From October, it will be all but impossible for most Australians to vape — largely because of Canberra's little-known 'homework police'

- Written by Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

After a misstep, it’s about to become illegal to import e-cigarettes without a prescription, which means that, for most Australians, it’ll become all but impossible to vape from October 1.

The misstep tells us a lot about how the Australian government works behind the scenes — most of it good.

Mid last year, Health Minister Greg Hunt announced plans to ban[1] the import of nicotine-containing e-cigarettes and refills without a doctor’s prescription. Border force would be checking parcels.

To Hunt, the decision made sense. It was already illegal to buy and sell such products without a prescription in every Australian state and territory, and it was illegal to possess them without a prescription in every state but South Australia.

All Hunt was doing was closing a (very wide) loophole.

Government backbenchers revolted[2], Hunt pointed to a doubling of nicotine poisonings over the past year and the death of a toddler, the prime minister offered less than complete support, saying he was keeping an “open mind”, and Hunt put the idea on the backburner[3].

That’s the way it played out in public.

But beneath the surface, something impressive was swinging into gear. It’s called the Office of Best Practice Regulation, OBPR[4], an apolitical body nestled within the prime minister’s department.

Canberra’s ‘homework police’

So what did this little-known part of the government do that will effectively stamp out vaping from next month? Its executive director, Jason Lange, revealed the back story at an Economic Society of Australia meeting in Canberra earlier this year[5].

Set up during the 1980s to ensure government decisions didn’t needlessly tie up business in red tape, the office gradually was given other things to consider, including the effect of government decisions on citizens, on the environment, and on the distribution of burdens throughout society.

Read more: Vaping is glamourised on social media, putting youth in harm's way[6]

Then in 2013 Prime Minister Tony Abbott moved it out of the Department of Finance into his own department: Prime Minister and Cabinet.

Prime Minister and Cabinet is the traffic cop: it decides what gets put forward for cabinet to decide, and when. So suddenly the office was working at the centre of government decisions, getting to view every one of the 1,800 or so things put to senior ministers to decide each year.

Seven questions shaping new decisions

For the few hundred proposals it thinks might have significant unintended impacts, the office demands an impact statement[7].

It doesn’t tell the department or authority putting forward the idea what to put in the statement. But as Lange explained, it “marks the homework”. The proposals behind any statements that aren’t good enough are harder to bring to cabinet.

Hunt’s decision on e-cigarettes wasn’t accompanied by an impact statement the first time around. Lange’s office made sure it was on the second.

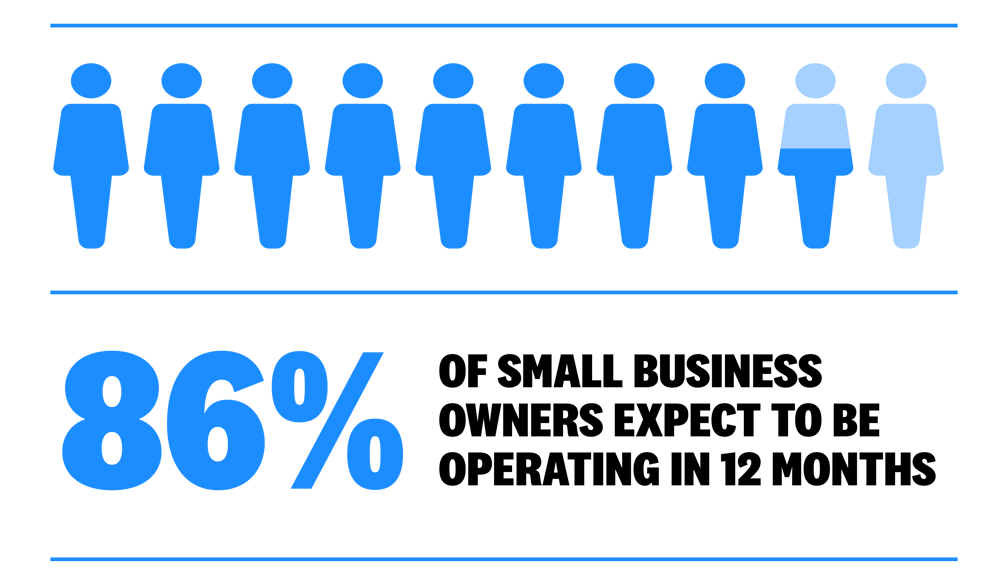

Each OBPR analysis has to address seven questions.

Office of Best Practice Regulation[8]

The first is what problem the agency is trying to solve. Maybe it’s not really a problem. Merely working that out puts what follows into focus.

The second is why government action is needed. Maybe the problem isn’t very big, or maybe it will solve itself.

The third is what options the agency is considering. The agency has to put forward at least three options, including one that isn’t a regulation. In the case of e-cigarettes, that option was a public awareness campaign.

Read more:

Vaping: As an imaging scientist I fear the deadly impact on people’s lungs[9]

Then it has to estimate the likely benefits and costs of each option, including the costs to people the option wasn’t intended to hit, such as under-the-counter retailers and people using vaping to give up smoking.

The fifth question is the range of people and organisations to be consulted (which is a way of making sure it happens). The sixth is to identify the best option from the list, which includes making no regulation whatsoever.

The seventh is the means by which the measure would be implemented and (importantly) later evaluated.

Grading government ideas, from ‘insufficient’ to ‘exemplary’

Once in, and usually after being sent back for further work, the analysis is graded on a scale from “insufficient” to “adequate” to “good practice” to “exemplary”.

Very few are graded exemplary, and very few that we know about are graded inadequate, because if such a proposal does get adopted by cabinet, the impact statement gets published along with the grade and a statement that describes its failings — a “nuclear option” Lange says can be deeply embarrassing.

All impact statements attached to proposals the government adopts get published[10] along with its OBPR rating. It is often the best opportunity the public has to read about the thinking behind the proposal.

Office of Best Practice Regulation[8]

The first is what problem the agency is trying to solve. Maybe it’s not really a problem. Merely working that out puts what follows into focus.

The second is why government action is needed. Maybe the problem isn’t very big, or maybe it will solve itself.

The third is what options the agency is considering. The agency has to put forward at least three options, including one that isn’t a regulation. In the case of e-cigarettes, that option was a public awareness campaign.

Read more:

Vaping: As an imaging scientist I fear the deadly impact on people’s lungs[9]

Then it has to estimate the likely benefits and costs of each option, including the costs to people the option wasn’t intended to hit, such as under-the-counter retailers and people using vaping to give up smoking.

The fifth question is the range of people and organisations to be consulted (which is a way of making sure it happens). The sixth is to identify the best option from the list, which includes making no regulation whatsoever.

The seventh is the means by which the measure would be implemented and (importantly) later evaluated.

Grading government ideas, from ‘insufficient’ to ‘exemplary’

Once in, and usually after being sent back for further work, the analysis is graded on a scale from “insufficient” to “adequate” to “good practice” to “exemplary”.

Very few are graded exemplary, and very few that we know about are graded inadequate, because if such a proposal does get adopted by cabinet, the impact statement gets published along with the grade and a statement that describes its failings — a “nuclear option” Lange says can be deeply embarrassing.

All impact statements attached to proposals the government adopts get published[10] along with its OBPR rating. It is often the best opportunity the public has to read about the thinking behind the proposal.

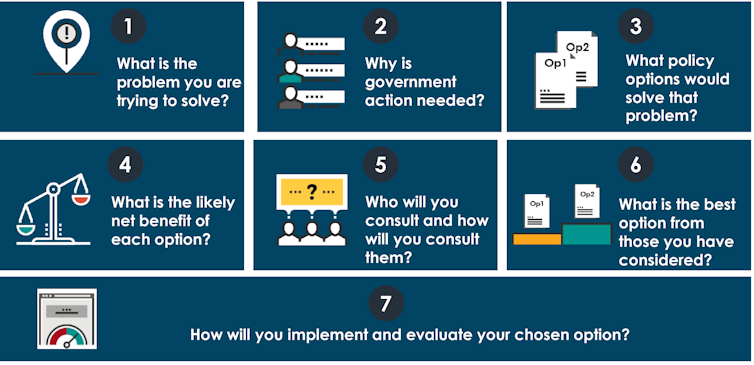

The impact statement that won the day.[11]

Tellingly, only about 80 of the hundreds of impact statements started each year get to decision makers, which means the process itself knocks out poorly thought out proposals.

But if an idea has merit, as did the ban on importing e-cigarettes without a prescription, the 180-page impact statement[12] can make all the difference.

It sets out the problem clearly, sets out a number of possible solutions and identifies the winners and losers from each, and shows how they were consulted.

It demonstrates someone in the government has thought it through clearly, and provides material for the government to use when selling its decision.

On the Office of Best Practice Regulation website[13] are hundreds of impact analyses on topics as diverse as food standards, protection for car dealers, and the redress scheme for child sexual abuse.

Vaping becomes harder on October 1

That’s why from October 1[14] it will become illegal to import without a prescription nicotine-containing e-cigarettes, and illegal to supply any liquid nicotine that isn’t in child-resistant packaging.

Behind the scenes, the government got it right.

The impact statement that won the day.[11]

Tellingly, only about 80 of the hundreds of impact statements started each year get to decision makers, which means the process itself knocks out poorly thought out proposals.

But if an idea has merit, as did the ban on importing e-cigarettes without a prescription, the 180-page impact statement[12] can make all the difference.

It sets out the problem clearly, sets out a number of possible solutions and identifies the winners and losers from each, and shows how they were consulted.

It demonstrates someone in the government has thought it through clearly, and provides material for the government to use when selling its decision.

On the Office of Best Practice Regulation website[13] are hundreds of impact analyses on topics as diverse as food standards, protection for car dealers, and the redress scheme for child sexual abuse.

Vaping becomes harder on October 1

That’s why from October 1[14] it will become illegal to import without a prescription nicotine-containing e-cigarettes, and illegal to supply any liquid nicotine that isn’t in child-resistant packaging.

Behind the scenes, the government got it right.

References

- ^ ban (www.odc.gov.au)

- ^ revolted (www.smh.com.au)

- ^ backburner (www.smh.com.au)

- ^ OBPR (obpr.pmc.gov.au)

- ^ earlier this year (esaact.org.au)

- ^ Vaping is glamourised on social media, putting youth in harm's way (theconversation.com)

- ^ impact statement (obpr.pmc.gov.au)

- ^ Office of Best Practice Regulation (obpr.pmc.gov.au)

- ^ Vaping: As an imaging scientist I fear the deadly impact on people’s lungs (theconversation.com)

- ^ published (obpr.pmc.gov.au)

- ^ The impact statement that won the day. (www.tga.gov.au)

- ^ impact statement (www.tga.gov.au)

- ^ website (obpr.pmc.gov.au)

- ^ October 1 (www.health.gov.au)

Authors: Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University