Teachers use many teaching approaches to impart knowledge. Pitting one against another harms education

- Written by Alan Reid, Professor Emeritus of Education, University of South Australia

The education debate in Australia has, for some time now, been marred by the presence of a simple binary: explicit teaching, or direct instruction, versus inquiry-based learning.

Simply put, explicit teaching[1] is a structured sequence of learning led by the teacher, who demonstrates and explains a new concept or technique, and kids practise it. Inquiry-based learning[2] is student-centred and involves the students, guided by the teacher, creating essential questions, exploring and investigating these, and sharing ideas to arrive at new understanding.

A recent article in The Weekend Australian[3] by Noel Pearson has breathed new life into this dichotomy.

It lays the blame for Australia’s declining Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) scores[4] on the fact most teachers are using inquiry-based approaches — although the evidence for this is not presented.

And it says explicit teaching is the answer.

Pearson’s argument leans on a recent Centre for Independent Studies paper[5] by Emeritus Professor John Sweller. In that paper, Sweller outlines his research on “cognitive load theory” – the idea we need to finesse a new concept until it enters our long-term memory and becomes almost second nature – to demonstrate that explicit teaching produces better learning outcomes than inquiry-based learning.

Read more: I had an idea in the 1980s and to my surprise, it changed education around the world[6]

Pearson urges teachers, politicians and policymakers to forget inquiry-based learning and adopt explicit teaching as their educational guiding star. In my view they should be very wary of doing so because the case is based on at least three serious flaws.

1. Teachers use more than one approach

First, the argument against inquiry-based learning assumes teachers use only one approach to teaching – either explicit or inquiry-based.

In my experience of teaching and working with teachers in schools, most educators move up and down a teacher-centred and student-centred continuum on a daily basis. They select, from a toolkit of teaching approaches, one that best suits the purposes of the topic or program, the context of the study, and their students’ interests and needs.

In other words, teachers sometimes employ explicit teaching and sometimes inquiry-based approaches. Indeed, they might draw on explicit teaching at a specific moment during a guided inquiry.

The idea teachers are straitjacketed to one approach is an affront to their professionalism.

2. Not all inquiry-based methods are the same

Second, the argument is based on a misguided view about what constitutes inquiry-based learning.

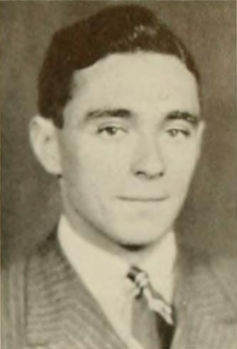

Sweller and Pearson maintain inquiry learning began six decades ago with the work of American cognitive psychologist Jerome Bruner[7] and his concept of “discovery learning” in the 1960s.

Jerome Bruner significantly contributed to learning theories, including inquiry-based learning.

Wikimedia Commons[8]

Jerome Bruner significantly contributed to learning theories, including inquiry-based learning.

Wikimedia Commons[8]

With discovery learning, instead of students being given the information to learn, they are given (or choose themselves) questions or problems and use their prior knowledge and experiences to test new understandings. Bruner argued that, as well as gaining new knowledge, students would develop crucial skills such as questioning and critical thinking, along with curiosity and a love of learning.

Pearson writes: “The great majority of Australian schools follow Bruner, even today, with only a minority of teachers and schools delivering teacher-led instruction.”

Apart from the fact he doesn’t cite any evidence to support this assertion, the implication here is that the development of inquiry-based learning stopped in the 1960s with Bruner. It didn’t.

When Bruner’s work first gained prominence it was adapted to the teaching of science[9], and then slowly spread to other areas of the curriculum. Over the next 50 years, through practice and research, a number of different models of inquiry learning have developed – each with different emphases – such as problem-based[10] and project-based inquiry[11].

More than this, inquiry-based approaches differ in such matters as purpose and method. Thus they can vary in approach such as inductive and deductive inquiry[12], and in the extent to which teachers are in control of topic choice and process. There can be strong teacher guidance (structured inquiry, controlled inquiry), or students can have greater freedom to discover and investigate (modified free inquiry).

Read more: Explainer: what is inquiry-based learning and how does it help prepare children for the real world?[13]

In other words, there is no homogenous model of inquiry-based learning. If people want to criticise inquiry-based approaches they need to be explicit about which model they are judging.

3. Flawed data used to justify the argument

The third flaw in the argument is that much of the research used to show explicit teaching produces better learning outcomes is based on data that are contaminated by the confusion about what constitutes inquiry-based learning.

Take the research published by McKinsey and Company in 2017[14], which Pearson cites as exposing the “detrimental effects of inquiry learning”. That research uses student interviews conducted by the OECD in the 2015 PISA tests to find out about the extent to which some students experienced inquiry learning in their science classes.

The questions were based on the understanding that inquiry in science involves students in practical experiments and class debates, with the teacher giving them time to explain ideas and use the scientific method. But, for all the reasons explained above, this is a very narrow view of inquiry-based learning.

Read more: Explainer: what is explicit instruction and how does it help children learn?[15]

Notwithstanding these limitations, the OECD aggregated the students’ responses and correlated them with the PISA scores in science to arrive at an index of inquiry-based instruction. This purported to show that, for many countries, there was a negative correlation[16] between inquiry-based learning and success in the science tests.

Despite the warped view of inquiry and the inadequate methodology on which the OECD report was based, once the report hit the public domain its findings were further distorted. The results based on interviews with 15-year-old students about their science teaching classes were turned into generalisations about teaching in all subjects across all year levels.

Such research tells us very little about inquiry-based learning itself. And yet it is used to demonstrate the superior outcomes produced by explicit teaching.

There’s a variety of useful teaching models — and this includes explicit instruction — which have been designed for different purposes. It is the educator’s task to select the most appropriate given the context.

Creating simplistic binaries in a field as complex and nuanced as education impoverishes the debate.

References

- ^ explicit teaching (theconversation.com)

- ^ Inquiry-based learning (theconversation.com)

- ^ The Weekend Australian (www.theaustralian.com.au)

- ^ declining Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) scores (theconversation.com)

- ^ Centre for Independent Studies paper (www.cis.org.au)

- ^ I had an idea in the 1980s and to my surprise, it changed education around the world (theconversation.com)

- ^ Jerome Bruner (en.wikipedia.org)

- ^ Wikimedia Commons (en.wikipedia.org)

- ^ adapted to the teaching of science (www.jstor.org)

- ^ problem-based (sites.nd.edu)

- ^ project-based inquiry (www.graniteschools.org)

- ^ inductive and deductive inquiry (scientificinquiryinsocialwork.pressbooks.com)

- ^ Explainer: what is inquiry-based learning and how does it help prepare children for the real world? (theconversation.com)

- ^ McKinsey and Company in 2017 (www.mckinsey.com)

- ^ Explainer: what is explicit instruction and how does it help children learn? (theconversation.com)

- ^ there was a negative correlation (www.oecd.org)