Menstrual cups are a cheaper, more sustainable way for women to cope with periods than tampons or pads

- Written by Susan Powers, Spence Professor of Sustainable Environmental Systems and the Director of the Institute for a Sustainable Environment, Clarkson University

Every year in America, women spend at least US$2.8 billion on sanitary pads and tampons[1] that can take hundreds of years to decompose[2]. Is there a more economical and environmentally friendly way? To find out, we asked Susan Powers[3], a professor of sustainable environmental systems at Clarkson University about her work comparing the environmental impact of tampons, sanitary pads and menstrual cups.

What is a menstrual cup?

A menstrual cup[4] is a type of reusable feminine hygiene product. It’s a small, flexible bell-shaped cup made of rubber or silicone that a woman inserts into her vagina to catch and collect menstrual fluid. It can be used for up to 12 hours, after which it is removed to dispose of the fluid and cleaned. The cup is rinsed with hot water and soap between each insertion and sterilized in boiling water at least once per period. A cup can last up to 10 years[5].

Although menstrual cups have been around for decades, they historically have been less popular[6] than pads or tampons.

Are menstrual cups growing in popularity?

Yes[7], their popularity is growing as women, as well as men, become more comfortable dealing with and discussing menstruation. They have been a topic in news media ranging from Teen Vogue[8] to NPR[9]. Another part of their growing popularity stems from the general public’s concern about solid waste[10] associated with any disposable product, including disposable pads and tampons.

You have been researching the life cycle of different feminine hygiene products. What is a life cycle assessment and what have your studies shown?

A life cycle assessment[11] provides a broad accounting and evaluation of all of the materials, energy and processes associated with the raw materials in a product, including their extraction, manufacture, use and disposal. Impacts considered include climate change, natural resource depletion, human toxicity and ecotoxicity, among others.

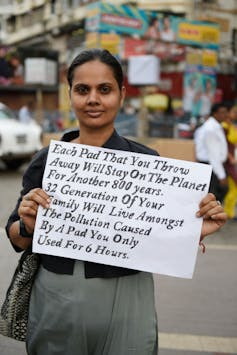

A woman in India holds a sign to raise awareness about using eco-friendly menstrual cups instead of sanitary pads.

Indranil Aditya/NurPhoto via Getty Images[12]

A woman in India holds a sign to raise awareness about using eco-friendly menstrual cups instead of sanitary pads.

Indranil Aditya/NurPhoto via Getty Images[12]

I have worked for several years on a range of these assessments[13] for consumer products and energy and agricultural systems. When Clarkson Honors Program student Amy Hait approached me about her idea of completing a life cycle assessment on feminine hygiene products, I was intrigued and happy to work closely with her to complete the study and publish the results in the journal Resources, Conservation & Recycling[14].

We compared three products: a rayon-based tampon[15] with a plastic applicator, a maxipad with a cellulose and polyethylene absorbent core[16] and a menstrual cup made of silicone[17].

The assessment also included packaging materials and the processes to make and transport these materials. In order to make a fair comparison among products, we looked at the number of products used by an average woman in one year. Based on published average values[18], that would be 240 tampons or maxipads. A menstrual cup has a 10-year lifespan, so its use for one year is the equivalent of one-tenth of the overall manufacturing and disposal impact.

Our assessment included eight different categories to evaluate the overall environmental impact. These include measuring the impacts on the environment and human health.

The life cycle impact assessment provides quantitative scores for the impacts of each of these individually. We also used normalization factors for the United States to enable us to come up with a total impact score. Higher scores reflect greater overall impacts.

Is using a menstrual cup more environmentally sustainable?

The results of the life cycle assessment clearly showed that the reusable menstrual cup was by far the best based on all environmental metrics. Based on the total impact score, the maxipad we considered in our study had the highest score, indicating higher impacts. The tampon had a 40% lower score and the menstrual cup 99.6% lower. The key factor for the high score for the maxipad was its greater weight and the manufacture of the raw materials to make it.

Most people choose a reusable product because they believe it won’t add waste to landfills. But our study shows that most environmental benefits are from the reduced need to prepare all of the raw materials and manufacture the product.

Taking the tampon as an example, the extraction and preparation of the raw materials used to make it contributed over 80% of the total impact. Disposal, which people often pay more attention to, really contributes substantially only to water pollution, which is a very minor component of the overall impact.

The life cycle assessment also identifies sometimes surprising sources of environmental and health impacts, including dioxins from bleaching wood pulp for pads, zinc from rayon production for tampons and chromium emissions from fossil fuel energy sources. By not having to produce more single-use products, we can avoid emitting many of these pollutants.

[Get the best of The Conversation, every weekend. Sign up for our weekly newsletter[19].]

As with any other consumer goods, the impacts associated with the manufacture and disposal of products are greatly reduced the more times you reuse anything. Using a reuseable cup for even just one month instead of the average 20 pads or tampons was still an environmentally preferable approach.

What is done to encourage the use of a more sustainable feminine hygiene product?

The taboo nature of talking about menstruation is changing with young women, at least in the United States. Women at Clarkson University, for example[20], worked with a cup manufacturer to provide a very public giveaway program to distribute free cups to over 100 college students. That would never have happened when I was a student decades ago. Many health-related web sites like WebMD[21] and Healthline[22] provide relevant and reliable information on the proper use and care of menstrual cups, which should help to reduce concerns over their use and encourage more women to try them.

References

- ^ US$2.8 billion on sanitary pads and tampons (www.statista.com)

- ^ hundreds of years to decompose (www.nationalgeographic.com)

- ^ Susan Powers (www.clarkson.edu)

- ^ menstrual cup (www.healthline.com)

- ^ up to 10 years (doi.org)

- ^ less popular (www.theguardian.com)

- ^ Yes (www.globenewswire.com)

- ^ Teen Vogue (www.teenvogue.com)

- ^ NPR (www.npr.org)

- ^ general public’s concern about solid waste (www.forbes.com)

- ^ life cycle assessment (ecochain.com)

- ^ Indranil Aditya/NurPhoto via Getty Images (www.gettyimages.com)

- ^ range of these assessments (www.clarkson.edu)

- ^ publish the results in the journal Resources, Conservation & Recycling (doi.org)

- ^ rayon-based tampon (www.ubykotex.com)

- ^ maxipad with a cellulose and polyethylene absorbent core (www.ubykotex.com)

- ^ menstrual cup made of silicone (divacup.com)

- ^ published average values (www.huffpost.com)

- ^ Sign up for our weekly newsletter (theconversation.com)

- ^ Women at Clarkson University, for example (www.facebook.com)

- ^ WebMD (www.webmd.com)

- ^ Healthline (www.healthline.com)