How the terrifying evacuations from the twin towers on 9/11 helped make today's skyscrapers safer

- Written by Erica Kuligowski, Vice-Chancellor's Senior Research Fellow, RMIT University

The 2001 World Trade Center disaster was the most significant high-rise evacuation in modern times, and the harrowing experiences of the thousands of survivors who successfully escaped the twin towers have had a significant influence on building codes and standards. One legacy of the 9/11 tragedy is that today’s skyscrapers can be emptied much more safely and easily in an emergency.

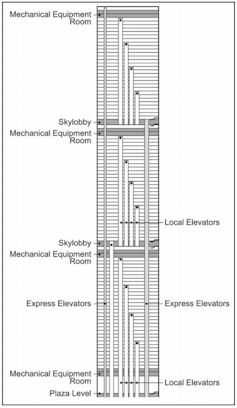

The twin towers’ elevator layouts meant getting to ground level was more complicated on some floors than on others.

US NIST

The twin towers’ elevator layouts meant getting to ground level was more complicated on some floors than on others.

US NIST

The 110-storey twin towers, constructed from 1966 to 1973, both had open-plan floor designs, with stairs and elevators located in the buildings’ core. Each tower had three staircases which, barring a few twists and turns, ran all the way from the top of the building down to the mezzanine level just above the ground floor. One of the stairways had steps 142 centimetres wide, but the other two measured just 112cm, which would not be permitted by today’s skyscraper building codes.

As a result of the twin towers’ system of “sky lobbies[1]”, which was innovative for its time, the number of available elevators varied depending on the floor. The system was not designed to be used in an emergency, and today, many towers above a certain height are required to be fitted with dedicated emergency elevators or an additional staircase.

When the planes hit on the morning of September 11 2001, the twin towers were at less than half their full occupancy, with about 9,000 people in each tower[2]. Many people who worked there had not yet arrived, partly because of a New York mayoral election scheduled for that day.

At 8:46am, American Airlines flight 11 slammed into the north face of the north tower, rendering all three staircases impassable for anyone above the 91st floor. Sixteen minutes later, and after one-third of its occupants had already evacuated, the south tower was hit by United Airlines flight 175, leaving only one staircase available for evacuees above the 78th floor.

Besides the problems posed by fires and damage on floors, and debris inside the stairways, people in both towers also faced issues with communication. The north tower’s public address system, which would have been used to make emergency announcements to the building’s occupants, was disabled by the crash.

In the south tower, three minutes before the impact, occupants were told via the public address system to stay in place and wait for further information. Two minutes later they were told they could evacuate if they wanted. This may have meant more people from higher floors were waiting at the sky lobby on floor 78 when the plane crashed into that floor.

Read more: 9/11 conspiracy theories debunked: 20 years later, engineering experts explain how the twin towers collapsed[3]

In both towers, people had only limited information on which to base their decisions. For those closest to the impacts, the seriousness of the situation and the need to evacuate was clear. But for those further away, who may have witnessed only the lights flicker, the uncertainty was palpable. Many people delayed their evacuation to seek out extra information, whether by speaking with colleagues, making phone calls, sending emails or searching online for news updates.

Many lives were saved by the brave leadership of people who took control of the situation, urging others to evacuate and helping those who needed assistance. My PhD research[4] revealed these were typically people who were used to taking charge: high-level managers, fire wardens and people with military experience.

Hazardous exit

Evacuees faced a dangerous and claustrophobic journey down to ground level. A subsequent US government investigation[5] found 70% of evacuees encountered crowding on the stairs. Some people recalled having to leave the stairwell either because of overcrowding, being told to do so by fire or building officials, or because they needed a rest. Other problems included poor lighting, not knowing which direction to go, and finding the route unavoidably blocked by people with permanent or temporary disabilities.

One of the narrow staircases in the north tower, taken during the evacuation on September 11 2001.

NIST

One of the narrow staircases in the north tower, taken during the evacuation on September 11 2001.

NIST

While people are typically told not to use elevators in an emergency, 16% of those who escaped the south tower used the elevators to evacuate during the 16 minutes between the two impacts. Simulations[6] of a hypothetical 9/11 in which elevators were unavailable showed that occupants’ use of elevators saved 3,000 lives in the south tower.

Not everyone was so lucky. The US National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) investigation[7] (on which I was an author) estimated that between 2,146 and 2,163 people were killed in the towers, and that more people died in the north tower, which was struck first. Most of those who died on 9/11 were on or above the floors hit by the planes.

Roughly 99% of people on floors below the impacts managed to evacuate successfully. For those who didn’t, the factors linked to their deaths included delaying their evacuation, performing emergency response duties, or being unable to leave their particular floor because of damage or debris. Had the buildings been fully occupied, the consequences would undoubtedly have been even worse.

Read more: 20 years on, 9/11 responders are still sick and dying[8]

Building better

The stories of those who experienced the terrifying evacuations have helped to shape important and life-saving changes in high-rise buildings. The NIST report[9] made several recommendations that were eventually implemented in a range of building codes and standards around the world, notably the International Building Code[10].

Emergency stairs in skyscrapers must now be at least 137cm wide, and feature glow-in-the-dark markings on the stair treads that are visible even if the power fails.

Stairwells in large buildings are now wider and have better signage.

Rico Shen/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA[11]

Stairwells in large buildings are now wider and have better signage.

Rico Shen/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA[11]

What’s more, while elevator use is not typically encouraged during building fires, the International Building Code now requires a new “occupant-safe” elevator system or an additional staircase in buildings over 128 metres tall. These new elevator systems are designed to be safely used during fires, offering a vital escape route for people unable to use stairs.

The tragic events of 9/11 changed the world in all sorts of ways. But hopefully, when it comes to the design of today’s skyscrapers, it has changed things for the better.

References

- ^ sky lobbies (skyrisecities.com)

- ^ about 9,000 people in each tower (www.nist.gov)

- ^ 9/11 conspiracy theories debunked: 20 years later, engineering experts explain how the twin towers collapsed (theconversation.com)

- ^ PhD research (scholar.colorado.edu)

- ^ subsequent US government investigation (www.nist.gov)

- ^ Simulations (link-springer-com.ezproxy.lib.rmit.edu.au)

- ^ US National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) investigation (www.nist.gov)

- ^ 20 years on, 9/11 responders are still sick and dying (theconversation.com)

- ^ NIST report (www.nist.gov)

- ^ International Building Code (www.iccsafe.org)

- ^ CC BY-SA (creativecommons.org)