely contested elections. A 2017 study[12] by University of Sydney and Harvard researchers found about one in four Australian believe fraud occurs “usually” or “always” in elections. But there’s no real evidence to suggest voter ID laws would ease these doubts.

Confidence in the AEC’s ability to conduct an election