Researchers trained mice to control seemingly random bursts of dopamine in their brains, challenging theories of reward and learning

- Written by David Kleinfeld, Professor of Physics and Neurobiology, University of California San Diego

The Research Brief[1] is a short take about interesting academic work.

The big idea

My colleagues and I recently found that we were able to train mice to voluntarily increase the size and frequency of seemingly random dopamine impulses in their brains[2]. Conventional wisdom in neuroscience has held that dopamine levels change solely in response to cues from the world outside of the brain. Our new research shows that increases in dopamine can also be driven by internally mediated changes within the brain.

Dopamine is a small molecule found in the brains of mammals and is associated with feelings of reward and happiness. In 2014, my colleagues and I invented a new method to measure dopamine in real time in different parts of the brains of mice[3]. Using this new tool, my former thesis student, Conrad Foo, found that neurons in the brains of mice release large bursts of dopamine – called impulses – for no easily apparent reason[4]. This occurs at random times, but on average about once a minute.

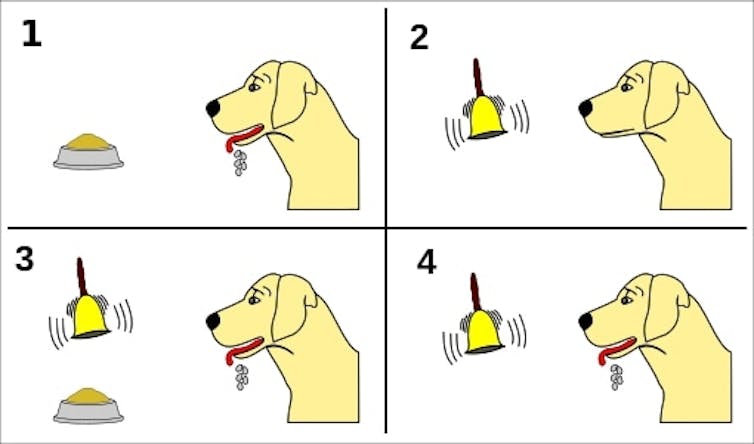

Pavlov was famously able to train his dogs to salivate at the sound of a bell, not the sight of food. Today, scientists believe that the bell sound caused a release of dopamine to predict the forthcoming reward[5]. If Pavlov’s dogs could control their cue-based dopamine responses with a little training, we wondered if our mice could control their spontaneous dopamine impulses. To test this, our team designed an experiment that rewarded mice if they increased the strength of their spontaneous dopamine impulses. The mice were able to not only increase how strong these dopamine releases were, but also how often they occurred. When we removed the possibility of a reward, the dopamine impulses returned to their original levels.

Pavlov famously showed that cues – like food or a bell – produce a response, but new mouse research shows that dopamine impulses can occur in the absence of a cue.

Maxxl²/WikimediaCommons, CC BY-SA[6][7]

Pavlov famously showed that cues – like food or a bell – produce a response, but new mouse research shows that dopamine impulses can occur in the absence of a cue.

Maxxl²/WikimediaCommons, CC BY-SA[6][7]

Why it matters

In the 1990s, neuroscientist Wolfram Schultz discovered that an animal’s brain will release dopamine if the animal expects a reward[8], not just when receiving a reward. This showed that dopamine can be produced in response to the expectation of a reward, not just the reward itself – the aforementioned modern version of Pavlov’s dog. But in both cases dopamine is produced in response to an outside cue of some sort. While there is always a small amount of random background dopamine “noise” in the brain[9], most[10] neuroscience research[11] had not considered[12] the possibility of random dopamine impulses large enough to produce changes in brain function and memory.

Our findings challenge the idea that dopamine signals are deterministic – produced only in response to a cue – and in fact challenge some fundamental theories of learning which currently have no place for large, random dopamine impulses. Researchers have long thought that dopamine enables animals to determine which cues can guide them toward a reward. Often a sequence of cues is involved – for example, an animal may be attracted to the sound of running water that only later leads to the reward of drinking.

Our observation of spontaneous bursts of dopamine – not ones that occur in response to a cue – don’t fit neatly with this framework. We suggest that large spontaneous impulses of dopamine could break these chains of events and impair an animal’s ability to connect indirect cues to rewards. The ability to actively influence these dopamine bursts could be a mechanism for mice to minimize this hypothesized problem in learning, but that remains to be seen.

What still isn’t known

My colleagues and I still need to connect the current findings with parts of the brain known to signal with dopamine[13]. In terms of behavior – such as foraging or navigating a maze in the laboratory – what is the effect of spontaneous impulses on the ability to learn? It is tempting to wonder whether spontaneous impulses could act as a false expectation of reward. It may be the case that spontaneous impulses give animals hope that a reward of some sort is “out there.” We plan to test whether there is a causal link between the spontaneous impulses of dopamine and mice venturing out to explore their surroundings. Finally, it is unknown whether the impulses help or hinder mental ability. Since the dopamine receptors in the cortex[14] are the same receptors that are overexpressed in schizophrenia[15], we wonder whether there is a connection between spontaneous impulses and mental health.

[Over 110,000 readers rely on The Conversation’s newsletter to understand the world. Sign up today[16].]

References

- ^ Research Brief (theconversation.com)

- ^ size and frequency of seemingly random dopamine impulses in their brains (doi.org)

- ^ measure dopamine in real time in different parts of the brains of mice (doi.org)

- ^ for no easily apparent reason (doi.org)

- ^ caused a release of dopamine to predict the forthcoming reward (doi.org)

- ^ Maxxl²/WikimediaCommons (commons.wikimedia.org)

- ^ CC BY-SA (creativecommons.org)

- ^ release dopamine if the animal expects a reward (doi.org)

- ^ background dopamine “noise” in the brain (doi.org)

- ^ most (doi.org)

- ^ research (doi.org)

- ^ not considered (doi.org)

- ^ known to signal with dopamine (doi.org)

- ^ dopamine receptors in the cortex (doi.org)

- ^ receptors that are overexpressed in schizophrenia (doi.org)

- ^ Sign up today (theconversation.com)